Slick lines and even slicker accuracy, the Sig P210 proves an enduring piece of Swiss engineering.

If you hear the phrase “classic IPSC,” your thoughts will probably drift to a single-stack 1911, most likely a Colt, chambered in .45 ACP. It will not have a red dot sight, it won’t have a compensator, and, if you were active back then, it probably has some funky, hand-cut checkering.

The first IPSC World Shoot was held in 1975, in Zurich. The second and third were each a year later, then the three after that at two-year intervals, until, beginning in 1983, the schedule was changed to every three years. The inaugural World Shoot was won by Ray Chapman, using a 1911 in .45. However, the championships were not won with a .45 again until 1979. In between, in Salzburg, Austria, and Salisbury, Rhodesia, they were won with a 9mm. Heresy. Worse yet were the pistols that were used. In 1977, Dave Westerhout used a Browning Hi-Power, and, in 1976, Jan Foss had used a SIG P210. The IPSC world in the late 1970s was all abuzz, and people were fairly concerned. Not only had 9mms been used to win, but one of them had even been a single-stack!

Origin Of The Sig 210

The P210 began life before WWII, when the Swiss determined that the M-1900 Lugers they had been using were perhaps not the best military sidearm to be had. In 1900, the Luger was cutting edge, and the .30 Luger cartridge it was chambered in was a real hot number. But, by the late 1920s, it was clearly not up to snuff. So, the Swiss Army embarked on a replacement plan. They liked the technical designs of Charles Petter and licensed the principles of his M1935, which had been adopted by the French. The Swiss wisely adopted the idea, but not the actual French pistol, itself an under-powered little beast. The irony of a Swiss designer developing a French pistol that the Swiss then had to pay to license is a head-scratching one. But I guess Charles wasn’t the first one to find a warmer reception away from home.

Advancing plans for the new gun was slowed with the start of WWII, since the Swiss had bigger problems than replacing useable, albeit less than optimum, sidearms. But the advancement didn’t entirely stop, and, once the war was over, the Swiss proceeded to finish testing and adopting their new pistol. In Swiss service it was known as the Pistole 49, in 9mm Parabellum, .30 Luger, and .22LR. The first and last are obvious choices; the Swiss wanted the 9mm for its greater performance and common availability, while the rimfire made for an inexpensive practice pistol. But 7.65X21? Remember, in the Swiss defense system, every citizen is a member of the defense. Once through basic training, everyone goes home with a rifle and ammo and, when they retire, they generally retain the individual weapons. A family may have four or five generations of smallarms locked in the home armory. When adopted in 1949, the Swiss had a half-century of the .30 Luger ammunition existing as the established standard, and there was probably a large amount of it on hand. Since the difference was a new barrel and recoil spring, why not make it in 7.65?

P210 has been updated.

The P210 is a single-stack, all-steel 9mm, and the aspects of the Petter design that the Swiss adopted were worth it. The military pistols were clearly products of their time and place. The grips were wood or plastic, and there was a half-rectangle steel bracket on the left side of the frame, with the grip on that side cut away for clearance. Given that the lanyard loop, safety, and slide stop were all on the left side, convenient for right-handed shooters, I have to conclude that no one in the Swiss Confederation is born left-handed. If there was ever a lanyard clipped to the loop, I’m not sure you could comfortably shoot the P210 left-handed.

Below the lanyard loop was the heel clip, the typical European method of retaining magazines. I have long wondered what the horror or fear of magazines falling free is, such that it grips European firearms designers (or buyers) with the need for such a three-handed design. It also had a magazine disconnector, so, when the magazine was out, it was a steel club. The Swiss Army replaced the P210 with the SIG P220, in 1975, but production of the P210 continued until 2005. I can easily imagine that the P210/Pistole 49 continued to be made because people still wanted it.

P210-9 Redesign

One big reason for this is the gun’s accuracy. However, used P210s couldn’t satisfy the market for highly accurate, beautifully machined pistols, so, SIG Sauer undertook a slight redesign and began making them again. The one we have here is the P210-9, the modern version of the P210, and the improvements have all been for the good.

