Want to buy a thermal scope? Here we discuss important considerations when shopping for one and go over the best models for helping you see what’s hot.

Thermal scopes are getting increasingly popular, so there are quite a few options on the market. How do you know what’s best for you? Which features will match your intended use? What models fall inside your budget?

Here we're going to go over what thermal scopes are, how they differ from night vision optics, what you should look for when choosing one and finally the best examples of thermal scopes you can buy right now.

Thermal Scope Development

A thermal scope is a compact thermographic camera that detects the infrared spectrum (IR) and displays the heat signature of objects.

Heat is a form of energy. Because it radiates outward, it is therefore also radiation! To detect it with the naked eye you need a special device capable of transforming these heat signatures into images, hence the thermographic camera.

The first thermal imaging equipment didn't emerge until the 1950s, and those were very large, very slow and could only generate a single image. Thermal imaging with mass sensor arrays was also developed for line scanning (like for detecting a missile launch) as part of national defense systems, such as the Yellow Duckling system used by the British.

The first portable thermal cameras emerged in the 1970s, initially for industrial uses (linemen, EMTs and firefighters were early adopters and current users) and later were repurposed for military applications. Sensor development began in earnest as solid-state (transistor) components became more common eventually culminating in increasingly useful and compact digital IR detecting devices.

Thermal Vision Vs Night Vision

Now, it’s important to understand that thermal vision differs from night vision.

Night vision devices—NVDs—don't detect heat, they amplify ambient light. NVDs convert photons (light particles) into electrons (electric particles) and create an image. Analog NVDs use cathodes and digital ones use a processor. However, because NVDs rely on some amount of ambient light to function, they also require an IR illuminator to work in total darkness.

Thermal cameras, however, do not require light. They have a far longer useful range (if powerful enough), and are functional in daytime.

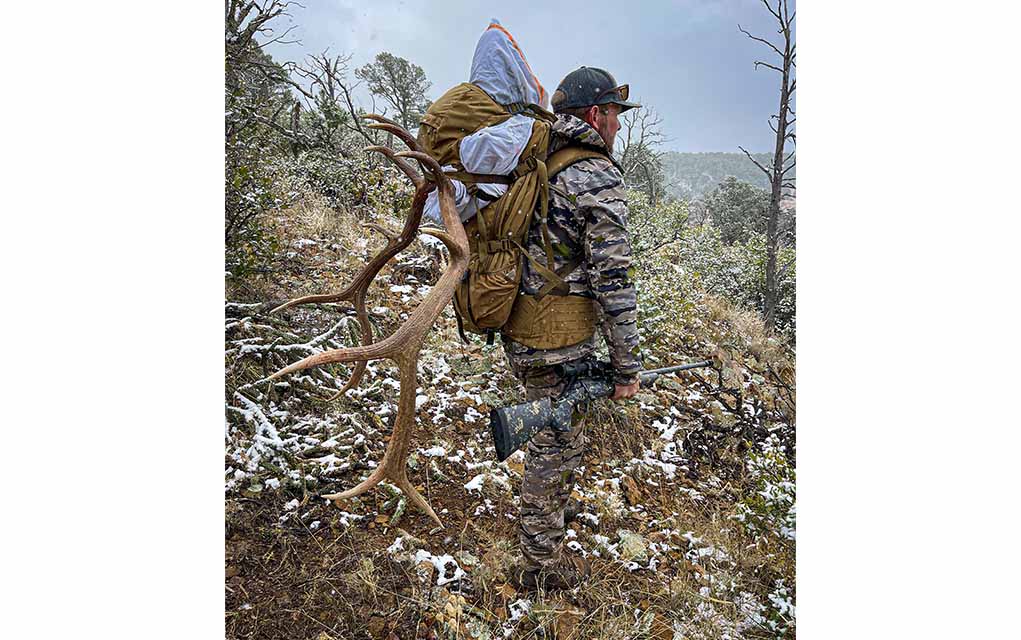

The military/defensive applications are obvious. For civilians, one of the most popular uses is for lawful night hunting.

Night hunting is illegal for most regulated game species. However, unregulated game species, such as feral hogs, are typically fair game (check your local laws first). In turn, thermal scopes are popular in feral hog-infested areas and will only increase in popularity as the problem spreads.

