How to buy a suppressor.

What You Need To Know To Buy A Suppressor:

- Two basic types: baffle stack and monocore.

- They come user serviceable and sealed.

- Five types of sealed: Cap-welded, Tack-welded, Fully Welded Stack, Fully Welded with no tube, monocore.

- Federally legal they suppressors are not legal in some state and municipalities.

- Background check is necessary.

- Form 4 transfer approval application must be filled out.

- FBI fingerprint cards and photo are also required.

- $200 tax payment.

- Form 4473 is final form, fill out upon receiving the suppressor.

- Trusts are used to allow multiple people possession of a suppressor.

Simply put, a suppressor is a tube with a series of partitions inside that trap the expanding gases and slow their release into the air. This reduces the pressure wave, and thus the noise, the firearm creates.

The full technical explanation involves physics, metallurgy, heat transfer, the chaotic movement of gases under pressure, and we’ll skip that.

Suppressor Design And Construction

Making a suppressor is both easy and difficult. It is easy, in that pretty much anything you put over the end of the muzzle will dampen noise. (Which can, in some instances and designs, be against the law without proper paperwork.) It is difficult in that what you use to dampen noise can degrade accuracy, cause difficulties aiming, and can be inconvenient, messy and just plain ugly.

Suppressor designers and manufacturers work hard to make suppressors easy, convenient, good-looking, not harmful to (actually increasing) accuracy, and all this while significantly reducing noise.

The basic designs of suppressors fall into two camps, and each is either sealed or user-serviceable. User-serviceable is the technical term for “take it apart and clean it.” The two camps are baffle stack and monocore.

Baffle Stack

The baffle stack design entails a tube, and inside the tube the manufacturer places a stack of relatively cone-shaped baffles. Back in the early days, there were two versions, the “K” baffle and the “M” baffle. Today, we have more than two, they all work, and the details matter only to those who obsess over fractions of a dB in on-the-range testing. The baffles are machined to have space between them. The spaces they create are the volume into which the gases will expand. The first of these is called the “expansion chamber.”

The baffles can have various shapes, as seen in cross-section, and they can also have holes drilled through them to create turbulence in the gas flow. Turbulence increases efficiency and makes a suppressor quieter, although some argue just how much it matters.

The baffles must be kept in place, so they are machined for a snug or tight fit in the tube. The tube is sealed with front and rear caps, trapping the baffle stack inside. The rear cap also contains the mount design, either direct-thread or QD.

On a rimfire or pistol-caliber suppressor, the front and rear caps are threaded so you can take the suppressor apart and clean it. If you do not, it will collect powder residue, lube and bullet material, which hardens into an impressive layer. This can build up until the suppressor is only a heavy tube with minimal clearance for the bullet, and no effective baffles left, the baffles now buried under the gunk.

Rifle-caliber suppressors are self-cleaning, and as a result they are not often user-serviceable. They do not need to be, unless the centerfire rifle you shoot uses cast lead bullets. Then, you’d better have a cleanable suppressor on it.

Sealed Suppressor Welding

A sealed unit will have, at the very least, the front and end caps welded to the tube. Generally speaking, more welding creates a more durable a suppressor. There are five levels.

Cap-welded

Here, the front and rear caps are welded on and the baffles are simply pressed into the tube and trapped in place. While the baffles are tightly packed, they are not attached to the tube.

Tack-welded

On these (usually older designs), the baffles are stacked outside of the tube, and the edges welded at two or three points on their perimeters, creating a rigid assembly. The welds are then filed/ground flush, and the baffle stack is pressed into the tube, where the caps then are welded on.

Alternately, the tube can be drilled at spots along its length where the flanges of the baffles would rest, the baffles inserted, and each hole weld-filled with the baffles in place. As a result, each baffle has two or three welded attachments to the tube, through where the holes had been.

Fully Welded Stack

Here, the rim of each baffle is welded its full circumference to the next baffle in the stack. The assembly is then ground or lathe-turned to be round again, and then pressed into the tube, where it can be welded in place or the caps welded on, or both. Also, each can be welded in turn into the tube, but this is a lot more difficult.

