We discuss different kinds of body armor, NIJ rating levels and the best Level 4 plates on the market.

Whether you’re a tactical gear enthusiast or an armed guard or police officer who must supply their equipment, you've probably heard that Level 4 plates are what you should get.

We're going to tell you why, what different levels and features mean and then look at the best types of Level 4 plates (or Level 4 body armor) to buy.

We’re also going to explain why you need to pay close attention to what the various companies selling body armor say about their products. A lot of people have been sold a tactical pig in a poke, so you might as well get the real deal.

What Is Hard Armor?

Hard armor employs plates made of rigid materials, such as ceramic or (less desirable) steel. These plates are usually worn in a plate carrier over clothing, protecting the vital organs on the front, back, and sometimes the sides. In contrast, soft armor is made from woven materials like Kevlar slow and stop bullets from penetrating.

Generally speaking, hard armor is effective against high velocity threats, such as rifles, while soft armor can only stop low-velocity projectiles, such as handgun fire. This makes sense, given hard armor was developed for and initially used by the military. Though, through the years plate armor has tricked its way into law enforcement and civilian use, each seeking greater protection.

Body Armor Legalities

Federally, body armor is legal to own and use for anyone over the age of 18 who has not been convicted of a felony. Be aware, however, that some states have passed or attempted to pass laws restricting body armor. If you're in the market, it pays to keep up to date with your local laws.

For instance, in Connecticut, body armor can only be sold or bought in person, and New York has outlawed the purchase of body armor except for certain approved professions. Further, most states also have laws prohibiting the use of body armor while committing a crime.

Hard Armor Material

There are three general types of materials that hard armor is made from:

- Metal

- Ceramic

- Polyethylene

Metal Body Armor

Metal body armor plates are usually made from steel, but titanium armor exists. Steel plates are generally the cheapest of all types of hard armor but are so for a reason. Armor made of AR500 steel, for instance, can be defeated by certain loads of high velocity 5.56. When struck by a bullet, it also creates spall, tiny fragments of metal that fly away from the impact.

To minimize this, steel plates are usually coated in a truck bed liner-like material designed to catch spall. It doesn’t always do so which can prove dangerous.

Steel is, of course, also very heavy. You won’t have fun if you have to wear it for any length of time, especially if you’re moving.

Ceramic Body Armor

Ceramic armor plates are typically made of boron carbide. Quality ceramic plates offer better protection against high-velocity projectiles and don't have the same problem with spalling.

They're lighter than steel but also more expensive, although they have been getting consistently more affordable as body armor has become more popular. SAPI/ESAPI plates, the ones issued by the U.S. military, are ceramic. That is a big, big clue about what kind of plates you should buy if you want the best protection.

Polyethylene Body Armor

Poly armor plates are made of polyethylene, specifically Ultra High Molecular Weight Polyethylene (UHMWPE). They are lighter than steel, but generally also bulkier and tend to fare worse than ceramic armor against high-velocity rifle bullets and anything with an armor-piercing projectile.

Some companies also make hybrid armor using a composite of these three materials.

Keep in mind that some hard armors are intended for use in conjunction with soft armor or a plate backer to get the best protection possible. Make sure you look closely at the fine print of whatever plate you're looking at.

NIJ Certification And How “Level 4 Armor” Might Not Be Level 4

The NIJ, or National Institute of Justice, tests body armor and certifies it for absorbing a particular threshold of abuse by bullets. NIJ testing and certification in and of itself is a very complex topic with plenty of nuances, but we'll try to give you the basics.

