Affordable, classic and a performer, the Henry Big Boy is top of the heap when it comes to pistol-caliber carbines and rifles.

What makes the Henry Big Boy the best pistol-caliber long-gun:

- 20-inch barrel adds 300 to 400 fps of muzzle velocity to a magnum pistol cartridge compared to 4-inch barrel revolver.

- Heft eats recoil making magnum cartridge more manageable.

- Longer sight radius improves accuracy potential compared to a handgun.

- Cycling requires only two movements and does not require rebuilding a sight picture from scratch.

- Can shoot not only magnums, but the cartridges they’re based on.

- Nine models, three with carbine and rifle options and up to five chambering options, there are 44 Big Boy variations to choose from.

- Affordable compared to other fine pistol-caliber rifle in its class.

- One drawback, no loading gate.

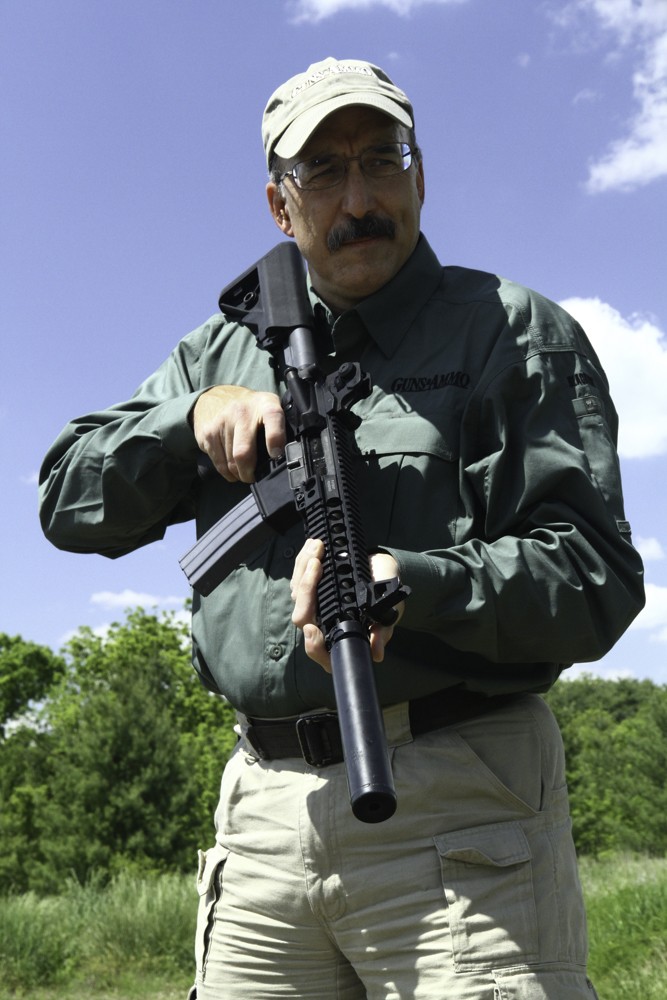

It’s a strange class of firearms. Pistol-caliber carbines and rifles, for the most part, are out on the fringes of the gun world — at least in their most modern form. Near refugees from a cyberpunk novel, many of the newest examples take cutting-edge beyond the pale and often times end up in plug-ugly territory.

Additionally, there’s the gnawing question, “Is it really worth it?” By and large, scaling up a pistol cartridge's platform (again in the most modern terms) is an exercise in diminishing returns. Capable plinkers and manageable home-defense options for those (perhaps through no fault of their own) are less than adroit with a handgun, overall they tend to offer few of the advantages of a legitimate rifle or full-fledged pistol. Might as well get a shotgun.

There is an exception for those willing to embrace an older, nonetheless potent and, dare I say, practical firearm. From Winchester’s Model 1866 and 1892 to Marlin’s 1894, shooters can get behind a long gun that legitimately upgrades a pistol cartridge’s performance, comes just shy of many semi-auto’s capabilities and remains as timeless as any firearm forged since the advent of smokeless powder. And in this particular sub-category of guns, it’s difficult to argue that any shine brighter than Henry Big Boy carbines and rifles.

Finding the sweet spot in price, function and gunny good looks, the Big Boy is hard to beat and arguably is the best when it comes to pistol-caliber long guns. Here’s why.

Magnum Chambering

Like a half-ton truck with a scooter’s engine, lack of power is the main gripe about pistol-caliber long guns. There’s simply not enough oomph to get most shooters excited. The Henry Big Boy (and most pistol caliber lever-actions for that matter) turn this argument on its ear.

Chambered in the most popular handgun magnums (and a couple black sheep too), the lever-actions pack more than enough punch to get the most diehard doubter to turn his or her head. And more so than the semi-auto pistol cartridges, magnums only shoot sweeter out of the likes of a Big Boy.