Fully Welded, No Tube

This is the process used by Sig. They fabricate the baffles such that they have external, cylindrical skirts. The baffles are then fully welded into a stack, and the skirts form the tube that the baffle stack would otherwise be shoved into. This is a process that requires a great deal of precise equipment, but the end result is a suppressor with greater internal volume and less weight, since it does not use both a baffle stack and an external tube.

Monocore

Here, instead of the baffle stack being composed of a series of cone-shaped parts, it starts as a solid cylinder of the baffle material. Then, through the magic of multi-axis CNC machining, the cylinder has gaps, holes, and baffles machined out of the bar stock of metal. This is then inserted into a tube. The big advantage here is that the monocore can be created in shapes that no baffle stack of cones could ever duplicate.

The monocore tends to be a bit heavier than an equal diameter and length baffle stack, but that can be offset by the choice of tube materials and thickness.

The big advantages are that the extra contours of the monocore can make for a quieter suppressor, and it is easier to make a rifle-caliber suppressor that can be disassembled and cleaned. As a result you can use a monocore suppressor as a multi-caliber compromise, since it is a lot easier to take apart and clean.

There is one other design detail of the monocore that can matter, or not. It is relatively easy to not only make a monocore suppressor that can be taken apart, but also incorporate into the design an external tube that does not have threads on it. The plain tube is the part that has the manufactures name, model number and serial number on it. If, in disassembly or cleaning, you were to damage the threads (easy to do if you have neglected it, and it is carbon-welded into a single part), the threaded parts, the front cap, rear cap or monocore can easily be replaced. The tube, lacking threads, is extremely unlikely to be damaged by such heavy-handed treatment, and thus you do not have the headache of having it repaired.

What’s The Most Effective Suppressor Baffle Design?

Which method a manufacturer uses depends in part on when they began making suppressors, how much they are willing to invest in capital equipment, and what the caliber and use demands. A maker that has been in business for a number of years, with familiar equipment capable of making solid, dependable old-style suppressors, may be reluctant (and understandably so) to invest in a lot of new equipment that will make suppressors only a little bit better than what they make already.

As the buyer, you can decide what type you want, with the understanding that the more welding there is, the more it will cost. If you do not need a fully-welded suppressor, then don’t buy one. A hunter, for example, really doesn’t have a pressing need for a full-auto-rated suppressor. Buying one will entail higher cost and greater weight.

You will be advised by those who claim to be experts that money spent on any suppressor that isn’t full-auto-rated, or adopted by SoCom or SEALs or some other black-bag group, is money wasted. You must, simply must, buy the most rugged, extreme-use, manliest suppressor, or you are a poseur, dilettante, or not serious. Ignore them.

This is your decision, your purchase, and you will be the one using it in the future. Buy what fits your needs, your wallet, and your self-image. If that requires weight, exotic materials and a military provenance, go for it. If not, go for it anyway, and have fun.

How To Buy One

The popularity of suppressors has caused a growth in the number of outlets where you can buy them. Gun shops that were “01 dealers” only had to add an SOT to their license wall, and then they could begin selling suppressors. As a measure of their popularity, you can now find suppressors in the Brownells catalog.

Buying is easy. Frustrating because of the wait and the paperwork, but easy.

First, do you have the money? Suppressors aren’t cheap, even an “inexpensive” .22LR suppressor can cost more than the rifle or handgun you are putting it on. And, you have to have a suppressor-ready firearm. Do you have one of those? No? Then can you afford to also buy a gun onto which you can put the suppressor?

Second, do you live in a state that allows them? In a lot of areas of the legal landscape, the federal government has been more than happy to trump state law. There was that whole 55 mph on the freeways thing, a while ago. Oh, a state could tell the federal government, “We don’t think 55 is right, we’re going to post a higher limit.” The federal response was simple, “OK, but you aren’t getting a dime of federal money for road building, maintenance, and anything else we can think of, relating to roads, while you are over 55.”

