We pieced together a custom Thompson Center Contender carbine, so let’s take a look at the build process, the parts used and assess the final product.

Even a very brief look at a rifle beyond my financial means fueled my desire to build one close to it. The rifle in question was a custom one-off falling-block rifle made in Europe. It was chambered in .22 Hornet and had magnificent case colors adorning the frame. Marketed as a gentleman’s rifle for fox hunting, it was going to be sold at the Safari Club International annual hunter’s show in Reno, Nevada, for a few bills higher than a Rolex Presidential model.

The seeds were sown, and visions of a case-hardened Thompson Center Contender came to mind with a fancy stock and a Leupold scope. With a spare old-model first-generation frame gathering dust in the safe and a Leupold scope sitting around, the only things needed to finish this project were a barrel, rings and an attractive stock. And someone willing to apply the color case-hardening. Challenge accepted!

Thompson Center History

When it was first rolled out in 1967, the Thompson Center Contender was mostly a novelty. The barrels were all below 10 inches in length, octagonal in shape and mostly represented the lower end of the power spectrum (.22 Jet, .22 LR, .38 Special, etc.). They were accurate, but not particularly useful beyond the firing line at the local outdoor range.

By the 1970s, the barrels took on a round shape and were offered in rifle calibers such as .223 Remington, .30-30 Winchester, .35 Remington and .45-70. Magnum handgun calibers, such as .357 Magnum, .41 Magnum, .44 Magnum, .357 Maximum and .45 Winchester Magnum followed, and the Contender was reborn as a highly accurate long-distance pistol for metallic silhouette shooting and as a suitable hunting arm in either rifle or pistol configuration. Thompson Center even made a variant in .45 Colt/410 shotgun with a rifled barrel and removable choke tube, some complete with a ventilated rib and brass bead front sight.

Part of the beauty of a Contender is that you can change calibers in a matter of minutes. Remove the forend with a screwdriver, pop out the hinge pin, remove the barrel, install the new one, replace the hinge pin and the forend … and you’re done. There’s no need to fit, check headspace or set cylinder gap. Additionally, there’s no need to re-sight the Contender, as the sights or optics are mounted on the barrel. Your zero is always maintained.

Because there’s a 52-year manufacturing period with small changes here and there, some older barrel-and-frame combinations might require fitting. This has mostly been eliminated with the newest incarnation of the Contender, known as the G2 frame, that debuted in 1998. However, even the most accurate barrels and custom frames can still be a bit tight fitting. The biggest complaint, outside of being a single-shot firearm, is having to slap the barrel down to get it to break open at times with the older models. The older models, however, do have a better trigger than the G2.

Although mostly known as single-shot pistols, rifle-length barrels and a buttstock can be attached to the Contender to give the shooter a single-shot rifle.

As a matter of fact, the Thompson Center Arms company offered a kit, including a 21-inch rifle barrel, a 10-inch pistol barrel, a pistol grip and a buttstock back in the 1980s. The ATF brought the charge that such a kit was a potential National Firearms Act weapon because a shooter could attach a buttstock to a Contender with a short barrel.

The Supreme Court held that a short-barreled rifle “actually must be assembled” in order to be “made” within the NFA’s definition. This is one of the few firearms where you can legally go from rifle to pistol and back again.

Smith & Wesson purchased Thompson Center Arms in 2007, pretty much for the company’s barrel-making capabilities. In the 15 years since then, very few Contenders and Encores have been released, and their caliber selection and barrel lengths dwindled from more than 100 combinations to less than a dozen.

Piecing Together The Custom Thompson Center Contender:

The Frame

As stated previously, several generations of frames can be identified by the side plates, hammer and, of course, the serial number. The frame in question came in from an estate sale. The hammer is semi-skeletonized on the spur, with a lever allowing the shooter to switch between centerfire and rimfire. The side plate bears the machined engraving of a crouching mountain lion. This was Thompson Center Arms’ logo for decades.