Thermal Vision 101

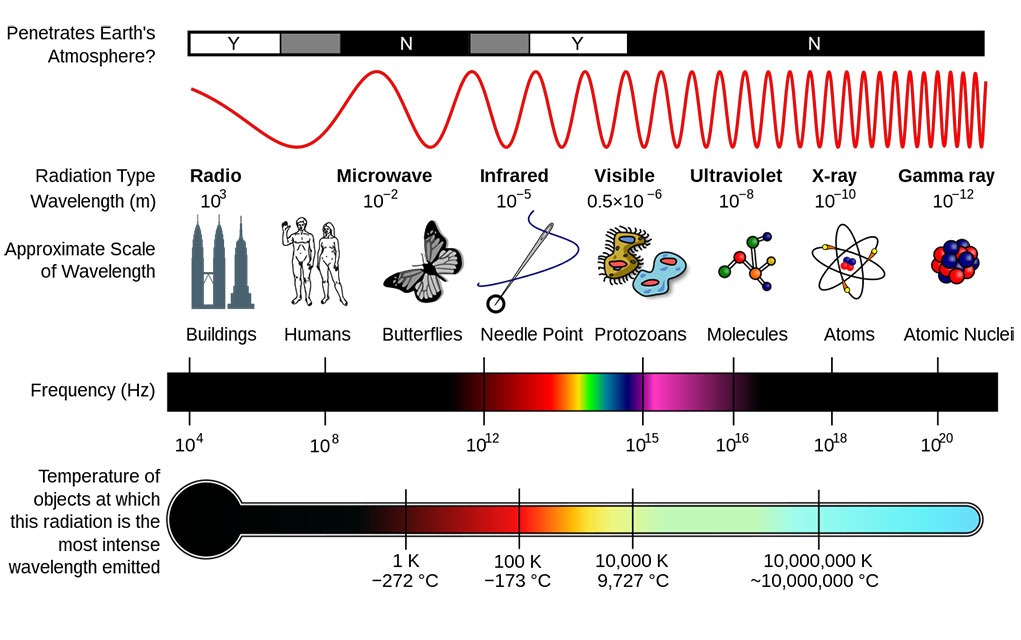

Light and other forms of electromagnetic (and other) radiation have a wavelength, a frequency. That wavelength determines color and visibility, just like how the frequency of a sound determines its pitch (A, for example, is 440 hertz) in music.

Visible light only makes up about 10 percent of the total electromagnetic spectrum. Ergo, normal cameras can't detect the other 90 percent.

Normal human vision picks up wavelengths between about 380 to 750 nanometers. The ends of the visible spectrum are violet in the 380 nm to 450 nm range and red in the 625 nm to 750 nm range. Light with a shorter wavelength than 380 nm is ultraviolet, and light with a wavelength of more than 750 nm is infrared until you cross into the higher (x-rays, gamma rays, etc.) and lower (microwaves, radio waves, etc.) ends of the spectrum.

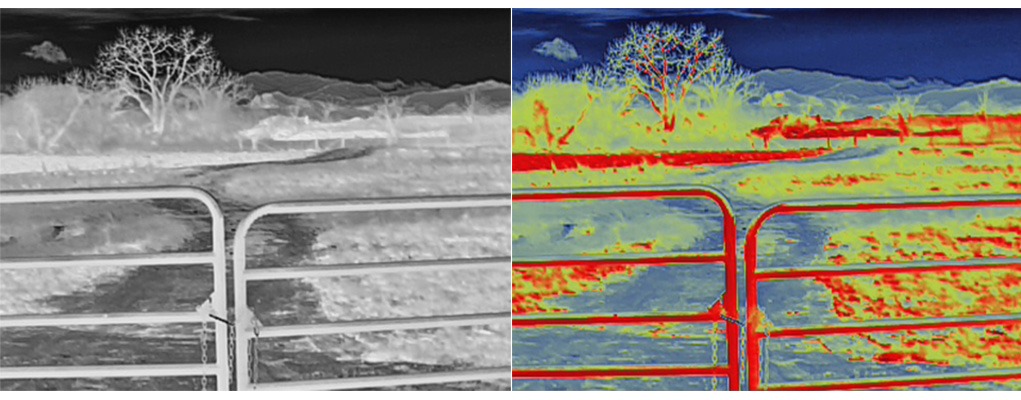

Thermal scopes (or any thermal imaging device) detect heat in the form of IR radiation and convert it into an image. The device interprets the wavelengths into into different colors and levels of contrast on the display to visually differentiate between the temperatures and shapes of objects.