Federal law has a path to buying a suppressor, but they won’t insist on it over the objections of a given state or local jurisdiction. So, if your state doesn’t permit it, the Feds won’t help you. “Application denied, money refunded.”

So, the first two hurdles? Money and state.

Next is your own background. Have you bought a gun recently from an FFL holder? Or do you hold a CPL? If so, cool, you have already gone through the kind of background check the ATF will do on you for your suppressor application. If you passed those, you’ll pass the next. If you haven’t, then you have to do some deep thinking about your past behavior. Be honest with yourself. Ever been arrested? Ever skipped on child support payments? DUI? Have you ever had any kind of a run-in with the law? Do you have an ex who bears you no good will? Because the ATF will check, and if they find you have some sort of disqualifying problem, and you haven’t gotten the situation cleared up, then your application will be cheerfully denied.

So, have a clean record and you’re good. If you don’t have a clean record, your problems need to be resolved before you apply.

Next, find a dealer. This isn’t as hard as it used to be, as the manufacturer of the suppressor you are interested in will be more than happy to tell you the dealers in your area, and which of them might even carry their product in inventory.

With a dealer or dealers in mind, go there and see what they have, or what they can order. You have this book, you have magazine articles, hopefully you’ve done your research.

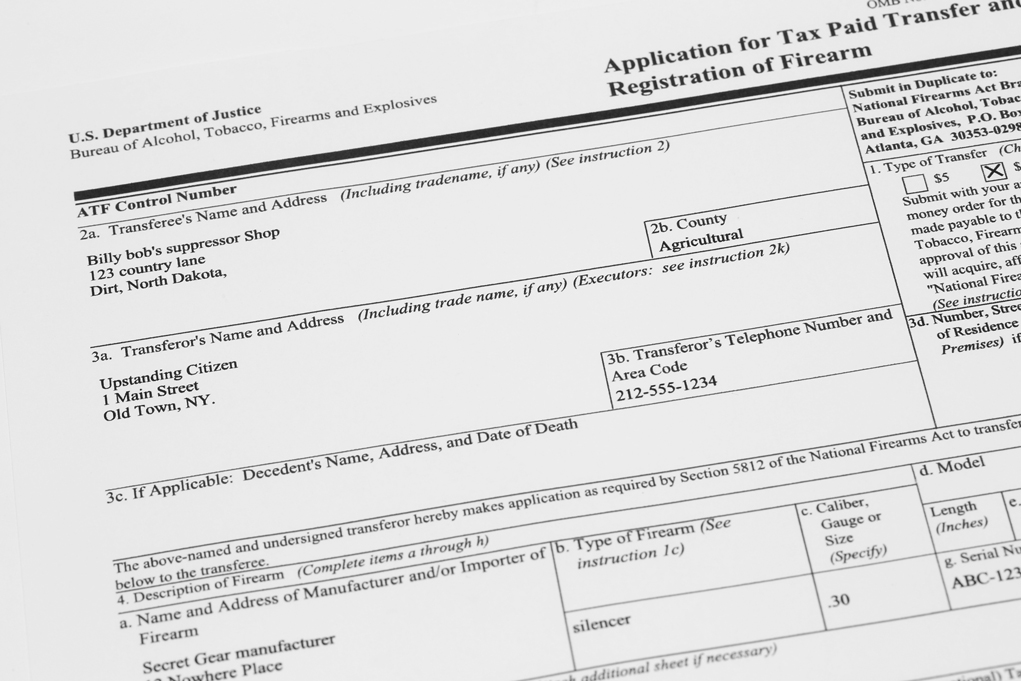

Shop, discuss, work out a price, and pay for it. Once paid for, it is yours, but you don’t get to take it home. It may not even be there in the store. This is where the patience comes in. You and your dealer will fill out the form, in this instance a Form 4, a transfer approval application.

This is different from the Brady check you went through when you bought a gun last year. There, they were simply verifying that you weren’t a prohibited person. Once that was established, the dealer could sell you whatever gun he had on hand, or order one.

