The Makarov is a classic carry pistol, but there are a few things you can do to help bring it into the 21st century.

While not nearly as common as they once were on the hips of armed citizens, my concealed carry pistol is a Makarov. But to me, familiarity goes a long way, and what the pistol lacks in modern features it more than compensates for in time-tested reliability.

However, any pistol as old as the Makarov poses a challenge for those of us looking to take advantage of leaps in shooting technology since the gun was built. While there are hurdles to modern upgrades for such guns, they’re not out of reach … you just have to know the steps to turn a classic into a modern masterpiece.

Evaluating Shortcomings

Like many old pistols, especially military surplus models, the Makarov lacks in certain departments. While its mechanical accuracy is better than most would expect (it does have a fixed barrel, after all), the original sights are difficult to utilize. Tiny, black and a challenge to build a fast sight picture with, they’re less than ideal for a carry gun. Furthermore, the adjustable target sight found on Russian Baikal models isn’t any better.

As bit of a self-diagnosed Luddite—evidenced by my refusal to stop carrying a 70-year-old pistol design—I’m still aware of the advantages that red-dot sights provide. After shooting other red-dot-equipped handguns, I realized that getting an optic on my Makarov was the top priority. And while I was at it, I figured I’d see if I could improve the Soviet steel’s capacity, ammunition and holster, too.

Cottage ‘Gundustry’ Saves The Day

When trying to upgrade a gun as old as the Makarov, you quickly learn there are some major hurdles. Chief among them is the lack of companies willing to work on them. Most of the major outfits that offer custom slide-milling/adapter-plate work aren’t too keen on doing something so unorthodox and experimental.

So, the first lesson for upgrading vintage guns is that you’re going to have to research. A lot. Mine led me to 2C/ X Nihilo, a small company that advertised doing truly custom work. As a bonus, the company had previously mounted a red dot sight to a couple of Makarovs and a CZ 82.

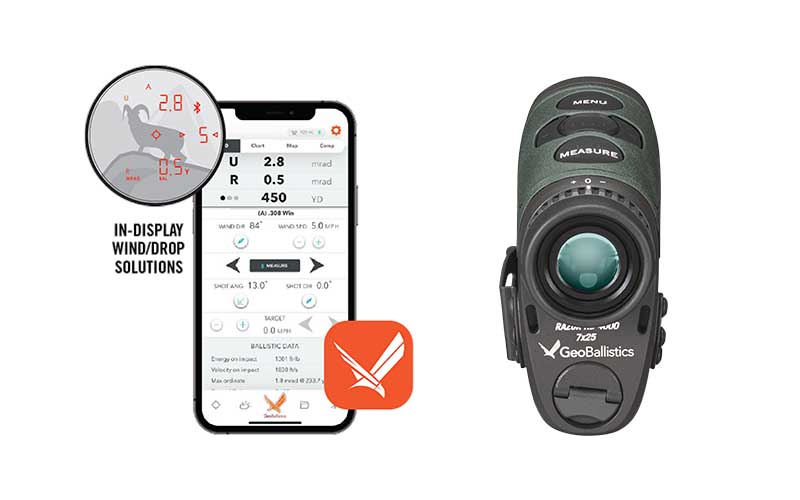

Tu Nguyen is the man behind the shop. He’s a Vietnamese immigrant who owns a small engineering firm that mostly does designing and prototyping for the biotech industry. And he also loves guns. Since he already had all the fancy machinery, he decided to start doing custom gunsmithing jobs out the back of his shop, too. After shooting off an email, 2C was quick to accept the job and it was time to ship them my slide and red dot sight: a Crimson Trace RAD Micro Pro.

As for the slide, I didn’t want to molest the original that came with my gun, so I bought a spare. Even though the spare I got was a Russian-made .380 ACP slide and my Makarov was a 9x18mm Bulgarian, they interfaced perfectly. The only real difference between Makarovs of each caliber is the barrel, making the slides universally interchangeable.

After sending everything to Nguyen, he was quick to get the work done. He essentially removed some more material from the rear of the slide with extreme precision, fabricated a custom adapter plate for my specific red dot and then put it all together.

After he got the plate anodized, the final product was ready and soon back in my hands. I couldn’t have been more pleased with the results: The red dot seamlessly integrated into the slide, so much so it looked as if that’s how it rolled off the line at Izhmash.

The cherry on top was the cost. 2C’s standard charge for this sort of work is $150 for the optics cut and $75 for the custom adapter plate. That’s a very reasonable price for top-end milling work.

A New Perspective

The results of Nguyen’s work at the range were as impressive as the aesthetics.

To zero the optic, I shot paper from a rest and progressively moved further back, to about 20 yards, until I was convinced the Makarov exceeded my accuracy potential. The groups were acceptably tight and consistent.

Since then, I’ve put at least 300 rounds through the setup without it losing zero. That was between two range sessions, with me carrying it concealed in between those sessions.

Target transitions with the upgraded pistol were just as good. After a bit of practice presenting and finding the dot, I’ve never cleared a plate rack faster: The benefits of this upgrade were immediately apparent.