There are different types of sensors used for various thermographic imaging purposes, but most thermal scopes (especially on the civilian hunting market) use Long Wave Infrared or LWIR sensors. The other two kinds, Short Wave and Medium Wave, have their uses but mostly outside of small arms optics.

Thermal Scope Features

A thermal scope, then, is simply a compact thermal camera with a reticle that can be mounted on a firearm. That said, the design, features and overall quality of the device all affect what role it will best be suited for.

Resolution

The heart of the optic is the sensor array and the display. A good sensor array is useless if the display can’t accurately show you what’s been detected, and a good display isn’t worth much if the sensors are underpowered in comparison. Both are required if you want to see an accurate depiction of the IR wavelengths you’re pointing the scope at.

The current industry standard for sensors is 12-micron pixel pitch sensor, but 17-micron pixel pitch sensors are becoming more common. As for the resolution, lower-end scopes tend to have 320×240 displays, 400×300 is mid-grade and 640×480 is what you find at the top of the market. Current U.S. military issue optics include devices like the AN/PAS-13B (by Raytheon) and Leonardo DRS INOD Block III. Both are cooled LWIR devices with clip-on (Picatinny rail) capability, 640×480 resolution and a 12-micron sensor. The L3Harris PAS-13G, a more compact version of the 13B, has a 17-micron sensor.

The point is that the higher the resolution, the sharper the image…but balance that with your use case. The more detail you need to see, the more important the definition quality is and the more you’ll need to pay for it.

Using a thermal scope for finding whitetails or hogs on a high fence hunt? 400×300 or a bit less will do you fine. If you’re an officer at a small department that has to purchase your own equipment? Target detection and discrimination are hugely important. Ergo, get the highest definition you can. Range is also something to consider, as the more magnification or zoom a scope has the better the resolution will need to be to clearly see objects at the higher levels.

Refresh Rate & Display Features

The refresh rate is also something to consider, as the higher the Hertz the faster it will show you what’s actually being detected.

Other important aspects to consider are the display features, but these vary between models and manufacturers.

Some will give you things like picture-in-picture, others won't, and whether that matters depends on how you plan on using it.

Some have Bluetooth capability, so you can link them to a phone app to capture or even stream footage, and some have the option to save multiple reticle configurations for different rifle/caliber setups.

Different scope models can also come with various color palettes, these give you different visual contrasts in temperature. The two most common types used for thermal scopes are black hot and white hot, but some may prefer more colorful options.

Other Thermal Vision Aspects

Some of the other attributes worth paying attention to are the typical things you should be aware of when it comes to rifle scopes.

Select the magnification range and field of view based on the range of hunting you're going to be doing. Stalking pigs on a Texas ranch? You don't need an 18-power scope or a Christmas tree reticle. Looking for elk on the next ridgeline so you know where to start your hunt tomorrow? Different story. A scope’s detection range and identification range are important to pay attention to here as well, but those are mostly determined by previously mentioned points such as sensor and display quality. If you need to detect or positively identify targets at further ranges, you’re going to need a quality thermal scope.

The final point worth thinking about is the battery life and the type of battery. Longer battery life is always better, but the importance of it depends again on how you’ll be using the scope. Batteries that can be quickly swapped for a fresh one are a great advantage for those who will be spending a long time in the field, but rechargeable batteries can be convenient for those who won’t be away from a power source for too long.

At the end of the day, all thermal scopes are expensive, so you’ll want to weigh your options and consider the level of quality and feature set that you need to do the job. Unfortunately, technology is pricey, so the further you need to see and the crisper you need the displayed image to be the more you’re going to have to pay.

The 5 Best Thermal Scopes

What are the best thermal scopes?

