We discuss the history of the famous FAL, also known as the Fusil Automatique Leger or Light Automatic Rifle.

Post-WWII, the West had a problem. The Europeans, having paid attention to the recent fracas (especially the Eastern Front), had developed new less-robust service cartridges and rifles for them. The problem? The Americans and their insistence on retaining a 1,000-yard cartridge. All the Euro efforts at lightweight, compact rifles with low recoil and bullpups (we’re looking at you, England) were out the window. The USA was paying the bills, and the USA was going to get what they wanted, cartridge-wise.

Deuidonne Saive, head designer at FN, modified his excellent (but already retro, even in the late 1940s) SAFN, the FN-49, to make it what NATO needed: Out went the fixed 10-shot magazine for detachable 20-shot magazines; out went the wood stock and in came plastic; out went the regular contour and in came a pistol grip.

The end result by 1953 was the FAL.

The Free World’s Right Arm

The FAL is a gas-operated, piston-driven, self-loading rifle, and it ended up being chambered in 7.62 NATO. The gas system is simple and straightforward, with a gas port in the barrel tapping gas out of the bore to hit the end of the piston. The piston slaps the bolt carrier, and after the carrier has moved, the FAL piston is returned forward by its own spring.

The carrier is a chunk of steel that cams the bolt up, then carries it back. Once fully back, it’s then driven forward by the action spring (contained in the stock in the non-Para version) to strip a round out of the magazine and cam the bolt down to lock it in place.

The FAL is not a turning-bolt design, as was the Garand and its successor, the M14.

The FAL is made of two main assemblies, the upper and lower receivers. To disassemble, unload and remove the magazine. The magazine lever is on the left side, forward of the trigger guard.

Press the takedown lever on the left rear of the receiver back (or down on some variants) and hinge open the rifle. Grab the top cover and slide it out of the upper receiver. Now, pick up the tail of the carrier and slide it and the bolt. On the hinge point, you’ll see a large-head screw with a slot in it. It’s as simple as unscrewing the hinge and pulling the two parts out (one to each side) while keeping the two receiver assemblies under control.

The gas system is adjustable. The gas port is a direct-to-air design, and the adjustment is done with a ridged nut on the gas block. The nut is machined with the top as a spiral cut, so as you adjust it, you cover or uncover more of the gas port bleed hole. More bleed, less gas to the piston; less bleed equals more gas to the piston. You adjust it by cranking it wide open and loading a single round.

Fire.

Does the bolt lock open? No? Click in a notch and repeat. Continue until the bolt locks open and then add one more click. What you’ll find is that your FAL (should you be so lucky) will work with pretty much everything at the setting you find with the first ammo you try.

Worldly Influence

Back in the 1970s and 1980s, the FAL was the Holy Grail of exotica small arms, the lust desire for survivalists, the rifle with enough panache to box up and sell. And a price to match. In 1980, the list price for an FAL was $2,000. Adjusted for inflation, that’s $7,580 today. A Colt AR-15 was $340 back then, and an HK 91 was $390.

Assuming you had 2 grand to spring for one, finding one would have been difficult. I was working gun shop retail then and walking local gun shows every weekend, and I do not recall ever seeing one—period. In fact, the first one I saw was when our gun club treasurer brought his to the club to shoot in his first 3-gun match. When he found out it was not at all competitive—and kicked him silly (he was maybe 5 feet, 7 inches and 140 pounds soaking wet)—he traded it at the next gun show for a Colt HBar and a literal trunkload of ammo.

The FAL was always a rarity in the U.S. until the “Great Parts Kit Era.” The initial imports were done from FN through Browning, and like other FN products, the markup was ferocious. There was a period when Century was importing parts kits and building up rifles, as they had done with so many other military rifles. Springfield Armory imported Brazilian parts, and rifles, as their SAR-80.

While literal boatloads of AK parts kits were being imported in the early 2000s, there were also large numbers of FAL parts kits brought in, just not as many. They were kits for two reasons. One, the importation of military arms had been restricted by the various “assault weapon” bans. And two, most FALs were select fire. You may read that the British L1A1 wasn’t select fire … well, yes and no.