The Form 4 is an application to transfer a particular item to you, at this time. That’s why the form has your name, the dealer’s name, the model and serial number, and manufacturer’s name of the suppressor on the form. The form approves the transfer of this suppressor, from this dealer, to this person, on the date approved, and not a minute before. And it is what you will have to go through each time you buy another suppressor.

Once the Form 4 is filled out, in duplicate, take it to your CLEO along with the FBI fingerprint cards. And again, they want specific cards. The ATF does not want to see your local police department’s fingerprint cards, or the state police, or anyone else’s. They want the FBI cards they specify. Get fingerprinted, get the CLEO sign-off, wash your hands, write a check for $200 and, wait, there’s one more step – get photographed. You’ll need a pair of passport-quality photos, so comb your hair, put on a smile and get your pics. Then you can send it all, in one envelope, to the address on the form.

Oh, and be a smart guy and make sure the check will clear the bank. If the check does not clear, your transfer is denied, and you won’t find out until the paperwork is returned. Don’t send cash, don’t send anything but approved funds. Now, if you want to make sure that there is no question, sending the ATF a U.S. Postal Service money order will likely work. I mean, a USPS MO is as good as cash. But they do accept personal checks, and that is easy.

Then you wait. And wait. It takes as long as it takes, and phoning to “see how things are going” simply delays the process.

Now, there was an electronic form that was used for a while, and may well be back by the time this hits print. This sped things up quite a bit, as the examiner didn’t have to wade through piles of forms, all arriving in the mail in one big bag, to do the work. However, as with so many things, some smart-alec (stronger words were used at the time) screwed it up for everyone else. What I have heard from those on the inside was this: some too-clever outside programmer figured out how to “jump the line” and get their own electronic transfer applications moved up to the head of the line.

Once this was discovered, the ATF figured, and rightly, that if the system could be “gamed” that way then they had to close it down until it could be made secure. So, we went back to the paper system. I had a bunch of electronic transfers in-process at the time, and when the ATF decided they couldn’t continue, they voided all of them (mine and everyone else’s) and told us to go back to paper.

Thanks to whoever was responsible for that.

OK, you’ve been patient, you’ve been approved, and your form has come back stamped and ready to be used. There’s still one more form you have to fill out, the 4473.

You see, as defined by law, a suppressor is a firearm, which means it requires the 4473. Your dealer is familiar with this, and will mark it as “other” when you get to the box on the form. (Hey, it isn’t a rifle or shotgun, it isn’t a pistol or revolver, what else can you call it?) You finally get to take your new toy home. Make sure you take care of it, keep it locked up and know where it is. It would be bad enough to explain to the local police and insurance company that you “don’t know where” your deer rifle is, but a suppressor? That one brings in the Feds.

Trust

No, not the feeling you get when you see your grandmother (I hope you can trust granny), but a legal trust. A legal trust can take a number of different forms, and these forms have variations from state to state. But the essence of a trust is that it is a legal entity that can possess property or items of value, and those items are not considered to be possessed by the individuals who hold the trust.

The whole idea of a trust, and why it even exists, is a matter of historical and philosophical legal arcana. But they exist, and for our situation they can be very useful tools.

You see, your Form 4 must have a signature from the “Chief Law Enforcement Officer” of your area. We’ve covered this in chapter three, Myths, but it bears repeating: you form a trust because the CLEO won’t sign. If you do form a trust, it would be prudent for you (and a good idea for the rest of us) to make sure no one who has access to your suppressors might be in a prohibited category. Prudent for you because handing a suppressor to a prohibited person is a crime, and good for us because if the trusts are abused, they will go away.

