The cartridge case is the most controllable element in precision reloading. Here are the facets to turning out optimized brass.

How You Can Perfect Your Brass:

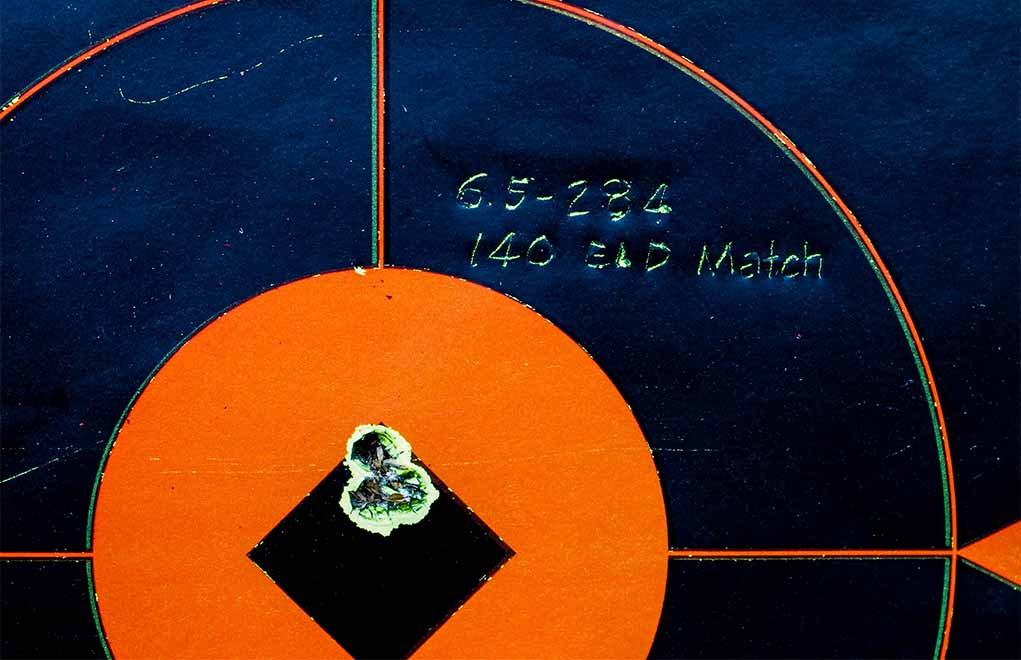

Precision reloading is a process in which the results are directly proportional to the efforts you put in. If you’re careful in the preparation of your cases, taking as many precautions as possible to keep things uniform, you will—or, at least you should—see the benefits on the target.

I look at it as if it were a cooking recipe: If you start with poor ingredients, even the best technique in the kitchen won’t save your dish. Likewise, if you’re trying to cook over an open fire when the dish calls for a specific controlled temperature, odds are, it just won’t come out right.

Case Prep

As reloaders, the preparation of our cases is where we have the most control. Our projectiles can be sorted (according to weight, length of base to ogive, etc.), and our brand and type of both primer and powder can be experimented with. No; we can’t control their performance; we can only work around what they deliver. The cases, however, although they come in a particular shape, can be modified or trued to give the most uniform results.

Quite obviously, starting with the best cases you can will be the most advantageous, but no matter what you start with, steps can be taken to make it the best possible.

If you’re using fired brass, a good visual inspection should be the first step in the process. If there are any signs of excessive stretching, any cracks in the case or even excessive corrosion, I would send that case to the Great Rifle Range in the Sky, first crushing it flat with a pair of pliers to make sure it won’t be used again.

If the brass is new—no matter the brand or reputation—I give it the same type of inspection. I’ve found cases of another caliber mixed in, cases with the flash hole drastically off-center or without a flash hole altogether, cases with rims bent beyond hope and so on.

If it’s fired brass, I use a universal decapping die to remove the spent primer and then begin the cleaning process. I use a combination of an ultrasonic cleaner to get out all the gunk and residue, along with a tumbler with some sort of media to polish the case after I’ve cleaned it.

Resizing Die

The resizing die is the next step; and if you want to get serious about things, you might want to measure the shoulder dimension of your fired cases against the SAAMI specification.