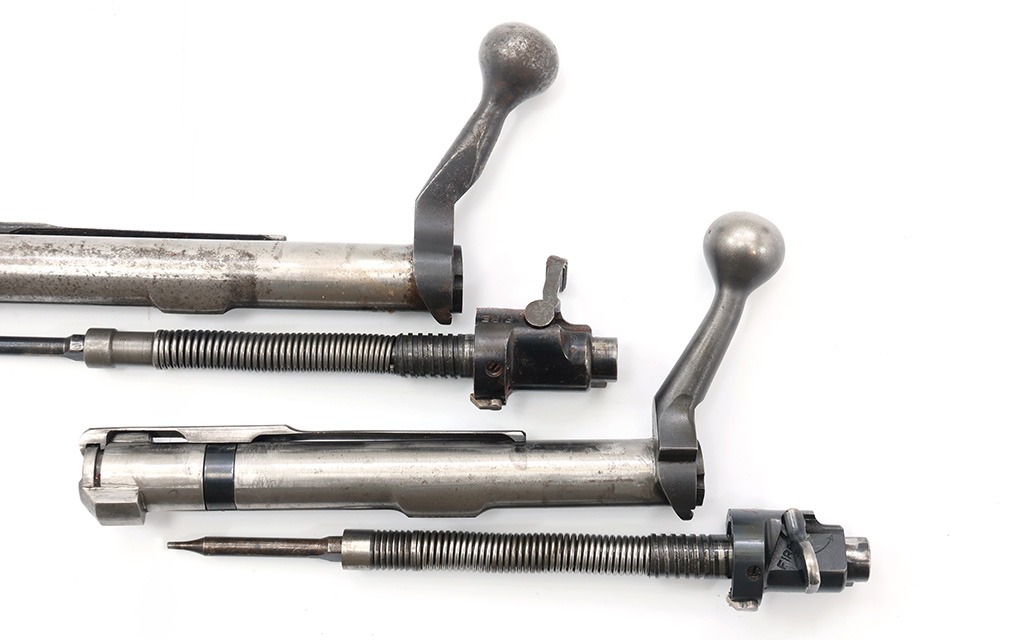

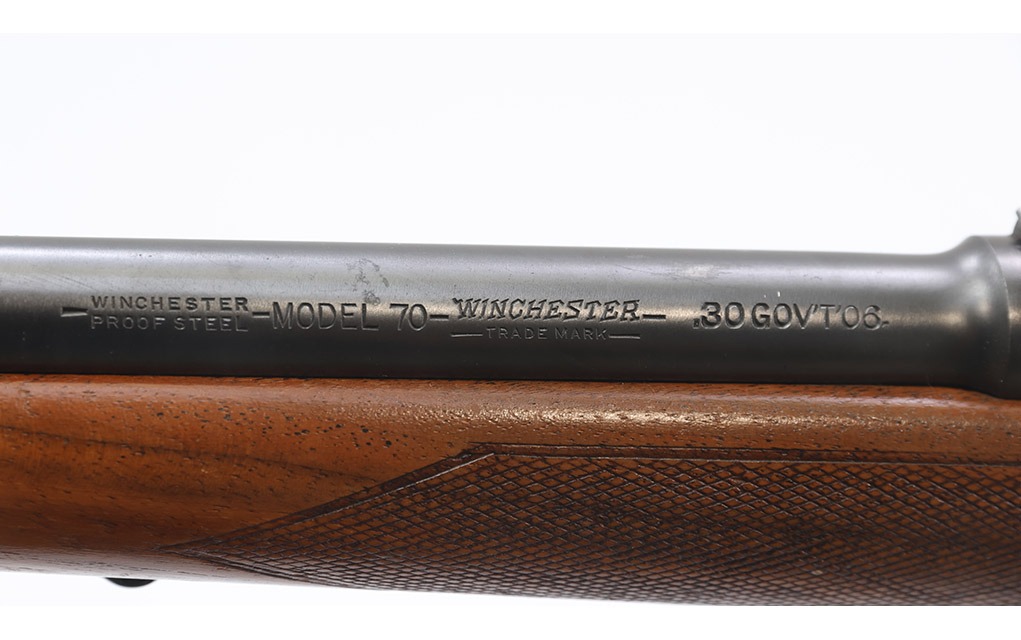

The NIJ standards determine whether a particular piece of armor will defeat a specific threat. For instance, to be rated Level 4, armor plate must stop a .30-06 armor-piercing (M2 black tip) round. You can read more about the levels here, but the short answer is Level 4 is the highest tier and will offer the greatest protection. The NIJ has the testing done by certified third-party laboratories, with tests repeated six times over five years.

The levels are officially called IIA, II, III, IIIA, and IV, but they’re commonly written using standard rather than Roman numerals when discussing them. There is no NIJ+ rating. That’s just a marketing term like Corinthian leather.

After five years, any make and model of plate must be recertified.

Here's something else you need to know.