Get More Suppressor Info:

- Best AR-15 Suppressor Options For A Quiet Advantage

- Handgun Gear: Best 9mm Suppressor Choices

- Best .22 Suppressor Choices To Mute Your Plinker

- Choosing A Flash Suppressor, Muzzle Brake And Compensator

It is one thing to be at the range on a beautiful day and, after handing your daughter’s boyfriend your suppressor-equipped firearm to plink with, find out later he is considered under the law a “prohibited person.” It is something else to have had him named on the trust papers as having access to the suppressor, and all the other toys, for who knows how long. The first can be laid at the feet of inadvertence, and “I didn’t’ know at the time.” But to put someone on the trust, you’d be smart to make sure you know what you need to know.

There’s also the matter of taxes. A trust pays a tax on the transfer, just like a person does. If the trust has to be dissolved, then the transfers out of the trust will also be taxed to the new owner or owners of the suppressors. If, on the other hand you own them personally, your inheritor may not have to pay the transfer tax. As with so many things, it depends.

And, in a curious twist, it wasn’t that long ago that the ATF themselves suggested that the CLEO requirement be done away with. After all, with instant, digital background checks now the norm, and readily available to any law enforcement agency, and since the ATF was doing it themselves, what did they need the local LE to be doing it for?

That was entirely too rational a suggestion for the administration in place at the time, and it wasn’t but a couple of years after that the “suggestion” came floating down from the administration that the CLEO sign-off be added to trusts.

When someone tells you that voting for the “lesser of two evils” is still voting for evil, remind them that we probably wouldn’t be dealing with nonsense like this, were it a Republican administration. Sure, we’d be dealing with different bone-headed ideas, but they’d be less hazardous, and easier to quash.

Trust extras

Let’s assume you own a suppressor or a bunch of them and you finally run out of luck. What happens to your suppressors? Well, if you have them covered in your will, your executor can handle things, but they won’t like you for it. You see, while the inheritor of your suppressors waits on their paperwork, the items in question are in legal limbo. You own them, but you are dead. The new owner doesn’t have approval to own them. Where do they stay? In the bank safe deposit box? In the desk drawer of your attorney who is handling the will? It is entirely possible that your state law will require them to be handed over to the custody of the local police until the new paperwork is approved.

And there is also the matter of publicity. You see, a will is good, but it will not prevent you from going through probate. And when the court gets involved, and your will goes through probate, it all becomes a matter of public record. As a friend of mine pointed out, when Bob Hope died, and his property was disposed of according to his will, it all became a matter of public record. But, when Bing Crosby died, he had formed a trust (no idea if there were suppressors involved) and no one outside of the inheritors know what was involved.

A trust solves all that uncertainty. You die, and the other named trust officers still have access, and the trust still owns the items.

And if you have set up a trust to cover the disposition of your property, there is no probate, there is no public record, and no one with the search software can simply troll court records and find out what you owned and to whom you left it.

Even if don’t form a trust to transfer suppressors, get yourself a trust to cover your property disposition instead of just a will.

Editor’s Note: This article is an excerpt from The Suppressor Handbook by Patrick Sweeney.

Next Step: Get your FREE Printable Target Pack

Enhance your shooting precision with our 62 MOA Targets, perfect for rifles and handguns. Crafted in collaboration with Storm Tactical for accuracy and versatility.

Subscribe to the Gun Digest email newsletter and get your downloadable target pack sent straight to your inbox. Stay updated with the latest firearms info in the industry.

![Best Concealed Carry Guns In 2026 [Field Tested] Wilson Combat EDC X9S 1](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Wilson-Combat-EDC-X9S-1-324x160.jpg)

![Best 9mm Carbine: Affordable PCCs [Tested] Ruger Carbine Shooting](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Ruger-Carbine-Shooting-100x70.jpg)

![Best AR-15: Top Options Available Today [Field Tested] Harrington and Richardson PSA XM177E2 feature](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Harrington-and-Richardson-PSA-XM177E2-feature-100x70.jpg)

These things cost $500 and up and with the $200 tax stamp and dealer fees you are easily pushing $750 or more. Ridiculous, you can make one for $50 and the Feds don’t need to know you have it and if you live in an oppressive state that doesn’t allow its’ citizens to have one you can get around that also.

Can you tell me how much does the Suppressor cost for the New Ez,Equalizer cost.??