Just because a classic cartridge has served you reliably for many years doesn’t mean that you can’t upgrade to something more modern.

Standing over the zebra stallion—bedecked in his finest pajamas, in a pattern best described as art by God—I tapped the stock of my Mauser 98 to say thanks for a straight shot. I was using an obscure cartridge released in 1906, the .318 Westley Richards, and was more than happy to have revived an African classic.

Fast-forward 2 years, and I’d be standing in ankle-deep snow in northwest Colorado over a handsome mule deer buck, holding the then-unreleased 6.8 Western, the latest development in the .277-inch bore diameter. On that hunt, our group had taken both mule deer and elk at ranges between 25 yards and 475 yards, and I came away very impressed with the design.

I love cartridges, whether big or small, and I always do my best to give any new design a fair shake before deeming it unneeded. Reading the comments regarding any article on these new developments, traditionalists are the first to declare any deviation from their “ought-six” or “two-seventy” as heresy, and that any attempt at releasing a new cartridge is just a demonstration of corporate greed and should be shunned.

In the first two decades of the 21st century, there have been some great cartridges released, including the aforementioned 6.8 Western, PRC family of cartridges, .350 and .400 Legend, Federal’s .30 Super Carry, Nosler’s line of cartridges and, yes, the 6.5 Creedmoor.

Do they surpass the classics like the 30-06 Springfield, 7mm Remington Magnum, .300 Winchester Magnum and .243 Winchester? It truly depends on the application, your style and/or distance at which you hunt or shoot, and what you’re looking for in a cartridge. Let’s look at the concepts associated with the new cartridges and put them next to their older counterparts to see whether or not it might be a good idea to look into replacing your old favorite.

Shoot Longer, Shoot Flatter

The first design concept that needs mentioning is the sleek bullets that perform so well at longer ranges and in windy conditions. In order to increase the ballistic coefficient of a bullet (resulting in a flatter trajectory, better resistance to wind deflection and higher retained energy), the ogive of the bullet is elongated, using a flatter curve profile.

If you load these projectiles in a cartridge case of traditional length, quite often the resulting cartridge will be too long to fit in the magazine. The engineering answer was to shorten the case in order to provide more room for a longer bullet, whose longer ogive needs to be outside the case mouth.

This is a big part of the reason the 6.5 Creedmoor pushed the .260 Remington out of the limelight: If you stay within traditional hunting ranges, there’s nothing wrong with the .260 at all, but when distances get truly long, those higher B.C. bullets show their advantage. The Creedmoor has a definite edge. Add in a bit of marketing genius, and voila! … you’ve got the Creedmoor phenomenon.

The second concept, often tied in with the first, is the tightening of the twist rate within the barrel. I’ve shot a .22-250 Remington for almost a quarter-century, but I’ve always felt that the 1:12 is a handicap. The case has plenty of capacity to launch a bullet heavier than 55 or 60 grains (where the .22-250 tops out) and would be well-served by a heavy bullet. But, alas, the cartridge was designed when riflescopes were a rarity at best, so the 400-yard performance wasn’t really an issue.

Enter Federal’s .224 Valkyrie, with its 1:7 twist rate; slugs as heavy as 90 grains will be properly stabilized, and it’ll be able to utilize all the advantages of a higher B.C. bullet. The same can be said for the new 6.8 Western when compared to the .270 Winchester or .270 WSM. Where the latter pair use a 1:10 twist rate, which translates to the ability to stabilize bullets weighing 150 grains or, in some rare instances, 160-grain round-nose bullets, the 1:8 or 1:7.5 twist of the 6.8 Western allows the use of spitzer boat-tail bullets as heavy as 175 grains, in a case slightly shorter than that of the .270 WSM.

If you want the ability to use the heaviest slugs in 0.277-inch diameter, to my mind it makes perfect sense to buy a 6.8 Western—and I did exactly that. I can still use the 130-, 140- and 150-grain bullets common to the .270 Winchester, but if I want the option of reaching for a heavier bullet with a better sectional density value, I have it. The .27 Nosler delivers a similar performance level, topping out at 165 grains, in a faster package. Its 1:8.5 twist rate again allows the use of a 165-grain spitzer boat-tail bullet, offering both a velocity and bullet weight advantage over the .270 Winchester.