- Best of the Best: L3Harris Light Weapon Thermal Sight

- Best Dedicated Night Hunting Scope: Burris BTH35 V2

- Best Multipurpose Device: Trijicon IR-Patrol

- Best Budget Model: Sightmark Wraith Mini

- Best Thermal Red Dot: Holosun DRS-TH

Best of the Best: L3Harris Light Weapon Thermal Sight

Specs

Sensor Resolution: 640×480 ; 17 micron

Display Resolution: N/A

Refresh Rate: 30Hz

Optical Magnification: 1X

Digital Zoom: 1-2X

Detection Range: ~2,000 Yards

Battery/Run Time: Four AA ; ~10 Hours

MSRP: ~$15,000

Website: l3harris.com

Pros

- Best quality thermal imaging on list

- Uses common, easily swappable batteries

Cons

- VERY expensive

The Light Weapon Thermal Sight by L3Harris is a current military-issue optic. It can be used on its own or as a clip-on (with a QD mount) in front of an ACOG, Aimpoint Comp or Eotech.

When it comes to sensor technology, the LWTS is hard to beat. It features a 640×480 17-micron resolution and the display has a 30 Hz refresh rate. The advertised detection range is 1,800 meters and the unit is capable of 2x digital zoom. The average battery life is an impressive 10 hours powered by four AA batteries that can be easily swapped in the field.

Other features worth mentioning include its four integrated ballistic reticles, its RS-170 Real Time Video In/Out for remote viewing and image/video capture that can be downloaded to a computer.

The biggest downside of the LWTS is the price, as they’re typically listed in the $15,000 to $16,000 range. If you want one, check the used market first as you can sometimes find lightly used units sold for significantly less.

Best Dedicated Night Hunting Scope: Burris BTH35 V2

Specs

Sensor Resolution: 400×300 ; 12 micron

Display Resolution: 1280×960

Refresh Rate: 50Hz

Optical Magnification: 1X

Digital Zoom: 1-4X

Detection Range: >750 Yards

Battery/Run Time: USB Rechargeable ; ~5 Hours

MSRP: $2,799

Website: burrisoptics.com

Pros

- Good quality thermal imaging and features for price

- Can pair with Burris app

Cons

- Battery can only be recharged via USB

- Can't be used with a day optic

The Burris BTH35 V2 is a good pick for a thermal scope on a dedicated night hunting rifle, as it can’t be clipped on in front of a day optic like some other units on this list.

The BTH35 V2 has a 400×300 12-micron resolution with a refresh rate of 50Hz as well as 1-4x digital zoom and multiple color palette options. It can also pair with the Burris ballistic app to customize the reticle and subtensions to your rifle and load, and it has video streaming and image capture as well. One downside is the battery, as it can only be recharged by USB and the advertised run time is 5 hours at 25 degrees Celsius.

MSRP is $2,799, but they can be found for less.

Best Multipurpose Device: Trijicon IR-Patrol

Specs

Sensor Resolution: 640×480 ; 12 Micron

Display Resolution: N/A

Refresh Rate: 30Hz

Optical Magnification: 1X

Digital Zoom: 1-8X

Detection Range: N/A

Battery/Run Time: 1 CR123 ; ~2 Hours

MSRP: $6,047

Website: trijicon.com

Pros

- Good digital zoom capabilities

- Battery can be easily swapped in field

- Thumbstick control makes using in dark or with gloves much easier

Cons

- Poor battery life

Compact, light, and designed for military use in a multipurpose role. It can be mounted on a rifle as a dedicated scope, a clip-on with a day optic or mounted on a helmet as a monocular.

The IR-Patrol has a 640×480 12-micron pixel sensor array and a 60Hz refresh rate. It also has 1-8x digital zoom, multiple contrast modes and a thumbstick control for easier manipulation in the dark.

The only big downside is the advertised battery life of only 2 hours per battery, but it’s powered by a single CR123 that can be swapped in the field. It’s also expensive and the base model does not include a rifle mount so you will need to purchase that separately. MSRP starts at $6,047.

Best Budget Model: Sightmark Wraith Mini Thermal Riflescope

Specs

Sensor Resolution: 384×288 ; 17 Micron

Display Resolution: 1024×768

Refresh Rate: 50Hz

Optical Magnification: 2X

Digital Zoom: 1-8X

Detection Range: 2,000 Yards

Battery/Run Time: 2X CR123A ; ~4.4 Hours

MSRP: $1,699.97

Website: sightmark.com

Pros

- Very compact

- Good digital zoom

- Relatively affordable

Cons

- Less than stellar battery life

Sightmark's Wraith Mini packs a lot of features for the price tag in a compact form factor that works well for light modern carbines or hunting rifles with a Picatinny rail.