The L1A1 was made exactly the same as select-fire FALs, but in the receiver opening for the auto sear and such, the British installed a bolt-lock setup that kept it from firing with the bolt only partially locked. In the words of the MOD Museum staff I’ve talked to about this, “Put in the full-auto parts and it runs full auto.”

Oh, and the British changed one other big thing: You’ll read about “metric” and “inch pattern” FALs. As far as the dimensions are concerned, both are mostly the same, and details are close enough to not matter … except for the magazines.

The metric mags use a stabbed-out lip on the front as a latching tab. The British replaced that with a soldered-on steel lip. Why? Because they wanted to be able to use L1A1 magazines in the LMG L1A2 (a heavy-barreled L1A1), and in their modified Bren guns, and the metric stab-lip wasn’t up to the task.

Oh, and the British also adopted the folding charging handle, from the Para version, for their fixed-stock FALs.

Parts kits had to be built on new receivers, which was a task a lot more difficult than bending flats to make AK receivers. Upper FAL receivers (the serialized part) are machined forgings (or in some replacements a casting), and it must be done right. Parts kits also had to have enough imported parts replaced to be “922r compliant,” which meant a handful of U.S.-made parts.

There Are Many Like It, But…

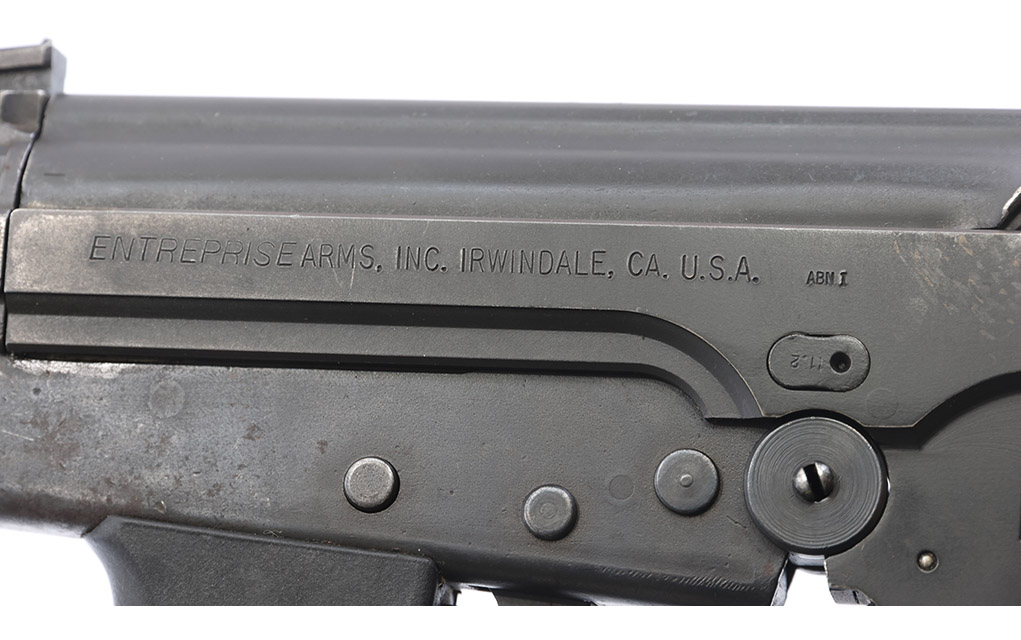

My FAL is an L1A1 parts kit built up on an Entreprise receiver. The history there is that the early receivers (mine seems to be) were good, but QC faded away, and the later ones were simply parts-holding anvils. Mine was assembled without the carry handle (something I’ll have to correct).

The FAL was built with a replaceable locking shoulder, so headspace could be adjusted and assembled correctly, and this is a detail that was apparently overlooked in some homebuilt FALs. (Mine, again, came out correctly.) Parts are getting scarce, but you can still have the headspace corrected if yours needs it, along with some other details.

