The unlikely tale of how laminate stocks went from curiosity to commonplace, changing the shooting world along the way — for the better.

How did laminate stock storm the firearms world?:

- Prior to 1987, there wasn’t a single American manufacturer that offered a wood laminate stock.

- Jack Barrett and his company, Rutland Plywood, changed this in the mid-1980s.

- Utilizing special epoxies, the company layered extremely thin veneers of birch to create stock blanks.

- In many cases, stock blanks consisted of 30 to 36 1/16” veneers.

- The advantage offered by laments are blemish-free material, greater strength and better action fit.

- Additionally, they do not swell or warp due to environmental conditions.

For those of you who might be either too young or too new to the world of firearms, the colorful wood laminated stocks you see in the catalogs of literally every rifle manufacturer are a fairly recent development. Prior to 1987, there was not a single wood laminated stock being offered by an American production rifle manufacturer. Today there’s not one that doesn’t offer several among its various sporter and varmint/target models. Seldom can a trend that has become so broad and pervasive be traced to a single company, but in this case it can: the Rutland Plywood Corp. of Rutland, Vermont, and its owner and CEO, Jack Barrett. Unfortunately, RPC burned to the ground in late August of 2014, but that doesn’t change the story.

Humble Beginnings

It was at the 1987 SHOT Show that Winchester, Ruger and Savage all exhibited for the first time examples of their flagship bolt-action rifles wearing laminated stocks machined from blanks furnished by RPC. It created quite a stir! My appreciation for laminates, however, goes back to the early 1960s; by then, I was stocking my own rifles using the shaped and semi-inletted stocks as offered by Reinhart Fajen, E. C. Bishop & Sons, and Herters, which were the largest retail sources at the time.

It didn’t take me long to realize after dealing with a couple of traditional walnut stocks that warped enough between the dry winter and humid summer conditions of Pennsylvania, which had them constantly changing zero, that there had to be a better, more stable stock medium. At that time, what few synthetic stocks that existed were crude at best, in their infancy technology-wise, and pretty much used only by the benchrest crowd.

Back then the most appealing stock to my eyes was the Regent by Fajen. It was a racy-looking thing with a high, straight comb line that was actually slightly higher at the heel of the butt than it was at the point of the comb. What made this stock look so streamlined was that the upper left quadrant of the pistol grip was not rounded off. In other words, in silhouette, the top line across the grip area was almost a straight line from the receiver tang to the point of the comb (Here is where a picture is worth a thousand words).

Anyway, the Fajen people offered the Regent in an all-walnut laminate of 5⁄16-inch laminations, which they turned from blanks purchases from a furniture manufacturer. That meant there were only six layers of wood in a typical stock, so the multi-layer look we see in today’s laminates was very subdued.

The Birth Of The RPC Laminate

By the time I became a full-time gun writer in 1970, I owned three rifles stocked in Regent laminates and wrote about why I liked them on a regular basis — a fact that did not go unnoticed by Jack Barrett. Jack was a gun enthusiast and hunter who, in the mid-1980s, had begun developing a birch laminate specifically for rifle stock applications. At that time, RPC had been in business for more than 30 years and was one of the largest manufacturers of specialty wood laminates and plywood for industrial use, so the technology and wherewithal were already there.

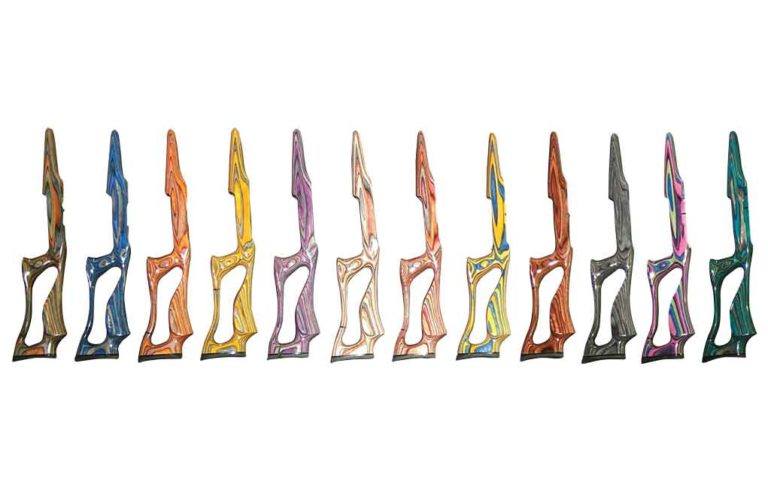

To make a long story short, after seeing several of my articles, Jack got in touch with me and invited me to visit his plant; that was in 1986 when they had just finished more than two years developing the special epoxies and production processes to make an absolutely stable, warp-free gunstock that would never de-laminate. Moreover, it was comprised of the thinnest possible layers of white birch — veneers actually, each only 1/16” thick. The result was a blank consisting of 30 to 36 individual layers of wood, depending on the stock style to be turned from it. Couple that with the ability to dye the veneers any color and assemble them in any combination, and you’ve got what we’ve all come to take for granted as the wood laminated stock.