Do those points warrant a change on cartridge? Perhaps there’s something to this …

The Case Chase

Case design has also changed in the past 25 years, with the trends showing a general dislike for the Holland & Holland-style belted case. Instead, many designs have turned to the beltless and rimless .404 Jeffery as a platform, which uses the case’s shoulder for headspace rather than the belt of brass.

Belted cases are notorious for stretching, especially in the area just ahead of the belt, as the brass expands from each firing. This can not only have a negative effect on group size (as the case designed to headspace off the shoulder can offer better chamber concentricity), but it also reduces the life of the brass case. If you have no interest in reloading ammunition, the latter point likely won’t bother you, but if you appreciate an accurate rifle, the former point should.

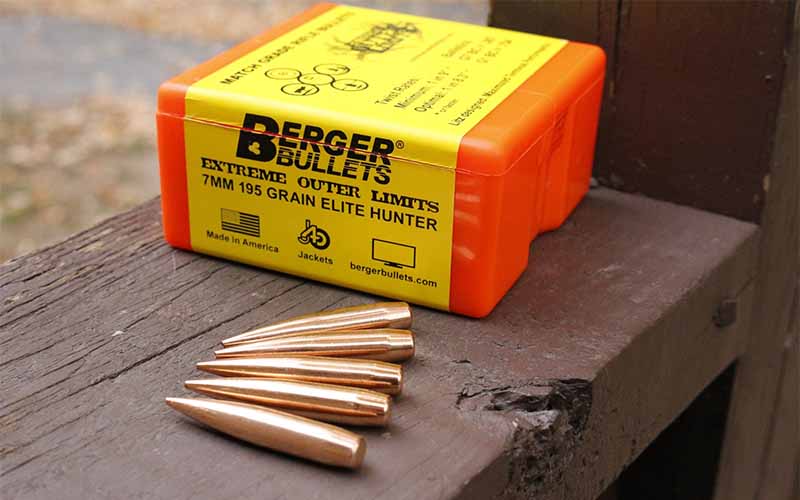

Looking at the ballistic differences between the popular 7mm Remington Magnum and Hornady’s new 7mm PRC, you might not see much at first. The newer cartridge gives a velocity advantage of 150 fps or so over Remington’s classic design. It’s also apparent that the 7mm PRC is built around bullets on the heavier end of the spectrum, as it’s offered in 175- and 180-grain configurations in the ELD-X and ELD Match bullets, and 160 grains in the monometal CX bullet.

Wait, can’t we get 175-grain bullets in the 7mm Remington Magnum? Yes, but not with the profile that can be used in the 7mm PRC.

If you’re a handloader, the PRC’s 1:8 twist will allow use of 180- to 195-grain bullets. Would this matter to the hunter who spends the vast majority of his or her time shooting at game animals inside of 300 yards? Probably not, but if a hunter wanted a new rifle fully capable of handling both hunting duties and weekend shooting competitions at long range, the 7mm PRC is the smarter choice.

I’ve used it in both circumstances and came away impressed by the performance. Will it kill the 7mm Remington Magnum? I don’t think so, as there a ton of rifles chambered for the 60-year-old cartridge, and they will still need to be fed.

New, But Necessary?

Remington’s new .360 Buckhammer surely doesn’t look like some newfangled wizardry; in fact, it could have blended in among the classic lever-gun designs of the late 19th century. It’s a straight-walled, rimmed affair, loaded with Remington Core-Lokt round-nose bullets.

So, what’s the big deal about this, and why would Remington go through the trouble and effort when they already make the hugely successful .35 Remington?

Well, it fits the criteria specified by several Midwest states and hunting areas, including a minimum bullet diameter of 0.357 inch, a straight-wall conformation (bottleneck cartridges are prohibited in many places) and a case length not exceeding 1.800 inches. The .35 Remington is bottlenecked (as is the .30-30 Winchester), and the .38-55 Winchester runs at relatively low pressure and lower velocity.