Not every armor manufacturer actually submits products to the NIJ, they just replicate the test…or perform their version of it. So, just because somebody says their body armor is Level 4, it doesn't mean it is.

To save yourself the trouble of worrying, here's the NIJ's list of compliant body armor manufacturers and their products that are (or have been) rated by the NIJ.

The best practice is that if body armor is not certified by the NIJ, don't buy it. Do not take the manufacturer's word for it. Look it up for yourself and verify.

That said, just because a certification is inactive doesn't mean it isn't quality armor. The manufacturer has just elected not to re-certify, usually because the product is being updated into a new version.

Body Armor Plate Cuts & Other Considerations

If you’ve picked up what the last section was laying down, you should understand that to get the best protection possible you’re going to need NIJ-certified ceramic Level 4 plates. There are other factors to consider like the plates’ size and shape.

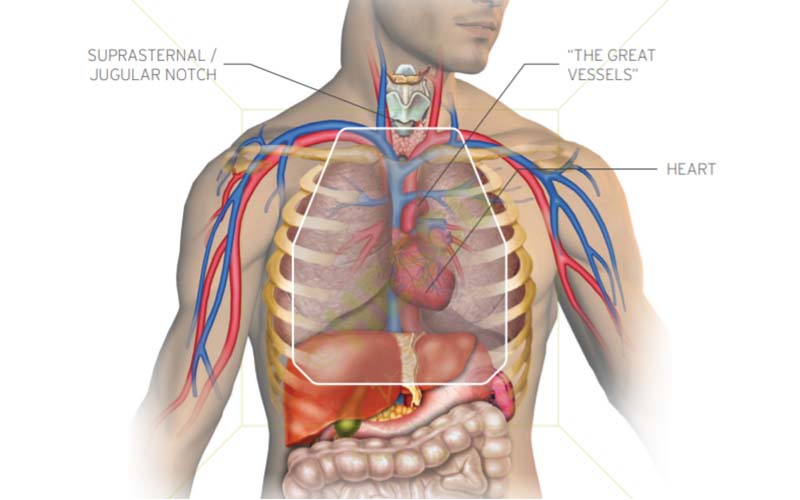

Body armor plates come in different sizes, and you’ll need to pick a size that is large enough to cover your vital organs without being so big that it inhibits your movement. A widely accepted guideline for that is your plate should span horizontally from nipple to nipple and vertically from your suprasternal notch to just above your belly button.

