The Tikka T3 and T3x aren't only budget-friendly, top-performers. The Finnish rifles are also easily customized to excel in any endeavor.

In 1918, Finnish firearms company Tikkakoski started to manufacture firearms components. Sixty-three years later, Tikkakoski and another Finnish firearms company, Sako, collaborated on a prototype rifle. Sako then purchased Tikkakoski from Nokia in 1983. The companies merged to create Oy Sako-Tikka Ab, which later became Sako. A world-class manufacturer of hunting, law enforcement and military rifles, Sako positioned the Tikka brand as a “budget” class of rifles. The Beretta Holdings Group purchased Sako in 2000, and in 2003 the Tikka T3 rifle was released to the market. After over a decade of success with the Tikka T3, Tikka released an updated version, the Tikka T3x, which debuted in 2016.

Being Sako’s budget brand does not mean these rifles are cheap or of poor quality. The Tikka T3 has been well-received by the U.S. market and is noted for its accuracy, versatility and excellent trigger. Tikka offers models for hunting, law enforcement, and precision-rifle applications.

Tikka offers the T3 and T3x exclusively as long-action rifles. The actions have a round bottom and calibers run from .204 Ruger up to .300 Winchester Magnum. Many gunsmiths will note that the Tikka action tends to be true and requires little blueprinting. Like the universal action size, Tikka uses one magazine size with internal magazine blocks to accommodate the different calibers. Bolt travel differs based on cartridge length, with Tikka using two different bolt stops, depending on the caliber.

The action is secured by two M6 metric thread action screws, and mates with the stock via an aluminum recoil lug. Tikka offers rifles that have an integrated Picatinny scope base, and some with a plain dovetail that can accept proprietary scope rings. The single-stage trigger on the Tikka T3/T3x is user adjustable between 2 and 4 pounds. The trigger is crisp and noted as one of the best factory triggers available. Both Tikka and Sako barrels are cold hammer-forged and are made side by side in the same factory. Tikka guarantees a five-shot 1-MOA guarantee on its heavy barrel rifles, and a three-shot 1-MOA guarantee on its sporter barrel rifles.

The Tikka rifle receiver features broached raceways to accommodate the two lugs on the bolt. Bolt throw is 70 degrees, and the Tikka T3/T3x has one of the smoothest actions on the market. The bolt has a Sako-style extractor and a spring-and-plunger ejector. The bolt handle is dovetailed into the bolt and can easily be removed by the end-user. The shroud on the Tikka T3 bolt is polymer and, like the bolt handle, it can easily be customized with an aftermarket option. The Tikka T3x bolt shrouds are aluminum. The bottom metal is constructed of polymer on both the Tikka T3 and T3x.

Tikka launched the Tikka T3x in 2016 and made changes to both the receiver and the stock. On the receiver, Tikka opened up the ejection port, which allows users to easily feed one round at a time. Tikka replaced the polymer bolt shroud with an aluminum one and changed the aluminum stock lug to steel. The steel lug addressed deformation issues that had occurred with large-caliber rifles. The top of the receiver was drilled and tapped to accommodate a Picatinny rail; this modification was also possible with the Tikka T3, but Tikka felt there was room for improvement.

The most significant aesthetic change was the inclusion of a modular stock that features interchangeable pistol grips and fore-ends. Through the Beretta store, customers can purchase grips and fore-ends with different textures, sizes and colors. The stock is filled with foam inserts to dampen noise, and an enhanced recoil pad mitigates felt recoil.

Tikka T3/T3x Analysis

Over the years, I have owned a suite of Tikka T3 and Tikka T3x rifles. To me, the Tikka T3/T3x is analogous to a Glock 19: It is an inexpensive, quality firearm that simply performs. I am not afraid to damage it and will modify it to suit my needs. I rarely get attached to my stock Tikkas and see them as tools to perform a given task. These tough rifles can be easily customized and tend to hold their value. I have never owned one that failed to hold MOA, given good factory ammunition and solid shooting fundamentals.

Tikka’s feed from a polymer magazine. Tikka uses blocks in the magazine to accommodate the various caliber configurations. Metal magazines do exist, though the author never had a problem with the factory polymer magazines.

For years, I thought the Tikka T3 was good out of the box, but after owning a few Tikka T3x rifles, I appreciate the upgrade. A common complaint about the Tikka T3 bolt was the plastic bolt shroud. I never took issue with this or had one fail in the field, but I am glad Tikka addressed this issue by making an aluminum bolt shroud standard on the Tikka T3x series. The custom grip and fore-ends are a nice touch, and the larger ejection port does ease loading of single rounds. Did I ever have problems after attaching a Picatinny rail to my Tikka T3? No, but if user feedback demanded a more solid rail interface, I am glad Tikka took note and put its engineers to work upgrading this component on the Tikka T3x. Tikka offers both right- and left-handed models.