How The Magic Happens

The actual process to arrive at a blank ready for shipment to firearm and stock manufacturers is a fascinating one. Logs are first debarked and cut to length — about 40 inches. These log sections are then placed in a huge steam room for a couple of days where they soften and become easier to machine.

Next comes the turning process that actually produces the veneers. The logs are placed on a lathe where they are spun at high speed against a huge blade. The logs, of course, are never perfect cylinders at the start, so the first few revolutions against the inward-moving blade come off as irregular sheets.

Once the log is trued up, however, one continuous veneer comes peeling off at about 15 mph. The spinning log is reduced to the diameter of a broom handle in less than a minute. As the sheet comes peeling off on a large conveyor belt, it passes beneath an optical comparator that triggers a vertical blade, which cuts out any section having knots, voids or other imperfections.

Once the veneers, which at this point are virtually wet to the touch, are cut to size — about 12×35 inches — they go into a huge conveyor oven. Because the sheets are so thin, by the time the veneers come out the other side, their moisture content has been reduced to just 4 to 5 percent, which is lower than a homogeneous stock can be dried.

The processes described thus far afford two more advantages over a single piece of wood. Because the 30-plus veneers that go into each stock are blemish free, that ensures that as the blank is machined into a gunstock, no knots, voids or other flaws will be revealed. With one-piece walnut stocks, the rejection rate for such “surprises” can be as high as 8 to 10 percent.

The next step is the coloring process, which is done by putting stacks of veneers in a huge autoclave where color dye is introduced and the atmosphere is reduced to a vacuum that enables the dye to fully penetrate each sheet. After coloring, all that remains is for the veneers to be run through rollers, which deposit a proprietary epoxy to each side, then stacked by hand in the desired color combination. From there they are placed in a gigantic, multi-layer hydraulic press with heated platens that accommodate 20 blanks at a time. The stacks are compressed under 20 tons of pressure, while the heated platens speed the curing of the epoxy.

The Laminate Advantage

As touched upon earlier, laminated stocks are not only highly distinctive and colorful, but are far stronger and more stable than one-piece stocks. You can, for example, take a wood chisel, orient it parallel with the layering of the veneers, and whack it all you want with a hammer; the stock will not split along a seam. I’ve also seen a laminated stock that was turned and treated by Boyds with its standard stock finish, submerged in a swimming pool for 5 days, after which there was no measurable swelling or warping.

Bottom line: A laminate is just flat-out better at being a gunstock than the traditional one-piece chunk of wood. Not only is it much stronger and stable, it has a tactile warmth about it that no synthetic can match. It feels like wood because it is wood. Me, I like them as much as ever.

Editor's Note: This article originally appeared in the April 2018 issue of Gun Digest the Magazine.

Next Step: Get your FREE Printable Target Pack

Enhance your shooting precision with our 62 MOA Targets, perfect for rifles and handguns. Crafted in collaboration with Storm Tactical for accuracy and versatility.

Subscribe to the Gun Digest email newsletter and get your downloadable target pack sent straight to your inbox. Stay updated with the latest firearms info in the industry.

![Best Concealed Carry Guns In 2025 [Field Tested] Wilson Combat EDC X9S 1](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Wilson-Combat-EDC-X9S-1-324x160.jpg)

![Best 9mm Carbine: Affordable PCCs [Tested] Ruger Carbine Shooting](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Ruger-Carbine-Shooting-100x70.jpg)

![Best AR-15: Top Options Available Today [Field Tested] Harrington and Richardson PSA XM177E2 feature](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Harrington-and-Richardson-PSA-XM177E2-feature-100x70.jpg)

One thing not mentioned in this article is that laminated stocks have one disadvantage:

THEY ARE HEAVY AS HELL – at least 2 times heavier than a homogenous wooden stock.

Think about that before you re-stock your favorite sheep rifle with a laminate stock.

No laminate stocks prior to 1987, the stock blank for my Remington 600 350 Rem. Mag. must have come from some really rare tree.

The Germans and Soviets started using laminated stocks for their military rifles just prior to or very early into WWII. That’s about a half century before the 1987 SHOT Show.