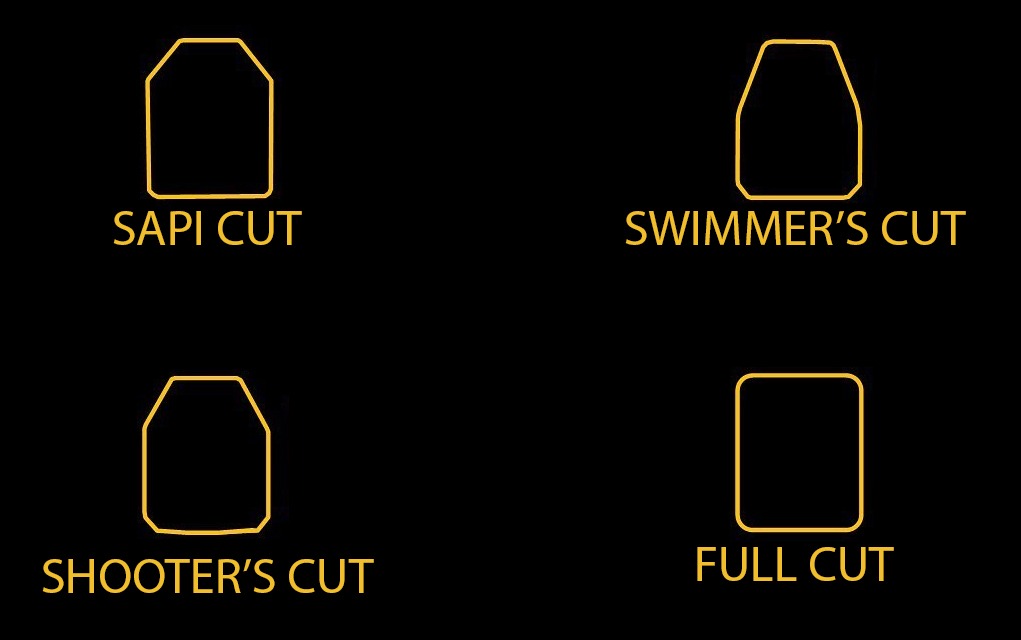

Body armor plates have different cuts, and each style offers a balance between coverage and shoulder mobility. The four most popular shapes are the Full Cut, Swimmer’s Cut, Shooter's Cut, and the SAPI (Small Arms Protective Insert, the one specified by the U.S. military) Cut. The exact dimensions of each cut may vary between manufacturers.

Full Cut: A rectangle or square with rounded or chopped corners. This gives you the most coverage but is most likely to impede upper body movement, though it can be dealt with.

Shooter's Cut: A chamfered Full Cut plate, cutting the top few inches of the corners at a 45-degree angle to free up a little more room for arm movement or shouldering a rifle.

Swimmer’s Cut: Similar to the Shooter’s Cut but it increases that taper, freeing up even more room to move the arms while sacrificing a little more coverage. It may be enough of a reduction that the tops of your vitals could be exposed.

SAPI Cut: Specified by the military, is very similar to the Shooter's Cut but has less generously cut corners and provides a little more coverage.

Most people find a SAPI or Shooter's Cut strikes the right balance, but some prefer the easier movement of a Swimmer's cut. It's also not uncommon at all for somebody to use a SAPI or Shooter’s Cut plate in the front and a Full Cut plate in the back.

Additionally, Level 4 plates from different manufacturers can have different thicknesses and weights, something else to pay attention to when considering what will best fit your needs. When all things are equal protection-wise, thinner and lighter is always better, but those plates are going to cost more.

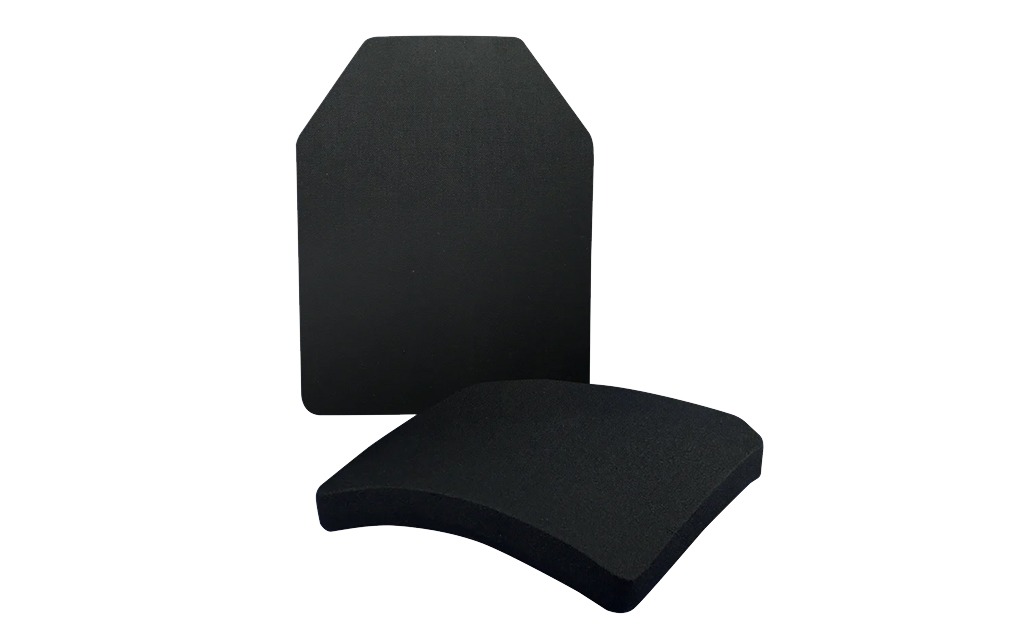

The final hard armor plate feature to remain aware of is single-curve versus multi-curve plates. In a nutshell, multi-curve plates are more comfortable, but are also harder to manufacture and therefore more expensive. If you want maximum comfort, it’s probably worth shelling out the extra money. But single-curve plates work perfectly fine for most people too.