First up, one aspect of the original that was not all that satisfactory was the shape of the tang. Designed back when handguns were still being fired one-handed, the tang worked fine for a low-thumb, one-handed hold. But the moment you tried to fire it with anything like a modern grip, you would pay the price. I am particularly disadvantaged in this regard, and the original P210, along with a select few other pistols, is one I simply cannot shoot without assistance, as in I have to wear gloves or prepare my hand with duct tape before shooting. If I do not, I will bleed. Not an exaggeration, shooting a P210 can have me bleeding like a stuck pig, in less than a box of ammo. With a pristine P210 going for more than two grand, you can imagine the looks of horror that would create from the owner who so rashly loaned me one. The P210-9 variant, imported by the SIG Sauer folks in New Hampshire, has a re-designed tang. It is now in the same league as a beavertail safety on a custom 1911 and protects the hand from the hammer. I was able to spend a full day shooting the new 210 without fear of bleeding.

The new P210 has a proper, American-style magazine catch. Nestled right behind the trigger guard, it allows the magazine to drop free when pushed. And, yes, the magazine does drop free, there being no magazine disconnector in the new pistol.

The grips, since they do not have to accommodate a lanyard loop, are symmetrical, but not interchangeable. They are made of oiled hardwood, and the fit is such that you can remove the grip screw (a torx-headed screw, by the way) and still have little or no fear of losing the grips. In fact, if you aren’t careful, you risk damaging the grips, trying to take them off the frame.

The grip shape, under the grips, makes no concession to hand shape. The front strap is proportioned for your hand, but the rest of the frame is simply a place to hold the magazine. The grips are expected to make the grip fit your hand. That’s a proper bit of engineering.

The thumb safety is not what people will expect. Instead of being a lever at the back of the frame, like the 1911, it is a lever in front of the grip. Your thumb can reach it, but, if you haven’t practiced with it, it will be a bit awkward. On the -9, the safety is fitted so as to be easy to move back and forth (or up and down, if you will), and it is only the thickness of the grip panel that makes it a bit of a reach. If you really wanted to use the 210-9 as a competition gun and had to have ready access to the safety, you could carve on the grip to make that possible. You might want to consider doing so to a spare grip set, so you will have the original grips un-molested for the future.

The slide stop is big, hard to miss, and, for me, a bit in the way. My thumb is long enough to reach it in my firing grip, and the slide stop is big enough to bump, if I’m not careful. Of course, on reloads, being big and hard to miss is good, because dropping the slide via the “slingshot” method isn’t easy.

The slide on the -9 has fixed sights, with both the front and rear held in transverse dovetails. An interesting detail, laid out in the owner’s manual, is that both the front and rear come in a variety of sizes (denoted with numerical markings), so that, if a particular pistol is off the sights, the blades can be swapped, mixed, and matched until it is dead on. The brother P210 that SIG is importing is the P210 Legend Target, which has an adjustable rear sight.