The Wraith Mini features a 384×288 resolution 17-micron sensor with 2x optical magnification and 1-8x digital zoom. Power comes from two CR123A batteries with an advertised run time of up to 4.4 hours in preview (non-video) mode. Onboard memory allows for multiple presets, which lets you swap the optic across rifles of different calibers, change reticles and contrast modes and even capture video and audio. The housing is aluminum and it’s rated up to .308 Winchester. It also has multiple color palettes and an advertised detection range of 1,280 meters. At under 7 inches long and 1.2 pounds, it doesn't add too much bulk to a rifle, either.

Best Thermal Red Dot: Holosun DRS-TH

Specs

Sensor Resolution: 256×192 ; N/A

Display Resolution: N/A

Refresh Rate: 50Hz

Optical Magnification: 1X

Digital Zoom: 1-8X

Detection Range: ~68 Meters (rumored)

Battery/Run Time: 2X 18350 ; ~12 Hours

MSRP: ~$1,600

Website: holosun.com

Pros

- Very small and light

- Can be used as a regular red dot

- Good refresh rate

- Relatively affordable

Cons

- Very limited thermal range in comparison to other models

- Not yet available

The DRS-TH is the thermal model of Holosun’s DRS series, and it’s perfect for modern carbines such as those .300 Blackout SBRs that a lot of folks hunt hogs with. The most interesting and novel feature of the DRS-TH is the thermal portion is displayed on an overlay, so it can be flipped down to allow the optic to function as a standard red dot.

The DRS-TH has a 256×192 resolution sensor, but the micron pixel pitch isn’t listed. That’s a bit low compared to most other thermals, but keep in mind that this is designed to be primarily used as a red dot and the 50 Hz refresh rate helps compensate for that. That said, it does feature up to 8x digital zoom as well. The optic includes Holosun's Multiple Reticle System (65 MOA ring, 2 MOA center dot or both) and either a Cross or T-style thermal reticle. Power comes from two 18350 batteries and the advertised battery life is 12 hours. Other features worth mentioning include its multiple color palette options and its on-board image and video recording.

The only hitch is that the optic is pre-order only at the time of this writing, though it’s anticipated to be released soon and the early reviews that have been published make it look quite promising. The DRS-TH will retail for around $1,600, but you're not going to find a similar thermal red dot from a reputable manufacturer for anywhere near that MSRP.

| Model | Sensor Resolution | Display Resolution | Refresh Rate | Optical Magnification | Digital Zoom | Detection Range | Battery/Run Time | MSRP |

| L3Harris Light Weapon Thermal Sight | 640×480 ; 17 micron | N/A | 30Hz | 1X | 1-2X | ~2,000 Yards | Four AA ; ~10 Hours | ~$15,000 |

| Burris BTH35 V2 | 400×300 ; 12 micron | 1280×960 | 50Hz | 1X | 1-4X | >750 Yards | USB Rechargeable ; ~5 Hours | $2,799 |

| Trijicon IR-Patrol | 640×480 ; 12 Micron | N/A | 30Hz | 1X | 1-8X | N/A | 1 CR123 ; ~2 Hours | $6,047 |

| Sightmark Wraith Mini Thermal Riflescope | 384×288 ; 17 Micron | 1024×768 | 50Hz | 2X | 1-8X | 2,000 Yards | 2X CR123A ; ~4.4 Hours | $1,699.97 |

| Holosun DRS-TH Thermal Red Dot | 256×192 ; N/A | N/A | 50Hz | 1X | 1-8X | ~68 Meters (rumored) | 2X 18350 ; ~12 Hours | ~$1,600 |

More Thermal Weapon Sights And Monoculars:

- iRayUSA Thermal Sights And Monoculars

- Burris Thermal Optics

- Night Optics SVTS Thermal Scopes

- The Leupold LTO Tracker Thermal Sight

- The Steiner H35 Nighthunter Thermal Monocular

![Best Concealed Carry Guns In 2025 [Field Tested] Wilson Combat EDC X9S 1](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Wilson-Combat-EDC-X9S-1-324x160.jpg)

![Best 9mm Carbine: Affordable PCCs [Tested] Ruger Carbine Shooting](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Ruger-Carbine-Shooting-100x70.jpg)

![Best AR-15: Top Options Available Today [Field Tested] Harrington and Richardson PSA XM177E2 feature](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Harrington-and-Richardson-PSA-XM177E2-feature-100x70.jpg)