The hard part for me was magazines. The FAL magazines have never been as available as AR or AK mags, and the inch pattern ones are even scarcer than metric mags. I considered myself lucky to have scored a bunch of them at $40 each, even though some were dented, and I’ll have to lift those dents.

The FAL is not a compact rifle. It’s 43 inches long, weighs more than 9 pounds and each magazine, holding 20 rounds, when fully loaded is 1 pound, 12 ounces by itself. If you are headed out on patrol with an FAL and seven magazines (140 rounds total), you are hoisting about 20 pounds of personal ordnance. This is not an exercise for those who have not been eating their Wheaties.

Recoil is what you’d expect, except more. Despite its weight, the FAL comes back at you. This is due in part to the mass of the bolt and carrier bottoming out in the receiver. The Para model, with its folding stock, uses a different recoil system, contained completely in the upper receiver (standard FALs are as common as dirt, compared to the rarity of the Para FAL).

Yes, you can rebuild an FAL into a Para model, but it requires a complete recoil assembly parts swap, as well as the stock. Assuming you could even find the parts now, it would cost about as much as just buying a Para. But darn, they are cool.

I’ve got one of those as well, a DSA build. And speaking of my DSA, a word about the parts kits: avoid the Indian ones. If you stumble across an FAL parts kit, you can still get it built, as DSA does offer upper receivers as well as built rifles.

The Indian parts are not to spec. When I arrived at DSA for the build for an article, one Indian part after another had to be rejected as out-of-spec, and often so out that it couldn’t even be modified, shimmed or altered to fit. I think by the time we were done, the resulting Para had two or three original parts—total—in it. That’s the risk you run.

Running an FAL is fun, and assuming you can handle the length and weight, it certainly delivers. Mine has a muzzle brake on it, part of the 922r compliance build, and it also takes a couple of inches off the original length as well as keeping the muzzle down. The original flash hiders were even longer than the ones you’d see on an M14/M1A.

In the service life of the FAL, it was adopted by something like 75 countries, and produced under license in half a dozen of those countries. But not the United States. Why? Basically, the fix was in, the M14 was going to replace the Garand, and when it came time to test the M14 side-by-side with the FAL, the testers knew they had to make the M14 the winner.

There are a lot of rifles that will get you some attention at the gun club, or on the firing line at the range you frequent. But none of them, short of something in .50 BMG, or belt-fed, will get the crowd an FAL will garner. It recalls the Falklands War, the Rhodesian Selous Scouts, Israelis in the desert fending off Egyptian-armored columns and any number of movies made about mercs. (Every bar I walked into on the Falklands had a captured Argentine FAL up on the wall as a trophy.) Even in a plain-Jane formal black, it’s an eye-catching rifle.

The drawbacks are its cost and the shrinking supply of spare parts. The advantages are that it’s an all-steel rifle, and about the only part that will ever wear out is the barrel, which can be replaced. If the time ever comes when there are no more surplus barrels to be had, a competent gunsmith with a big-enough lathe can make a replacement barrel for you from a barrel blank.

It won’t be cheap, but then again, nothing about the FAL ever was.

FN FAL SPECS:

- Type: Semi-auto gas-operated rifle

- Caliber: 7.62 NATO

- Capacity: 20+1 rounds

- Barrel: 21 inches

- Length: 43 inches

- Width: 1.3 inches

- Height: 7 inches

- Weight: 9 pounds, 6 ounces

- Trigger: 5 pounds, 7 ounces

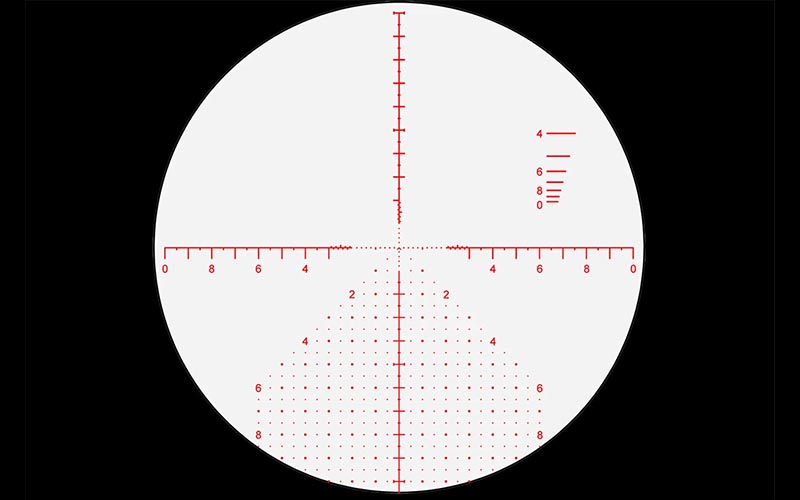

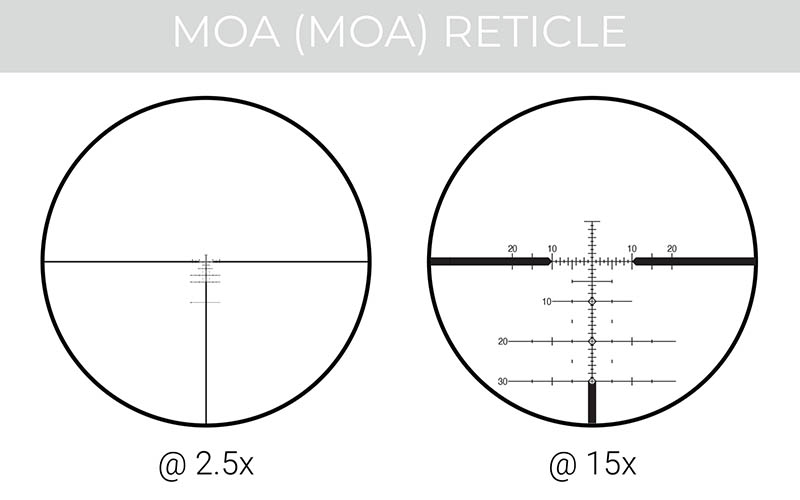

- Sights: Blade front, aperture rear

- Grips: Polymer furniture

- Finish: Black oxide, black paint

- MSRP: Expensive, but worth it

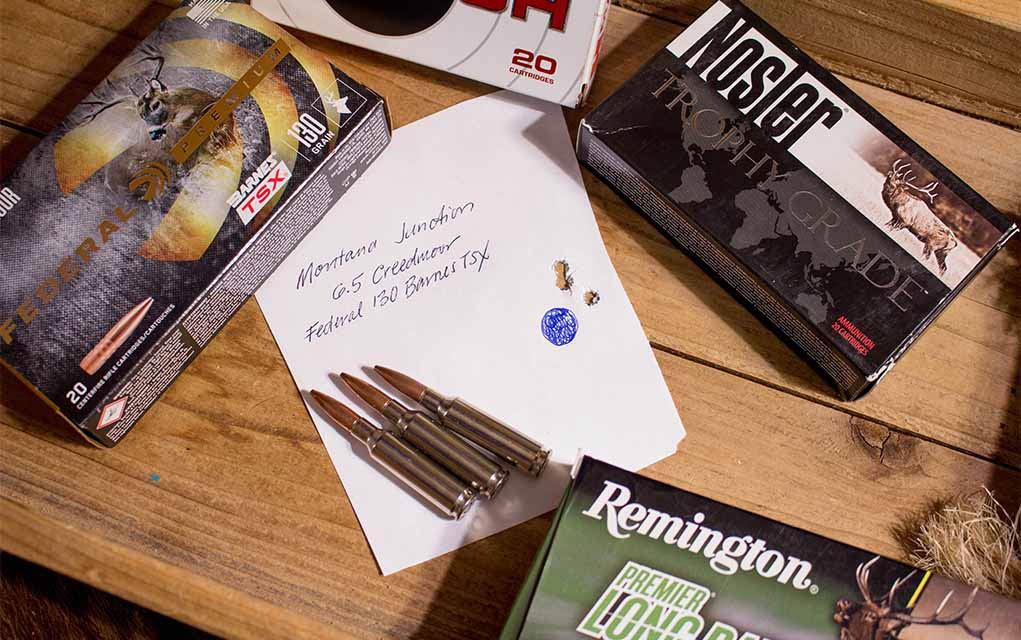

CHRONOGRAPH DATA

| Ammunition/Type | Bullet Weight (Grains) | Velocity (FPS) | ES. | SD. | Accuracy Average (Inches) |

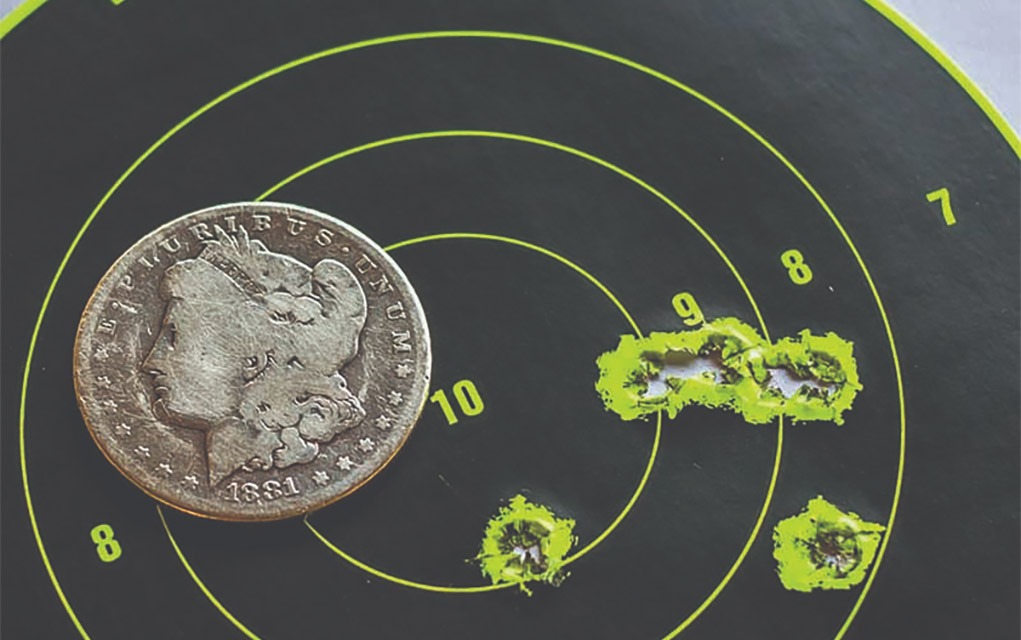

| RG69 (Radway Green arsenal), British surplus FMJ | 147 | 2,666 | 39 | 14.8 | 2.5 |

| REM-UMC FMJ | 150 | 2,725 | 57 | 25.7 | 1.9 |

| Federal M80 ball, FMJ | 149 | 2,781 | 19 | 8.8 | 2.1 |

Editor's Note: This article originally appeared in the July 2024 issue of Gun Digest the Magazine.

More Classic Cold War Battle Rifles:

- The FN-49: The FN FAL's Grandather

- New Production DSA FALs

- Roller-Locks Go Mainstream: The CETME Model 58

- The H&K G3 :The Most Successful Battle Rifle

- What To Know When Buying A G3

![Best Concealed Carry Guns In 2025 [Field Tested] Wilson Combat EDC X9S 1](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Wilson-Combat-EDC-X9S-1-324x160.jpg)

![Best 9mm Carbine: Affordable PCCs [Tested] Ruger Carbine Shooting](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Ruger-Carbine-Shooting-100x70.jpg)

![Best AR-15: Top Options Available Today [Field Tested] Harrington and Richardson PSA XM177E2 feature](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Harrington-and-Richardson-PSA-XM177E2-feature-100x70.jpg)