Looking to start a CCW training regimen? Have a plan and take one bite at a time.

In 2019, Jack Wilson used his concealed handgun to stop a bad guy in a church. Reportedly, the head shot that saved the congregation was taken at about 50 feet. More recently, Elisjsha Dicken saved more citizens when he took out a shooter in a mall at a reported 40 yards. As a result of instances like these, many have taken a page out of Jeff Cooper’s book and created training drills to replicate these real-world scenarios.

There’s nothing wrong with this, especially since the shots taken in both instances were a bit farther than what’s commonly associated with civilian shootings. However, conducting these drills aren’t the best way to train with your defensive handgun.

It’s About The Basics

Yeah, I guess it’s cool to say you “did the drill” and maybe even shot as well or better than the “Good Samaritan” the drill has been named after. However, the only way you’re going to be good enough to perform the drill to standard is by executing the basics of shooting. And, as boring as it might sound, the basics are what you should be practicing.

What are the basics of the defensive handgun? Well, it always starts with safety, and it always ends with proper maintenance and care of your firearm. If you can’t handle a firearm safely, and if your firearm isn’t in good working order, it might not matter how well you can shoot.

Next, you have gun handling and marksmanship. These are the skills you need to practice and master to be successful in a gun fight. Tactics matter, too, but they should only be addressed once you have a solid shooting foundation to work from.

Make A Plan

Haphazardness isn’t a plan. Just going to the range and banging away, while it might be fun, is not how you get better. The best way to get better is to start with a notebook or logbook that allows you to schedule your CCW training and keep track of your progress. A logbook like this could also be handy if you’re ever taken to court; it’ll show your methodical dedication to safe gun handling and self-defense.

The next thing you need to do is establish a CCW training program. The program you select will vary a great deal based on your skill level, and you might need to attend a training school—or at least shoot with a qualified instructor—to determine the areas you’re good at … and the areas you need to work on.

The training plan should be two pronged: It should include sustainment training for what you already do well, and it should include the additional skills you want to develop. As you progress in skill, your training plan should progress, too. You need to set goals, continually strive to meet them … and then set new goals.

Dry Practice And Live Fire

Don’t make the mistake of thinking that live fire is the only way you can practice or train. Dry practice—as boring as it might seem and is—is one of the most important aspects of firearms training. And, you can dry practice almost every skill you need to work on. You can dry practice drawing your handgun, reloading your handgun, manipulating your handgun and shooting your handgun. A training plan without dry practice can be effective, but what it will most assuredly be is a waste of money; ammunition is expensive.

Just as important is incorporating dry practice with live fire. When you’re at the range conducting live fire, intermingle dry practice. Let’s say, for example, you’re working on single shots from the holster. You’ll probably want to do this at least 25 times with live ammo. However, before you start with the live ammo, dry practice the process five to 10 times. Also, after every five to seven live-fire repetitions, again insert several dry practice runs. These dry practice repetitions intermingled with live fire are a great opportunity to slow down the process and look at each step.

One Bite At A Time

Regardless of whether you’re conducting a dry practice or live-fire training session, you must approach defensive handgun weaponcraft like you’re eating an apple—one bite at a time. If you need to work on your draw from concealment, then work on that.

Don’t confuse the training by trying to improve that skill while also working to get better at reloading or firing multiple shots fast. You master the basics of the defensive handgun one bite at a time, which is the same way you get to the core of the apple.

Measure Your Performance

Another good aspect of any CCW training plan is to have a benchmark of performance that you at first strive to meet, and then later try to exceed. This is where the logbook comes in handy; it allows you to keep track of how well you’re doing. If the logbook indicates you’re not progressing, it might be time to seek professional help. This benchmark should be a self-defense-style drill you conduct at the beginning and at the end of each training session, regardless of what you train on in between.

This is where the life-like scenario drills—such as the El Prez, Mozambique or Dozier—come into play. The same is true for the Jack Wilson or Dicken Drill. These drills aren’t so much CCW training drills; they’re evaluation drills to determine your capabilities, and identify the basic marksmanship skills you need to work on.

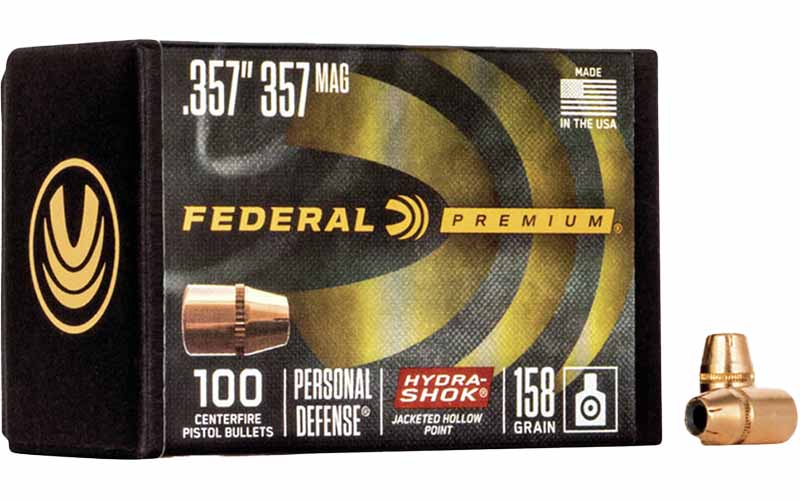

A benchmark drill is also a great time to test fire carry ammunition. By conducting it before and after a training session, you’ll test your handgun’s clean and dirty reliability with the ammo you expect to use to save your life. A box of 20 carry rounds should last you through four or five training sessions. The more training sessions you complete with the carry ammo without a stoppage increases your trust in that load and proves its compatibility with your carry gun.