How We Made Our Picks

There’s a lot of good body armor out there, including models not listed here, but it wasn’t too hard for us to narrow our favorite picks down to these five options. All of these are currently NIJ-certified ceramic Level 4 plates from a variety of trusted, reputable manufacturers. They vary mostly in features such as their cut and size options and details like weight and thickness. Once you pick the plates you want, just ensure that whatever plate carrier you buy is sized correctly to accommodate them.

The 5 Best Level 4 Plates:

Most of these Level 4 plates are available in different sizes and cuts, so we’ll be using specs for the medium-size SAPI Cut option whenever possible for the sake of consistency. Further, some of these plates appear to only be sold in sets of two, so we will be calculating the cost of a single plate when listing each price.

| ARMOR | Size/Cut | NIJ Certified? | Thickness | Weight | Price |

| Hesco 4601 | 9.5×12.5″ SAPI Cut | Yes | 1.18″ | 6.6 lbs. | ~$553 |

| Velocity Systems PSA Stand-Alone Level IV | 10×12″ Shooter's Cut | Yes | 0.75″ | 6.8 lbs. | ~$305 |

| LTC 26605 Level IV Multi-Curve Plate Set | 9.5×12.5″ SAPI Cut | Yes | 1″ | 7.5 lbs. | ~$360 |

| TenCate Cratus 5200 Level IV Multi Curve Plate | 10×12: SAPI Cut | Yes | 1.3″ | 7.2 lbs. | ~$700 |

| Highcom Guardian 4s17m | 9.5×12.5″ SAPI Cut | Yes | 0.95″ | 8.2 lbs. | ~$240 |

Hesco 4601

Specs (9.5×12.5″ SAPI Cut)

NIJ Certified Level 4: Yes, active

Thickness: 1.18 Inches

Weight: 6.6 Pounds

Price Per Plate: ~$553

Website: hesco.com

Pros

- Decent number of sizes and cut options

- Good balance between weight and price for the quality

Cons

- Expensive

- Fairly thick

Hesco is as close to a no-brainer as it gets. They are a U.S. government supplier, and the 4601 is currently NIJ-certified Level 4.

It's plates are available in a SAPI Cut with four size options or a Shooter’s Cut with two size options. The armor may be pricey, but it should offer excellent protection while being comfortable to wear thanks to the multi-curve contour. They are sold as either sets or as standalone plates depending on the retailer.

Velocity Systems PSA Stand-Alone Level IV

Specs (10×12″ Shooter's Cut)

NIJ Certified Level 4: Yes, active

Thickness: 0.75 Inches

Weight: 6.8 Pounds

Price Per Plate: ~$305

Website: velsyst.com

Pros

- Thin and light

- Relatively affordable

Cons

- Only available in 10×12″ Shooter's Cut

Velocity Systems produces quality tactical gear for LE and military personnel, including its line of hard armor plates. The PSA Stand-Alone Level 4 plate is a ceramic Level 4 plate with current NIJ certification.

The plate is only available in a 10×12-inch size with a Shooter's Cut that's a little steeper than most other options for better mobility. Velocity Systems doesn’t sell to civilians directly and instead sells them through retailers such as Brownells.

LTC 26605 Level IV Multi-Curve Plate Set

Specs (9.5×12.5″ SAPI Cut)