Give or take, a magnum round gains in the neighborhood of 300 to 400 fps of muzzle velocity jumping from 4-inch barreled revolver to an 18-inch long gun, according to data from BallisticsByTheInch.com. Some cartridges’ ballistics can become downright strophic with the extra bore. The .357 Magnum, for one, can easily top the 2,000 fps mark at the muzzle out of a 20-inch barreled Henry. Not only does this extend a cartridges' potential operational range, but also makes them more viable hunting options for everyday shooters. Out of a revolver, big-bore .44 and .41 magnums are handfuls. Shot from a Big Boy they’re kittens.

Shootability

Dovetailing off the last point, the Henry Big Boy opens magnum pistol cartridges to nearly every shooter. Given their longer sight radius and easy-to-use semi-Buckhorn rear sight, they make shooting a magnum round accurately a much simpler affair.

However, what they do to recoil is perhaps the more important aspect of the Henrys. Big Boys run from 7-pounds flat in the All-Weather Model to just shy of 9-pound in a model such as the Classic. Heft and a buttstock, for the most part, reduces a magnum's kick to a mere suggestion of what it is out of a handgun.

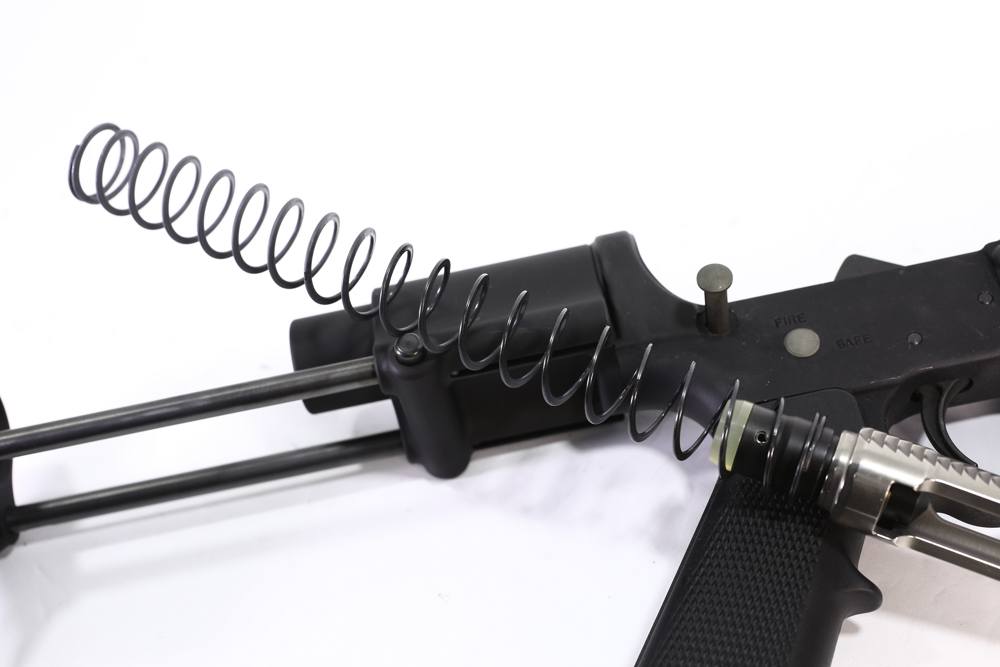

Finally, of all non-semi-autos, lever-actions are the simplest to shoot quickly without losing accuracy. Given you never have to move your head when cycling the rifle, you never have to rebuild your sight picture from scratch. Additionally, it takes only two motions, compared to a bolt-action’s four, to chamber a fresh round in a lever-action.