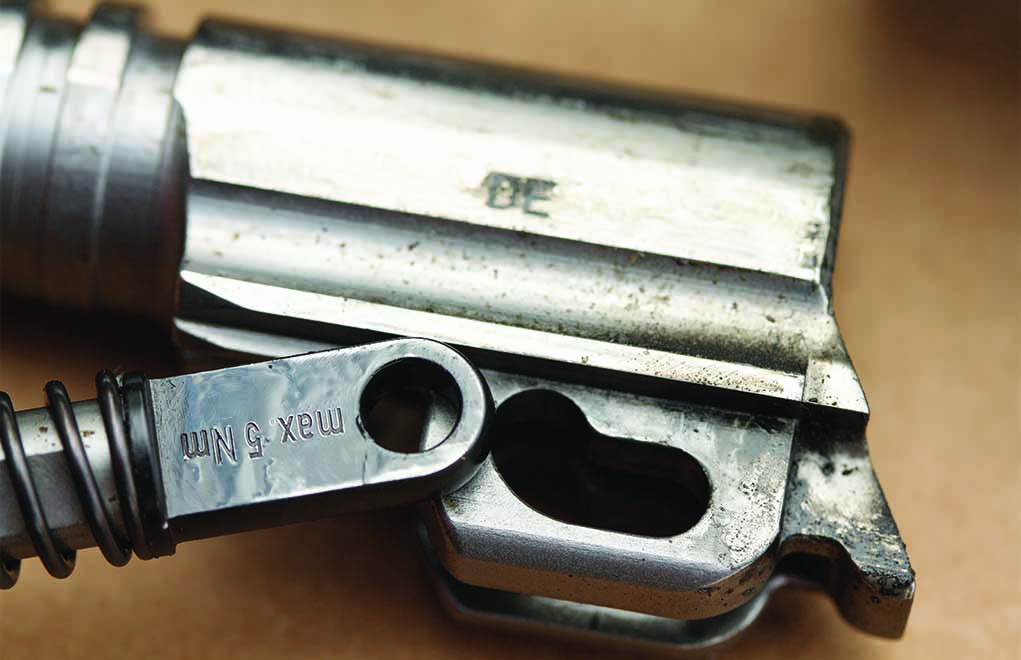

The 210-9 lacks a barrel bushing; the Swiss are clearly comfortable with the idea of precision machining and keeping the tolerances close enough so that they can produce an accurate pistol without the need of a bushing. Disassembly is easy. Unload and then ease the slide back a quarter-inch or so. Press the slide stop out to the left and, once it’s clear, you can slide the upper assembly off the frame. The recoil spring is a captured unit, and it has an interesting attention to detail—the head of the recoil spring assembly has stamped on it the torque limits of the rod assembly. The “5 Nm” is newton-metres, a measure of torque, which translates to just over 44 pound-inches. In other words, it’s tightened down about the same as a scope mount screw and meant to stay there.

The recoil spring guide rod has a hole in the end, and it is part of what the slide stop shaft passes through. The barrel lugs are like the cam slot of other pistols that you may be more familiar with (no link here), but with a twist. The lugs are made as a pair and widely-spaced (as handgun parts go), so they provide a wide base for the barrel on the slide stop. I have to think that has something to do with the accuracy. The barrel locks into the slide the same way as every other Browning-derived pistol does, with lugs on the barrel engaging slots in the slide.

One aspect of the P210 is obviously contrary to the way things are now done. The rails on the frame are on the inside, while the rails on the slide are on its outside. The idea was to reduce wear and retain accuracy. It also increased potential accuracy, but not due to the inside-outside design. A secondary aspect of the design is that the contact between the slide and rails extends a lot further on the 210 than it does on other pistol designs. Think of it like sight radius: the further apart the sights are, the easier it is to notice aiming errors. On rail contact, the further apart the front and back contact points are, the more aligned the slide and frame will be. I love the 1911, but the P210 has twice the rail length as the Browning. That increases repeatability, which improves accuracy.

it only blocks the trigger bar.

One of the Petter details included was a hammer/sear assembly that went into or came out of the frame as one piece. No separate hammers, sears, etc. Now, I see this mostly as an organizational advantage. If you are the armorer of a police force or military unit, you can have a set of pistols that are issued to the troops, and you can have, in the armory, a selection of assembled, tested, and sealed units. If someone has a problem or a pistol shows wear, it is perhaps a minute to swap out the old, install a new, and send the owner on their way. No downtime for the officer or pistol, and now you, the armorer, can work on the recalcitrant assembly without someone hanging over your shoulder or having to deal with the paperwork of checking in the busted pistol, issuing a new one, and repeating all that when the repair is done.

But for that, it is a cracking good idea, and, had I a hat, off it would be to the Swiss for having adopted it. For us, however, it doesn’t matter much. The trigger assembly and its removal isn’t mentioned in the owner’s manual (SIG would be very happy if you just left it alone), and unlike the old design, where the assembly was held in with a pin, the -9 has the assembly locked in place by means of a screw up through the tang. Again, it’s a torx, and there’s no need to remove it. If you do, you’re on your own.

The slide and frame are machined from steel billets, given a satin matte surface, and then treated to the SIG Nitron finish. The trigger, safety, hammer, and slide stop are left bright, but not polished to a mirror finish.

The interesting thing—as if all the above was of no interest—is the trigger. We are used to light and crisp, or “combat” and crisp, and the Swiss clearly have a different idea about these things. The trigger is light, but it has take-up, and then it has travel, which, if you aren’t slowly pressing, feeling as you go, feels the same. It’s almost as if it were the world’s shortest double-action PPC trigger. I first felt a trigger like this when test-firing an Stg90, the Swiss military rifle in 5.56. That trigger was light, but with enough travel that you know you’re pulling the trigger. On the -9, this took a bit of dry-firing to get used to, as I found transitioning from “regular” triggers to the P210 trigger to be too much in one range session. When I tried, I ended up nearly perforating my chronograph a few times, as I, too, up the slack on the P210 trigger and shot sooner than anticipated.