A must for precision reloading, a Redding Instant Indicator—with the SAAMI dummy for your chosen cartridge—will quickly and easily tell you where your chamber dimensions are in comparison to the specs and by adjusting the amount of shoulder bump through the use of Redding’s Competition Shellholders. You’ll then have a case with a shoulder-to-base dimension that matches your particular chamber; yet, it will have a diameter that complies with the SAAMI specification, allowing for easy feeding (unlike the hard bolt-close associated with neck-sized cases). This little trick has made some undeniable improvements in accuracy in more than a few rifles. If you find that your chamber has a variation of more than 0.002 inch from the SAAMI spec, I’d suggest looking into this technique for your precision rifle.

Bushing Die

Should you want to maximize your brass life, a bushing die can be used for resizing so that the case neck will be worked as little as possible. Measure the diameter of a few loaded cases, take an average of that dimension, and use the correlative bushing in the resizing die. Instead of shrinking the case neck and mouth to a dimension too much just to have the brass worked over the expander ball, the bushing dies only reduce the case diameter enough to give good neck tension. You’ll see longer case life and fewer cracked necks over time.

Load Up On Reloading Info:

- The Flexible And Forgiving .30-06 Springfield

- The .45 Colt: A Wheelgun Classic

- .300 Win. Mag.: The Answer To Most Hunting Questions

- Tips For Reloading the .223 Remington

Trimming To Length

Trimming cases to length is important because it aids in uniformity of neck tension and gives a good, square case mouth. The trimming process will leave burrs on both the inside and outside of the case mouth, so they’ll need to be removed for both ease of feeding (on the outside of the case mouth), as well as for smooth bullet seating (on the inside of the case mouth).

If you want to get geeky with a specialized precision reloading tool, a precision chamfer tool will put a uniform chamfer on the inside of your case mouth. Redding makes a cool one—the Model 15P, which uses the flash hole as a pilot hole, making the chamfer as square to the centerline of the case as the flash hole is centered in the primer pocket.

Out Of Your Control

Although it might seem at this point that you’ve taken nearly every step and precaution to have the most uniform cartridge cases possible, there are some problems you can’t solve.

If your primer pockets are too small, you can use a reamer to bring them to the proper dimension. However, if you’re shooting a high-pressure load, you might find that the primers seat much too easily. What has happened is that the primer pocket has stretched. I know no remedy for this situation, and the case should be destroyed.

Neck wall thickness is another dimension completely out of your control. Sorting your cases by neck uniformity is a great idea, because the most uniform case necks will give the best concentricity, which usually equals the best accuracy. Large variations in case neck thickness are irreparable, and those cases showing neck thickness variations of more than .0015 inch should be set aside and not used for precision reloading projects.

Grab a Redding Case Neck Gauge, and you’ll quickly and easily be able to see exactly what’s going on with your brass. Because this gauge uses a large indicator dial, an appropriately sized mandrel and a caliber-specific pilot stop, it’s a simple and effective tool. Place the resized and expanded case on the pilot stop, which will push the alignment pin through the flash hole, and the set probe of the dial to touch the center of the case neck. Set the dial to zero and rotate the case 90 degrees at a time, observing the measurements carefully and setting aside any out-of-spec cases.

Just as if you had bullets that weren’t the proper diameter, a case with a neck thickness of improper consistency will certainly not be centered in the case. Therefore, it won’t be aligned with the rifle’s bore. If you’re starting with components that are out of alignment, you can easily see how it would be nearly impossible to come out of the reloading process with precise ammunition.

Take the time and make the effort in preparing your cases, and you’ll be much happier when you walk downrange and examine your targets.

The article originally appeared in the October 2019 issue of Gun Digest the Magazine.

![Best Concealed Carry Guns In 2025 [Field Tested] Wilson Combat EDC X9S 1](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Wilson-Combat-EDC-X9S-1-324x160.jpg)

![Best 9mm Carbine: Affordable PCCs [Tested] Ruger Carbine Shooting](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Ruger-Carbine-Shooting-100x70.jpg)

![Best AR-15: Top Options Available Today [Field Tested] Harrington and Richardson PSA XM177E2 feature](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Harrington-and-Richardson-PSA-XM177E2-feature-100x70.jpg)