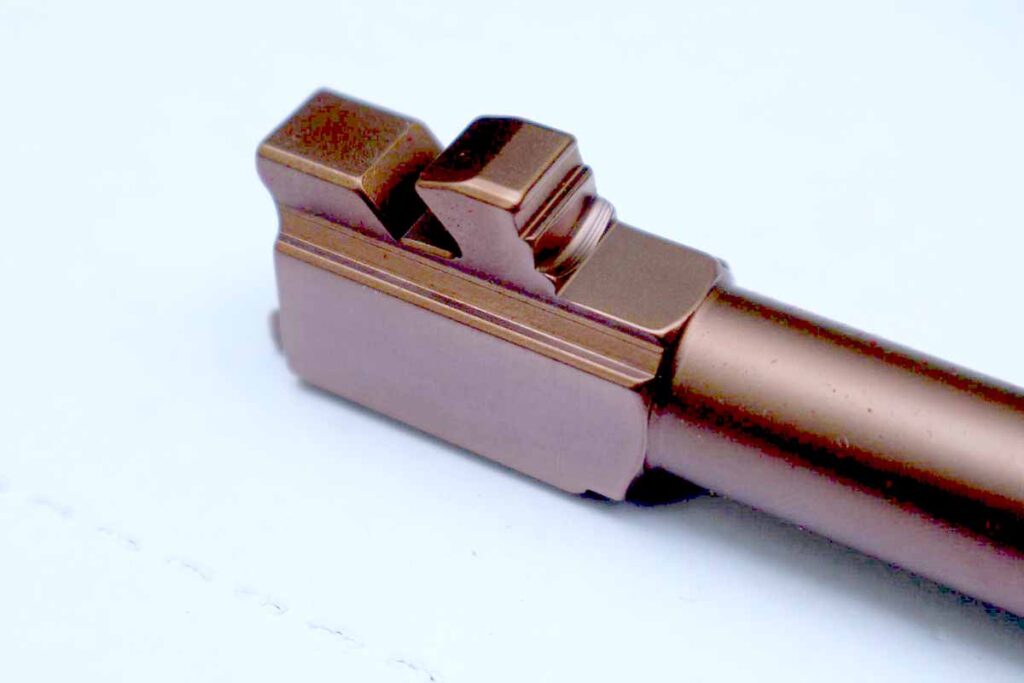

Finding a suitable barrel was a bit of a challenge. The G2 barrels aren’t backward compatible with the old frames, and the older barrels seem to be commanding a premium due to their scarcity. An online auction site revealed a 21-inch barrel chambered in 223 Remington and seemed perfect for this purpose. Best of all, the price was a mere $150.

Unfortunately, the barrel tended to stick after firing. It often took the use of a heavy rubber mallet to disengage it. This was something that would have to be looked into when it went out for color-case hardening.

Furniture

There’s nothing wrong with factory forends, stocks and grips from T/C Arms. While the synthetics always feel a bit flimsy, the walnut is actually very well done. The only problem seems to be availability and, of course, now “vintage” parts costing a premium.

There are other alternatives, though.

Boyds Gun Stocks produces amazingly beautiful stocks in walnut and a variety of laminates. I went with one of the Sterling Thumbhole Stocks in a Nutmeg pattern, which resembles a handsome hardwood—even though it’s laminated. Fitting furniture can be a bit tricky, as we’re considering at least three different frame generations and an almost infinite configuration of barrels. An extended stock bolt and forend screw were sourced from Ace Hardware and, before it was refinished, a working rifle was ready for initial testing.

The buttstock and forend came with sling swivel studs installed at the factory. A Harris bipod can be mounted to the forend if you want to shoot from the bench.

Optics

Knowing that the frame would be case-hardened, rings in a similar color were needed. The choice was Talley for a set of 1-inch rings and a base. The base was black, but the rings recalled the case colors of a prewar Colt Single Action Army. Instead of traditional vertical caps, these screws mount through the side.

The scope in question was a low-powered variable optic in the form of a Leupold Vari-X III, in 1.75×6 power with a tall target turret, allowing for adjustments at 1/8 MOA with each click. Its 1-inch tube fit the rings perfectly, and the 32mm objective allows for plenty of light transmission.