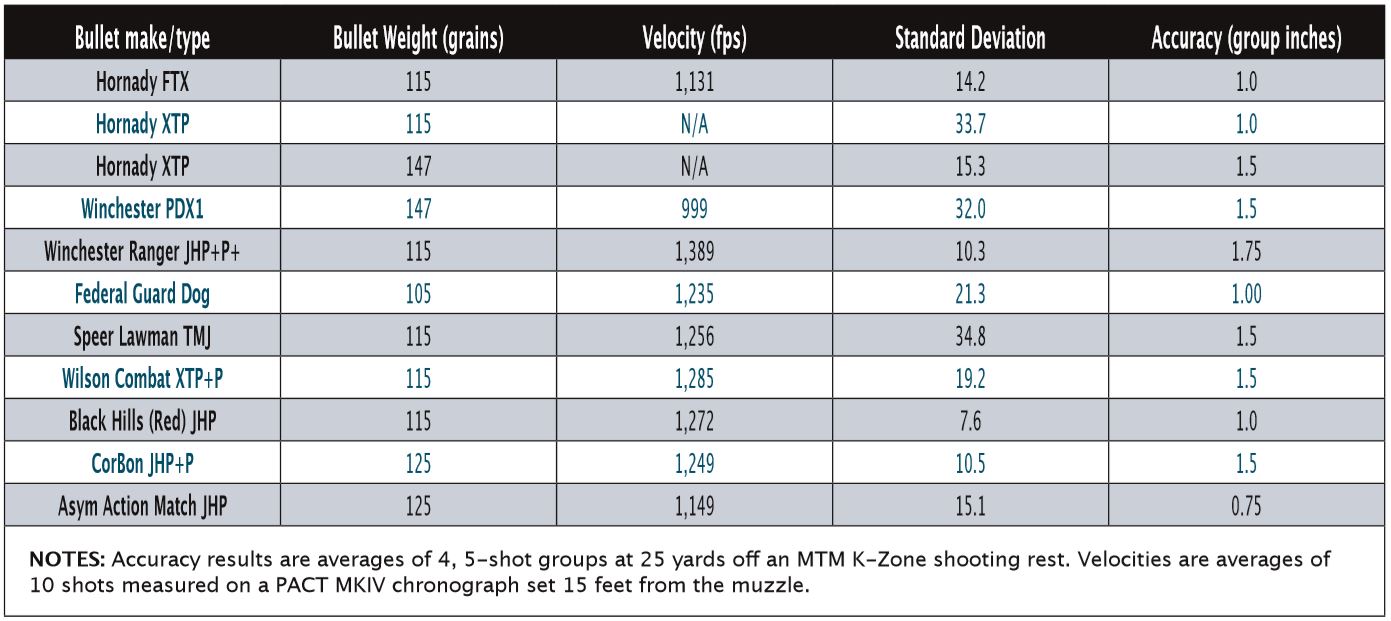

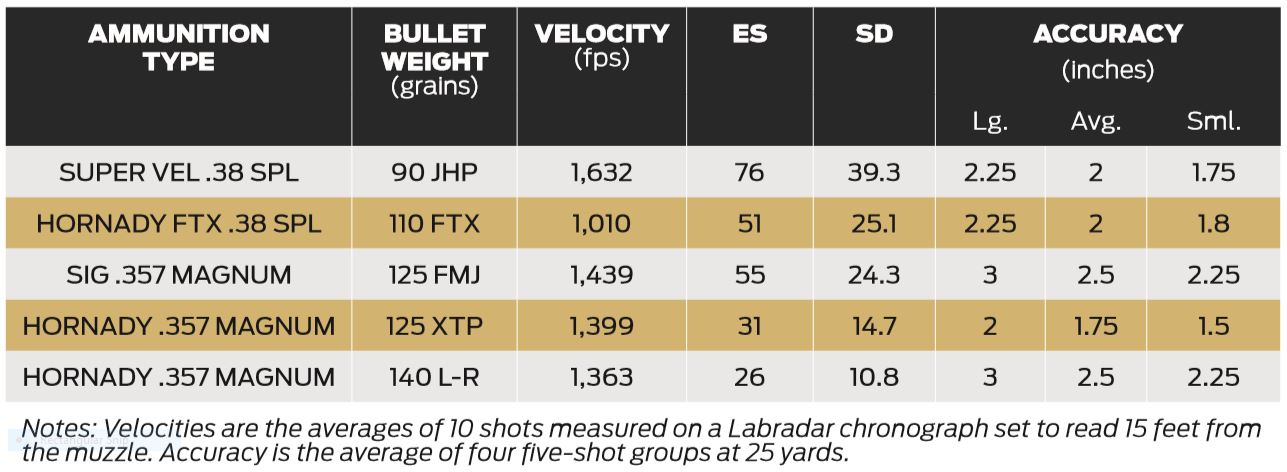

But, I’m glad I persisted. I’ve been mentioning accuracy all along, and the P210 is a scary-accurate kind of handgun, a one-inch-groups-at-25-yards kind of handgun. And, unlike some pistols, the P210 did not get picky about what it liked to shoot. Yes, it shot better with some, but the differences were almost immeasurable. I mean, if one ammo groups a quarter-inch larger or smaller than another, can we really say the pistol “prefers” it? That level of accuracy, and that small of a difference, requires several things. First, a Ransom rest, of which mine is on loan and for which I do not have a set of P210 holders. Second, you need a pile of ammo, all of it with the potential for gilt-edged accuracy. And you need the the time to shoot groups, and I mean statistically significant groups, not your basic five-shot groups and not even four consecutive five-shot groups, but real number-crunching efforts like five ten-shot groups with each brand and bullet-weight ammo. This is the kind of shooting that’s a full-time job by itself.

Explore Related SIG Sauer Articles:

- Discover the Best Sig Sauer Concealed Carry Options for Every Lifestyle

- Best SIG P365 Accessories – Must-Have Add-Ons

- A Detailed Look at SIG 516 Specs

- SIG P6 Specs – Features That Made It a West German Icon

- SIG M17 Test – Performance and Precision Under Fire

- Kimber Micro vs SIG P938 – Compact Options for Everyday Carry

On The Range With the P210

So, once I had done the usual group-testing, I amused myself by plinking—on the 100-yard range. Pick an object, something safe to shoot at. Aim, press. OK, it got hit, now what? Pick something smaller. Same results. This handgun is almost scary to shoot, and a little intimidating to own. Imagine owning a handgun and knowing that, if you shoot it at the gun club, everyone knows that any miss, any shot that drops a point is your fault and not the gun’s. A P210 would be brilliant for shooting in a PPC league. Do some experimental reloading, find a load that shoots small groups (won’t be too difficult), hits to the sights, and prepare to have your average rise.