As to the CT RAD Micro Pro, so far I’ve been very pleased. The 3-MOA red dot automatically adjusts its brightness according to ambient light conditions, and it detects motion to remain deactivated when not in use. My only true gripe is this: Without a way to manually override the auto-adjusting brightness, zeroing it on a sunny day proved difficult given the size of the dot at its highest setting.

The RAD Micro Pro also has built-in rear iron sights. They’d likely work fine on most conventional and contemporary optics-ready pistols, but unfortunately, they’re too high for the Makarov’s front sight. It’s not Crimson Trace’s fault, but it’s one downside to custom setups such as this.

Upping Capacity

With the new optic installed, I turned my attention to capacity next. For the Makarov, this required a new gun purchase.

There’s a lesser-known Makarov variant out there called the PMM (translated: Modernized Makarov Pistol) that was developed at the tail end of the USSR. Commercial variants were imported into the U.S. for a few years in the ’90s as the Baikal IJ70-18AH, and the gun’s most distinguishing feature is a 12-round double-stack magazine. Compared to an original Makarov’s eight-round capacity, this is a substantial improvement. The PMM is otherwise virtually identical to a standard PM besides its slightly wider frame to accommodate the new magazine.

I was lucky enough to stumble across a couple of rare PMM magazines at a gun show, so I had no choice but to get a pistol to go along with them as well. As mentioned previously, Makarov slides are interchangeable, so adding the red dot to the double-stackarov was as simple as swapping its slide.

Final Touches

As for accouterments for the souped-up Makarov, I was pleasantly surprised to find that Vedder Holsters offers a model for the Makarov with an optic cut. I picked up an IWB LightTuck with a claw attachment … and it fit both my standard PM and PMM like a glove. The claw also helps conceal the PMM’s slightly thicker grips.

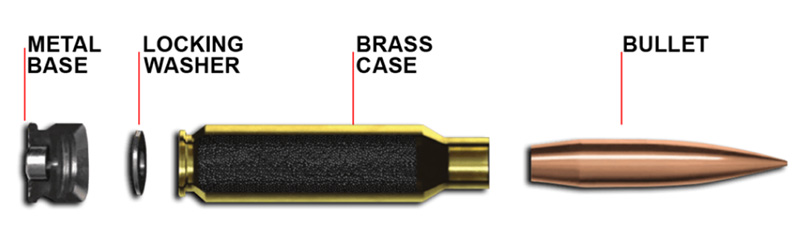

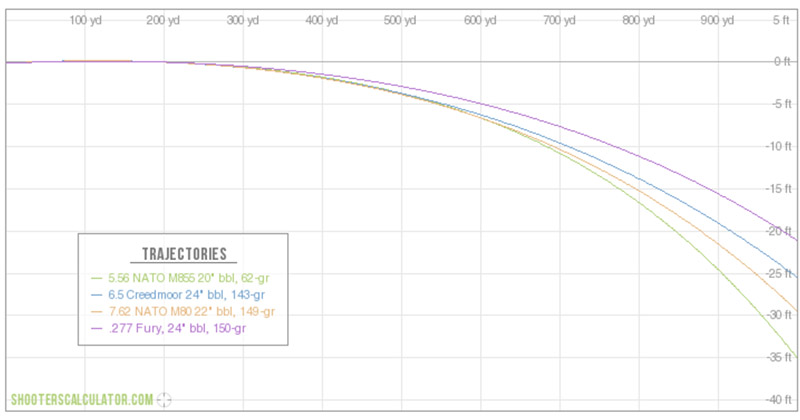

As for ammunition, while 9x18mm may not be as powerful as 9x19mm, it does pack a bigger punch than .380 ACP. I was previously carrying my Makarov loaded with Brown Bear hollow-points, but Hornady released a fresh batch of 9x18mm Critical Defense rounds just in time for my carry ammo to get upgraded, too. A 95-grain FTX bullet traveling at nearly 1,000 fps shouldn’t be underestimated.

Locked And Loaded

While I still don’t think that a standard Makarov is a bad carry gun, the effort I put into modernizing my own feels worth it. My Mak now has a red dot sight, four more rounds on tap and a Kydex holster to carry it all around in, all for a pistol that’s root design was finalized in 1951.

The rising tide of technology is bringing the firearms industry along with it, allowing companies like 2C to offer some incredibly niche services. No matter how odd your idea for a gun project may be, it never hurts to hit some Google searches and ask around.

Editor's Note: This article originally appeared in the 2023 CCW special issue of Gun Digest the Magazine.

More Classic Military Guns:

- Why The Mauser C96 “Broomhandle” Still Looms Large

- Nagant Revolver: Unique Relic From Behind The Iron Curtain

- M1917 Enfield: The Unofficial U.S. Service Rifle

- Browning Automatic Rifle: The Gun That Changed the Infantry

![Best Concealed Carry Guns In 2025 [Field Tested] Wilson Combat EDC X9S 1](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Wilson-Combat-EDC-X9S-1-324x160.jpg)

![Best 9mm Carbine: Affordable PCCs [Tested] Ruger Carbine Shooting](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Ruger-Carbine-Shooting-100x70.jpg)

![Best AR-15: Top Options Available Today [Field Tested] Harrington and Richardson PSA XM177E2 feature](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Harrington-and-Richardson-PSA-XM177E2-feature-100x70.jpg)