So, with a relatively blank slate, Remington offered a new cartridge that runs at even higher pressure than the .35 Remington, driving a 180-grain to 2,400 fps and a 200-grain bullet to 2,200 fps. This makes a great woods gun, as it hits harder than does the .35 Remington. And in the wonderfully accurate Henry rifle I had the opportunity to test, recoil was mild enough for a young shooter. Devotees of the .35 Remington might not be lining up to trade in their Marlins, but for a new hunter who likes lever-action rifles, this cartridge should certainly be in the lineup of prospective purchases.

The .30 Super Carry—Federal’s new handgun cartridge—is touted as a smaller cartridge that gives two additional cartridges in a double-stack magazine, or one more round in a single-stack mag designed to handle the 9mm Luger. With a 0.312-inch-diameter bullet weighing 100 or 115 grains, the .30 Super Carry gives a performance level mimicking the 9mm Luger with 125-grain slugs and surpasses that of the .380 Auto.

Is the shooting public ready for a deviation from the 9mm or .45 ACP? It doesn’t seem so, as I feel the .30 Super Carry is struggling to catch on, and the famous duo I just mentioned seem to check all the boxes for the vast majority of the concealed carry autoloader crowd.

Time Marches On

At one point in time, the .270 Winchester was a newfangled idea, and I’m certain the older hunters in 1925 just shook their heads, as a young Jack O’Connor championed the new speed demon. I’ve often written that there isn’t a hunt on Earth that I couldn’t handle with a cartridge released before 1930, which includes the .30-06 Springfield, .300 Holland & Holland Magnum, .257 Roberts (in wildcat form anyway), 7x57mm Mauser, .404 Jeffery and .375 Holland & Holland Magnum.

Both the 9mm Luger and .45 ACP were in service, and while the majority of the speedy varmint/predator cartridges were a ways off, I’ve had a bunch of fun hunting woodchucks and coyotes with a .22 Hornet. But I also feel there’s plenty of room for those new designs that truly offer something unique, like the 6.8 Western, .27 and .28 Nosler, and the 7mm PRC.

Our optics have certainly evolved and improved, and the metallurgy and uniformity of our rifled actions are better than they ever have been … and there should be a logical correlation in cartridge development.

But I’m not retiring my good-old .318 Westley Richards any time soon.

Editor's Note: This article originally appeared in the November 2023 issue of Gun Digest the Magazine.

Raise Your Ammo IQ:

- Beyond The 6.5 Creedmoor: The Other 6.5 Cartridges

- The Lonesome Story Of The Long-Lost 8mm

- Why The .300 H&H Magnum Still Endures

- .350 Legend Vs .450 Bushmaster: Does One Win Out For Hunting?

Next Step: Get your FREE Printable Target Pack

Enhance your shooting precision with our 62 MOA Targets, perfect for rifles and handguns. Crafted in collaboration with Storm Tactical for accuracy and versatility.

Subscribe to the Gun Digest email newsletter and get your downloadable target pack sent straight to your inbox. Stay updated with the latest firearms info in the industry.

![Best Concealed Carry Guns In 2025 [Field Tested] Wilson Combat EDC X9S 1](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Wilson-Combat-EDC-X9S-1-324x160.jpg)

![Best 9mm Carbine: Affordable PCCs [Tested] Ruger Carbine Shooting](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Ruger-Carbine-Shooting-100x70.jpg)

![Best AR-15: Top Options Available Today [Field Tested] Harrington and Richardson PSA XM177E2 feature](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Harrington-and-Richardson-PSA-XM177E2-feature-100x70.jpg)

The 360Remington and 400 Winchester Straight wall cartridges are indeed intriguing and represent the cartridges tha appeal to me for hunting whitetail, feral hog and close called in varmits. I like lever actions a lot, the bottle neck cartridges 30-30 and 32 Special ought to be allowed in straight wall states as exceptions since their ballistics mirror the 350, 360 and 400 new guys on the block, just my opinion. But the new ones do give me a reason to add to my rif;le ollection and thats not all bad.