One small obstacle might be magazines. With an MSRP of $72 each, you will want to take really good care of them and not let them get stepped on during the winter indoor leagues and tight range spaces. You certainly don’t want to drop them on concrete with the same abandon you’d jettison a $15 1911 magazine. But, if you can see your way to four or five of them, you’ll have a tack-driving 9mm to shoot.

Oh, and those early days of IPSC? After Ross Seyfried won the World Shoot in 1981 with a very plain, by today’s standards, .45 1911, the world changed. Starting with Robbie Leatham, in 1983, the .38 Super was king of the hill. Then, in 1990, the 9X21 gained glory, and that’s the way it has been. There will not be another World Shoot champion using a .45 ACP pistol until 2014. Maybe. Then, the new Single-Stack/Cassic Division will be contested, and the .45 has a chance again—unless someone wants to give it a try with a P210. This one is certainly up to it.

Sig P201 Specs:

Type: Hammer-fired semiauto

Caliber: 9mm Parabellum

Capacity: 8+1

Barrel: 4.7”

Overall length: 8.5”

Width: 1.3“

Height: 5.6”

Weight: 37.4 oz

Finish: Nitron

Grips: hardwood wrap-around

Sights: steel patridge

Trigger: single action

Price: $2,199

Manufacturer: Sig Sauer

For more information on the Sig P210, please visit sigsauer.com.

Editor's Note: This article is an excerpt from the Gun Digest 2013, 67th Edition

![Best Concealed Carry Guns In 2025 [Field Tested] Wilson Combat EDC X9S 1](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Wilson-Combat-EDC-X9S-1-324x160.jpg)

![Best 9mm Carbine: Affordable PCCs [Tested] Ruger Carbine Shooting](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Ruger-Carbine-Shooting-100x70.jpg)

![Best AR-15: Top Options Available Today [Field Tested] Harrington and Richardson PSA XM177E2 feature](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Harrington-and-Richardson-PSA-XM177E2-feature-100x70.jpg)