Don’t Overdo It

One mistake that many shooters make is trying to shoot too much at one time. While taking a week-long self-defense handgun class at Gunsite Academy, you’ll probably shoot about 1,000 rounds or a bit more. During a five-day class, that works out to about 200 rounds per day. It’s set up that way because most shooters began to lose focus and get tired after about 200 to 250 rounds. And that’s under the tutelage of, and pace provided by, a competent instructor.

By incorporating dry-fire practice with your live-fire practice, you get the advantage of more trigger pulls and/or repetitions without excessive stress, and the added expense of more ammunition. At first, limit your live-fire sessions to about 100 to 150 rounds and make a concentrated effort to make every trigger pull count. In other words, don’t do mag dumps or ring steel just for the hell of it.

Rest is also important. Don’t step up to the line and fire all the rounds you’ve set aside for live fire at one time. After every 15 to 25 rounds, take a break, hydrate and think about your performance. This is a good time to make notes in your logbook and consider why you might be performing well … or poorly.

Tools Of The Trade

There are some tools that can help make your training sessions more enjoyable and rewarding, and this is especially true if you’re conducting all your training by yourself.

Smartphones can be a great tool when trying to master any physical activity. I coached high school soccer for five years and frequently used the video feature on my smartphone to illustrate to players things they were doing wrong. When my son was learning to long jump, we slow-motion videoed his jumps to critique his performance. Not only did he win several meets, but in his senior year, he set the school record. Set your smartphone up on a tripod and slow-motion video yourself while training. Then, watch the video to look for the mistakes you’re making.

A shot timer is also a great training tool. Though some trainers don’t like shot timers because they tend to make shooters go too fast to learn, I believe they’re fantastic if used correctly. In training, a shot timer should be used to measure how long it takes you to conduct a skill or drill correctly. Your goal is then to work to decrease that time. You’re already using a target to evaluate your accuracy; the shot timer is just a tool that’ll allow you to evaluate how you’re spending your time.

Laser trainers have become popular for dry practice. Though I don’t believe they’re necessary for successful dry practice, I’m sure they add some spice to the process. Some laser trainers are very simple and just flash a dot on the target. Others can be combined with targets or your smartphone to record each shot. Since most laser trainers are inserted into the barrel of your handgun, they do have the potential to make dry practice safer.

For dry practice and even for live fire, dummy rounds are a must. During dry practice, they help you maintain safety, and during live fire, they help you replicate stoppages. Dummy rounds are very affordable and well worth the money when you consider the safety and training value they can provide. You can tell how serious a shooter is about training by asking how many dummy rounds they have.

Also, targets matter. From a self-defense training standpoint, the targets can be very rudimentary. In some cases, a full sheet of copy paper works. In other instances, a sheet of copy paper folded once or twice will work, too. At other times, a simple dot on a sheet of paper is sufficient.

However, there’s a mindset element at play here. The adage to “train the way you intend to fight” has merit and applies to the conduct of your training as well as to the targets you shoot at. Life-like torso targets add realism.

Build A Foundation

The most important part of training with a defensive handgun—or any firearm, for that matter—is to build a solid foundation. This is extremely hard to do on your own because the unexperienced don’t understand what that foundation needs to support.

Without question, the best way to build this foundation is by attending a reputable training course, and there are none better than the Gunsite Academy 250 Pistol Class. The good news is that now Gunsite offers CCW training in multiple locations across the United States. I’d suggest anyone serious about the defensive handgun start there before you end up building a structure on a foundation that won’t reliably support what it needs to.

Editor's Note: This article originally appeared in the 2022 EDC special issue of Gun Digest the Magazine.

More On CCW Training:

- Video: Target Transition Training With The Dot Drill

- The Shot Timer And Defensive Handgun Training

- Gun Digest’s 10 Best Shooting Drills And Firearms Training Posts

- MantisX: Simple And Effective Training

- Video: Is A Full-Sized Pistol The Best Training Option?

![Best Concealed Carry Guns In 2025 [Field Tested] Wilson Combat EDC X9S 1](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Wilson-Combat-EDC-X9S-1-324x160.jpg)

![Best 9mm Carbine: Affordable PCCs [Tested] Ruger Carbine Shooting](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Ruger-Carbine-Shooting-100x70.jpg)

![Best AR-15: Top Options Available Today [Field Tested] Harrington and Richardson PSA XM177E2 feature](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Harrington-and-Richardson-PSA-XM177E2-feature-100x70.jpg)