Modifying The Tikka T3/T3x

Except for the Tikka T3x CTR, T3x UPR, T3x TACT A1, and the Tikka T3 Super Varmint, Tikkas do not have a Picatinny scope base. The rifles without scope bases use a specialized scope ring, which is readily available from a variety of manufacturers. These rings mount directly to the top of the receiver. In my experience, this is a lightweight, streamlined way to install a scope. If you attach a Picatinny scope base, this modification will raise up your scope and you might need to raise your comb height to ensure a proper cheek weld. This subsequent adjustment is paramount if you train and shoot in the prone position. Raising the comb can be accomplished either by building up the comb with tape and padding or by installing a nylon comb riser/ammo pouch. Kalix Teknik of Sweden makes a retrofit kit that looks like it was installed at the factory and requires only a slight modification to the rifle. The CR-1 has an adjustable comb, secured inside the rifle buttstock by an aluminum assembly. A knob on the stock allows the user to secure the comb at the desired height. In my opinion, the Kalix Teknik CR-1 is the best aftermarket accessory currently available for adjusting comb height.

Except for the T3x TACT A1, Tikka rifles tend to be on the lighter side in terms of weight. A lightweight rifle is fantastic to carry around the woods all day. The only drawback of a lightweight rifle is increased recoil. The easiest way to decrease recoil on a lightweight hunting rifle is to add a muzzle brake and a recoil pad. If you do add a muzzle brake, hunting with hearing protection is absolutely mandatory. Training and getting proficient with a light rifle are easier when excessive recoil is mitigated. This adjustment is particularly important for small-statured or new shooters.

If I wanted to set up the optimal Tikka T3/T3x for a lightweight hunting rifle, I would start with a Tikka T3/T3x Lite and install a LimbSaver buttpad. Tikka did upgrade the buttpad on the T3x rifles, but I think a LimbSaver is still superior to the factory product. If, after installing a Limbsaver recoil pad, I cannot comfortably zero a rifle and gather ballistic data out to 600 yards on an 8-inch steel plate, I will consider a muzzle brake. My 6.5 Creedmoor backcountry hunting rifle did not require a brake and was a joy to shoot, even in the prone position. My .308 Winchester and .300 Winchester Short Magnum both have muzzle brakes.

I also would replace the polymer bottom metal with an aluminum bottom metal from High Desert Rifle Works. An aluminum bottom metal mitigates fliers and increases the tension between the action and the stock. Though anecdotal, I believe that an aluminum bottom metal leads to a more accurate rifle by positively affecting barrel harmonics, and it will never crack. Unfortunately, I have had factory Tikka polymer bottom metals break, where the action screws interface with the bottom metal. In my home state of New Mexico, it can be near freezing in the morning and 95 degrees in the afternoon. This heating-and-cooling cycle is tough on polymers, and all my backcountry Tikkas have aluminum bottom metals.

One area where I don’t mind weight is in my rifle scope. Hunting in the West requires quality glass and, potentially, 400- to 500-yard, cross-canyon shots. For a scope, I would select a TRACT TORIC UHD 30mm. These top-of-the-line scopes use premium glass and feature a MIL-based reticle that allows you to hold for elevation and wind.

For a general-use rifle where weight is not a concern, I would install a muzzle brake and look at a stock with more features, like adjustable length of pull and comb height, and modular interfaces for bipod and sling attachment. Suitable candidates would include the Boyds At-One Thumbhole Stock, Kinetic Research Group Bravo stock, and my new favorite, the Modular Driven Technologies XRS. I would also consider attaching a suppressor to the rifle.

Custom Tikkas

Since the Tikka T3/T3x is a long action, it has a lot of versatility for caliber selection and is perfect for a custom rifle. About 10 years ago, I found a .300 WSM in a gun store being sold for $275. I asked the clerk why the rifle was so cheap, and he responded that the seller found the recoil to be hellacious and could not effectively use the rifle. Twenty minutes later, I was the new owner of a Tikka T3 chambered in .300 WSM. I threw the rifle in my safe and forgot about it. Fast forward to the 2018 SHOT Show, where I first saw the 6.5 PRC round from Hornady. When I got home from SHOT Show, I contacted Bill Marr at 782 Custom Gunworks and inquired about rebuilding my .300 WSM into a 6.5 PRC. Bill said it wasn’t a problem, and noted that my request couldn’t have come at a better time because he had just received a 6.5 PRC reamer. I shipped my Tikka T3 to Long Island, New York, and, several weeks later, received a custom Tikka rifle. The rifle featured a 26-inch 1:8-inch twist Shilen Select Match Barrel, and the barreled action was mated to a Kinetic Research Group Bravo chassis. The rifle launches 147-grain Hornady ELD-M rounds at 2,920 fps, and can easily hold five-shot, sub-.40-inch groups.

The rifle was immediately put to work dispatching coyotes at long range and has been used on several long-range antelope hunts. I can get consistent hits on a 24-inch plate at 2,000 yards and, besides long-range predator control, I use the rifle when I have to test optics and optical accessories past 1,800 yards. The only change I have made was swapping out the Kinetic Research Group Bravo chassis for a Modular Driven Technologies ESS Chassis. The Modular Driven Technologies chassis has better comb and buttpad adjustments and complements lights, lasers, and clip-on thermal and night-vision technology.