NIJ Certified Level 4: Yes, active

Thickness: 1 Inch

Weight: 7.5 Pounds

Price Per Plate: ~$360

Website: ltc-ltc.com

Pros

- Balance of protection, thickness and price

- Decent amount of size and cut options

Cons

- Heavy

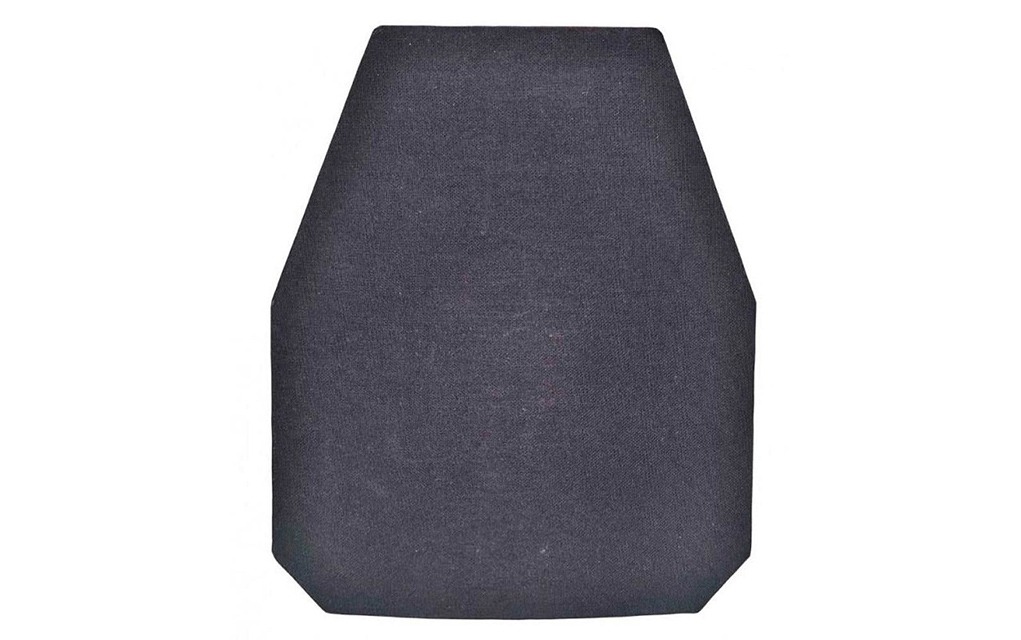

Leading Technology Composites is one of the largest ceramic armor plate manufacturers in the world, and their 26605 plates are currently NIJ certified Level 4. Level 4 plates in a Swimmer's Cut from a reputable manufacturer are not the easiest thing to find, so those looking for one will find few better options. They’re available with a SAPI Cut as well and come in several sizes.

The 26605 plates feature a triple-curve with a ceramic core, aramid fiber backing, Cordura cover and a foam-covered strike face.

TenCate Cratus 5200 Level IV Multi Curve Plate

Specs (10×12: SAPI Cut)

NIJ Certified Level 4: Yes, active

Thickness: 1.3 Inches

Weight: 7.2 Pounds

Price Per Plate: ~$700

Website: integriscomposites.com

Pros

- Size options, including side plates available

Cons

- Heavy and thick

- Expensive

The TenCate Cratus series is frequently white-labeled by other brands due to its incredible performance, and the 5200 series (model D1581) is currently NIJ-certified for Level 4 protection.

The Tencate Cratus 5200 Level IV Multi Curve Plate is a multi-curve SAPI Cut plate with a polyurethane cover. They’re available in seven different front/back plate sizes and have side plate options as well.

Highcom Guardian 4s17m

Specs (9.5×12.5″ SAPI Cut)

NIJ Certified Level 4: Yes, active

Thickness: 0.95 Inches

Weight: 8.2 Pounds

Price Per Plate: ~$240

Website: highcomarmor.com

Pros

- Great performance and thickness for the price

- Affordable

Cons

- Heavy

- Only two size options

The Highcom Guardian 4s17m plate is a solid working man’s option in sets of two plates that are often under $500 and are frequently bundled with a plate carrier for less than $700.

Highcom plates are currently NIJ certified and are offered in five sizes of SAPI Cuts as well as one 10×12-inch Shooter’s Cut option, but all are multi-curve. If you're looking for a turn-key option they're hard to beat.

More On Body Armor & Related Gear:

- Premier Body Armor Everyday Armor T-Shirt

- Pick The Best Plate Carrier: Complete Buyer's Guide

- Plate Carrier Setup: Weighing The Options

- Plate Carrier Accessories: What, Where And Why?

- Choosing A Plate Carrier Backpack

![Best Concealed Carry Guns In 2025 [Field Tested] Wilson Combat EDC X9S 1](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Wilson-Combat-EDC-X9S-1-324x160.jpg)

![Best 9mm Carbine: Affordable PCCs [Tested] Ruger Carbine Shooting](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Ruger-Carbine-Shooting-100x70.jpg)

![Best AR-15: Top Options Available Today [Field Tested] Harrington and Richardson PSA XM177E2 feature](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Harrington-and-Richardson-PSA-XM177E2-feature-100x70.jpg)