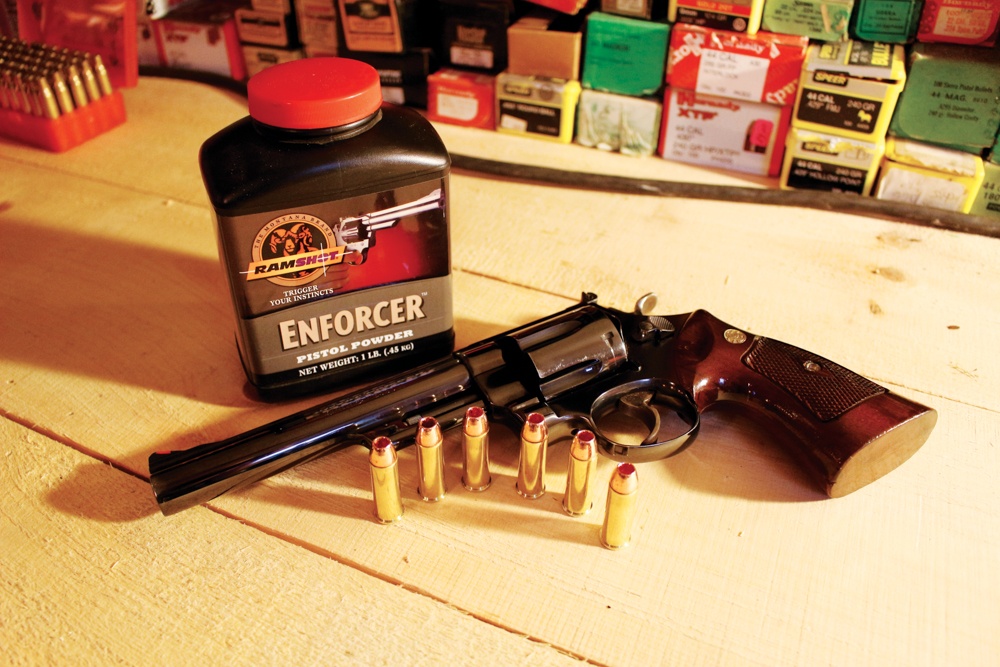

Ammunition Options

Who doesn’t like options? This line of Henry rifles gives you plenty of them if you buy in magnum. The great thing about the hot-rods, the cartridges they’re base on work in the rifles as well. In turn, if you buy a .357 Magnum Henry you also get a .38 Special, the .44 Mag a .44 Special, and the .327 Fed. Mag. (Steel, Classic and Carbine models) a .32 S&W Long and a .32 H&R Mag. Hard to beat.

The .41 Mag. and .45 Colt are a bit trickier, given they don’t have commercial cartridge counterparts — obvious in the second case, since the cartridge isn't a magnum. Though, there’s a case it doesn’t hold back the latter — for handloaders at least — given you can cook up nearly two-cartridges worth of rounds for the venerable .45. Everything from temperate target and plinking rounds to blistering hot and hard-hitting hunting options. Either way, Big Boys have you covered across the board.

Selection

Up to this point, one could argue you aren’t getting anything out of a Henry you wouldn’t out of a Winchester or Marlin. But selection is where the Big Boy starts pulling away. There are nine models of the pistol-caliber rifles and carbines and every one of them comes with a minimum of three chambering (.357 Mag./.38 Spc., .44 Mag/.44 Spc., .45 Colt). A few, such as the brass-receiver Classic, have five caliber options. Additionally, the Color Case Hardened, Steel and Special Edition II have both rifle and carbine variations. A good dilemma, you potentially have 44 Big Boys to sift through before you find the one that’s right for you.

Affordable Class

Winchester puts up a pretty good fight in this category, however, Henry wins out. First off, Henry is the master of the copper and zinc alloy we call brass and nothing shines quite a brightly as their receivers fresh out of the box. Furthermore, the company has a good eye for walnut, which in all models goes a long way in giving their guns soul.

Secondly, and perhaps more weighty, the affordability of a Big Boy can’t be beaten. The line starts at $893 (MSRP) with the Steel Model, a couple hundred dollar less than the most affordable 1892. And if you want some of the classic accouterments — octagon barrel, engraving, etc. — the Big Boy grows in price, however, stay extremely competitive compared with anything in is class. Is there another brass-receiver rifle with scrollwork, outside the Big Boy Deluxe Engraved II, that runs less than $2,000? To top it all off, all Henrys are completely American made — which still counts (or should) for something, at least in the gun world.

Devil His Due

Prattling on about the Henry Big Boy, you’d think there was nary a chink in the line’s armor. However, there is one aspect of its design that may turn some potential fans off and I would be remiss not discussing. Unlike Winchester and Marlin's pistol-caliber long guns, the Henry’s do not have a loading gate. Small in the scheme of things, it does make reloading more arduous (less so than an 1860) and topping off the magazine a no go. With Henry, reloading is purely accomplished through the guns' tubular magazine. Never wrestled with one before? I assure you it’s not a grease-lightning affair.

That said, the Henry Big Boy rifles have a 10-round capacity and the carbines 7-rounds; practically speaking that’s more than enough on tap to tackle most any job — even the vast majority of self-defense situations shy of a battalion assault. A bothersome aspect, perhaps. A deal breaker, by no means, considering everything else the Henry Big Boys bring to the table.

![Best Concealed Carry Guns In 2025 [Field Tested] Wilson Combat EDC X9S 1](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Wilson-Combat-EDC-X9S-1-324x160.jpg)

![Best 9mm Carbine: Affordable PCCs [Tested] Ruger Carbine Shooting](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Ruger-Carbine-Shooting-100x70.jpg)

![Best AR-15: Top Options Available Today [Field Tested] Harrington and Richardson PSA XM177E2 feature](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Harrington-and-Richardson-PSA-XM177E2-feature-100x70.jpg)