.223 Remington

This has always been one of the most popular choices for the Thompson Center Contender pistol. It’s an outstanding varmint round and a bit more affordable and versatile than the .22 Hornet on the original rifle that inspired this build.

Accuracy out of this rifle is nothing short of phenomenal. You can truly build a sub-MOA rifle (or pistol) with a Contender in most cases. This has to do with the 1.5-pound trigger, limited moving parts during the firing sequence, and a completely sealed action (which can make for the quietest suppressor host), and you get the full power of the cartridge every time. There’s no loss of gas or power bleed-off whatsoever.

Gunsmithing The Contender

Color-case hardening is an art, and it’s associated with some pretty hazardous chemicals to get it correct. Case hardening stems from the mid-19th century, when metals weren’t the greatest, and a heat treatment was needed to make the firearm or tool stronger. It has an attractive color to some shooters and is mostly for decorative purposes now.

Bobby Tyler is a master gunsmith who works his magic with case coloring on everything from derringers and revolvers, to Sharps rifles and Contenders. He vowed to also fit the barrel to the action better as well as anything else that came up.

It turned out that the hammer cracked on this frame at some point between the last shooting session and when the gun was being taken apart for refinishing. Sourcing an original hammer took quite some time and added another $150 to the build that wasn’t anticipated—such is the way with rebuilds and restorations.

The rifle came back completely unrecognizable … but in a good way. Tyler refinished the basic black scope mount in addition to the frame, and it couldn’t have been done better.

In a sense, it works on a very similar principle to the original falling block rifle that inspired this build. Technically, it’s just a single-action single-shot. Yet Tyler’s refinishing, Boyds’ furniture and the Talley rings with a Leupold Vari-X lend an air of old-world aristocracy to a very utilitarian and American-made rifle.

This was a fun build that took a couple of years to complete from start to finish. Part of that may have been supply chain issues, waiting on the services of the right gunsmith and finding a replacement hammer, but it was well worth it. The total cost of this project was a little under $1,700, about one-fifth of the price of the rifle that inspired this build.

The best thing about a Contender build is that the options are virtually endless. At one time, you could find just short of 100 calibers among factory offerings, custom shop models and, of course, wildcats. To do it these days on some of the more exotic calibers might take a bit of scrounging and searching gun shows, gun shops, estate sales and online auctions, but you can truly build a one-of-a-kind rifle or pistol if an extremely accurate single shot is what trips your trigger.

Custom Thompson Center Contender Build & Pricing:

Contender Frame: $200

Boyds Gun Stocks Nutmeg Stock & Forend: $160

21-inch Barrel: $150

Talley Case-hardened Scope Rings: $220

Talley Base: $60

Leupold Scope: $350

Refinishing: $350

Gunsmithing: $75

Replacement Hammer: $150

Sources:

Thompson/Center Arms: TCarms.com

Boyds Gun Stocks: BoydsGunstocks.com

Leupold: Leupold.com

Talley Rings: TalleyScopeRings.com

Tyler Gun Works: TylerGunWorks.com

Editor's Note: This article originally appeared in the September 2022 issue of Gun Digest the Magazine.

More Hunting Rifle Reviews:

- Back In Black: Marlin 1895 Dark Series Review

- Montana Rifle Company Junction Review

- Rossi R95 Review: Hands-On With The Trusty Trapper

- Bergara BMR Review: .22LR Tested

![Best Concealed Carry Guns In 2025 [Field Tested] Wilson Combat EDC X9S 1](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Wilson-Combat-EDC-X9S-1-324x160.jpg)

![Best 9mm Carbine: Affordable PCCs [Tested] Ruger Carbine Shooting](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Ruger-Carbine-Shooting-100x70.jpg)

![Best AR-15: Top Options Available Today [Field Tested] Harrington and Richardson PSA XM177E2 feature](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Harrington-and-Richardson-PSA-XM177E2-feature-100x70.jpg)