If you have an old Tikka T3/T3x that you want to rebuild or customize, contact 782 Custom Gunwerks, or Oregon Mountain Rifle Company. 782 Custom Gunwerks is one of the premier gunsmiths in the United States and has expertise in building custom Tikkas. Bill Marr, the owner and lead gunsmith, can do anything you want to a Tikka. Oregon Mountain Rifle Company offers a Tikka T3/T3x Upgrade Package, in which it installs a carbon-fiber barrel, muzzle brake and carbon-fiber stock.

Closing Thoughts

The Tikka T3/T3x are fantastic rifles. Tikka rifles start at around $550 for a Tikka T3x Lite model and go all the way to $1,800 for a chassis-style Tikka T3x TAC A1. These rifles can be purchased stock and immediately put to work, or customized to meet a particular use. In the last several years, I have observed a robust aftermarket segment materialize.

At the 2018 SHOT Show, Tikka released the Tikka T1x MTR, a rimfire chambered in .22 LR and .17 HMR. These rifles are perfect for training and hunting, and are extremely popular in the NRL22, a .22-caliber-specific league of the National Rifle League. At the 2020 SHOT Show, Tikka released four new models. The T3x Lite Veil Wideland and Veil Alpine feature fluted barrels and bolts for weight reduction, muzzle brakes and a nice hydrographic camo pattern on the stock. The T3x Lite Roughtech is similar to the Veil in that it has a fluted barrel and bolt and a muzzle brake, but has a textured stock that provides extra grip in inclement weather conditions. The final rifle debuted was the Tikka T3x UPR, or Ultimate Precision Rifle. The UPR has a modern, but traditional, form factor, adjustable comb, threaded, medium-profile barrel, and a 0- or 20-MOA scope base. This rifle is optimal for precision-rifle applications. The Tikka lineage has been producing firearms and firearms components for over 100 years. Tikka’s are my go-to rifles, and I am excited to see what this company does in the coming years.

For more information on Tikka rifles, please visit tikka.fi/en-us.

Editor's Note: This article is an excerpt from Gun Digest 2021, 75th Edition available now at GunDigestStore.com.

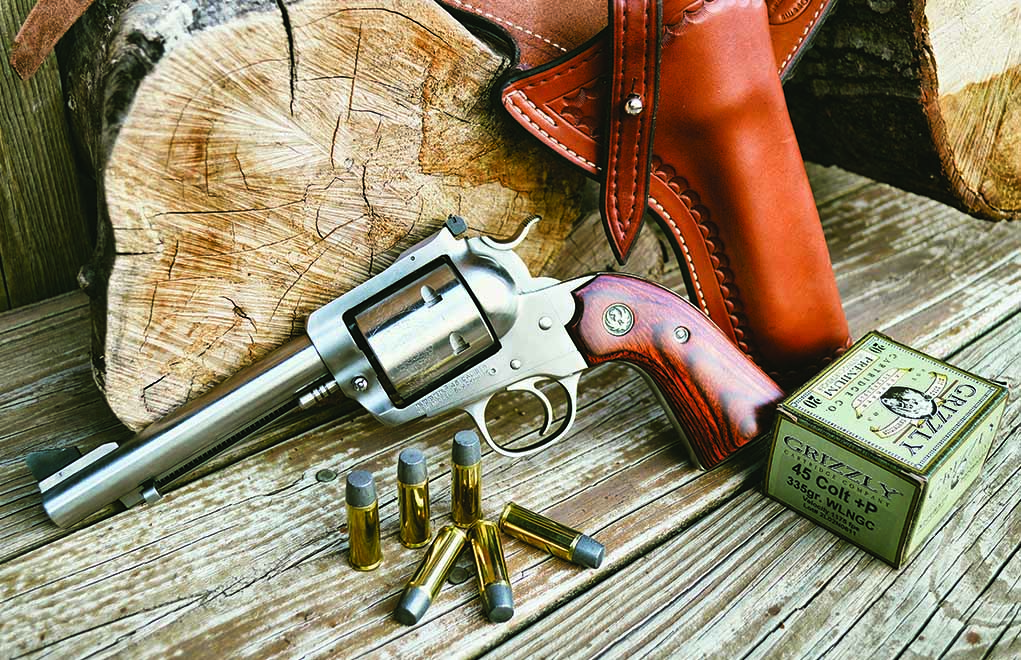

Gun Digest Book of Hunting Revolvers. It was an ambitious plan, with many moving parts that ultimately fell just short of completion. Nevertheless, a truncated version ended up in the book—despite my best efforts!

Gun Digest Book of Hunting Revolvers. It was an ambitious plan, with many moving parts that ultimately fell just short of completion. Nevertheless, a truncated version ended up in the book—despite my best efforts!

![Best Concealed Carry Guns In 2025 [Field Tested] Wilson Combat EDC X9S 1](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Wilson-Combat-EDC-X9S-1-324x160.jpg)

![Best 9mm Carbine: Affordable PCCs [Tested] Ruger Carbine Shooting](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Ruger-Carbine-Shooting-100x70.jpg)

![Best AR-15: Top Options Available Today [Field Tested] Harrington and Richardson PSA XM177E2 feature](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Harrington-and-Richardson-PSA-XM177E2-feature-100x70.jpg)