There is nothing wrong with buying a used handgun. Assuming, of course, that there is nothing wrong with the used gun you are buying. But how to tell?

The process is simple: look, feel and listen. Look for things out of place; wear that is odd, or signs of abuse. Feel for the way it functions, compared to a new model or a known-good used one. (Obviously, experience helps, and already owning or having owned a similar handgun also helps.) Listen to the noise of the springs, the clicks, the slide cycling. They can all tell you something.

And ask. What does the owner/merchant know about it? Its history, previous owners, performance or reputation? Buying a competition gun can be good, and it can be bad. Was it the backup gun of a Grand Master that spent most of its time lounging in his range bag waiting its turn? (Can you say “tuned, low-mileage cream puff?”) Or was it the experimental subject of an aspiring gunsmith or competitive shooter? (Can you say “ridden hard and hung up wet?”) Be careful, ask, listen, and get the return policy in writing.

Etiquette of Buying Used

There are a few things you have to know about buying a used firearm. First of all, remember that until you hand over the money, it is someone else’s firearm you’re handling. It is entirely within the performance parameters of many handguns to be dry-fired from now until the end of time and suffer no damage. However, some people don’t believe it and will be very grumpy if you dry-fire their handgun. Ask before you dry-fire. If they refuse, then you have to either move on, or do your pre-purchase due diligence without dry-firing.

Ask before you disassemble, as, again, some people just don’t like having their handgun yanked apart. They may be cranky, and they may simply have had too many bad experiences with people who didn’t know what the frak they were doing.

Also, keep in mind that everything is negotiable. Point out details that ngiht lower the price. If the price can’t be lowered, ask about extra magazines, speedloaders, ammo, holsters, anything that improves the deal for you. Properly done, a purchase and negotiation is a social event, and not a dental visit.

Buying a Used 1911

When you’re considering a used 1911, start with a good visual inspection. Has the exterior been abused? Hammer marks or rough file marks on the outside should make you wonder how careful the previous owner was with the inside. If the original blued surface is now gray from years of use and carry, but the owner never dropped it and fired it seldom, you have a great opportunity. The looks are likely to bring the price down, but mechanically it can be just fine. If it is a pistol used in competition you might be able to find some answers by asking about its history with other competitors. Did the previous owner have a reputation of always shooting unreliable guns? Or were his pistols always reliable, just ugly?

After the visual inspection, start checking the operation. If you haven’t already done so, make sure the pistol is unloaded, and tell the clerk at the store that you want to perform some safety checks. Cock the pistol and dry fire it. Was the trigger pull very light? A very light trigger pull will have to be made heavier to be safe and durable. Or was it very heavy? Did it feel as if it was crunching through several steps before it finished its job? A very heavy or gritty trigger pull will have to be made smoother and lighter.

Execute a “pencil test.” Cock the pistol and drop a pencil down the bore, eraser end first. Point the pistol straight up, and dry fire it. The pencil should be launched completely out of the pistol. If it isn’t, something is keeping the firing pin from its assigned duties. Find out what before you buy.

You must perform a mechanical safety test. Cock the hammer again and push the thumb safety on. Holding the pistol in a firing grip, press the trigger a bit harder than you would to fire it. Seven or eight pounds of pressure is sufficient. Let go of the trigger, and push the thumb safety off. Now hold the pistol next to your ear, and slowly draw the hammer back. You should not hear anything. If you hear a little “tink” when you draw back the hammer, the thumb safety is not engaging fully.

If you heard the “tink,” here’s what happened. When you pulled the trigger with the safety on, the sear moved a tiny amount until it came to bear against the safety lug. It shouldn’t have moved at all. The hammer tension kept the sear from moving back into position when you pushed the safety off, leaving the sear partially-bearing on the hammer hooks. When you held the pistol close to your ear and drew back the hammer, that tension on the sear was removed. The sear spring pushed the sear back in place, causing the tink you heard. If the hammer stayed cocked, the sear only moved a tiny amount. The fix is easy. What if you never got to the “tink?” If the hammer fell when the safety was pushed off, before you even tried to listen, the thumb safety fit is very bad and you will have to buy and fit a new safety. In the worst case, the hammer falls even when the safety is on. These also need a need thumb safety. Considering the amount of work needed, and the possibility of other things being badly fit, you might just want to pass on this particular 1911. Unless, of course, you can get it for a very good price, and want to do the work yourself anyway.

Next test the grip safety. Cock the hammer, and, holding the frame so you do not depress the grip safety, pull the trigger. Release the trigger, and, now grasping the pistol so you do depress the grip safety, hold the pistol up to your ear again and draw the hammer slowly back. If you hear that tink again, the grip safety is barely engaging. Look at the grip safety. Because some competitive shooters don’t feel the need for one, they grind the tip of the grip safety off where it blocks the trigger. If this has been done to the 1911 you’re thinking of buying, you will have to have the tip welded back up, and fit it to the trigger. If the tip hasn’t already been ground off, or otherwise altered, you’re looking at an easy fix. It is probably just a simple mis-fit, which you can correct with careful peening.

The last test you need to perform is hammer/sear engagement, or hammer flick test. There’s a good way and a bad way to perform this test. In the caveman days we would lock the slide open empty. Then we would release the hold-open lever and let the slide crash home on an empty chamber. This is more like abuse than a test, especially since it doesn’t fairly test the hammer sear engagement. Continued “testing” this way can actually do harm to your hammer and sear. In the modern, improved “flick” test, you cock the hammer, grip the pistol so the grip safety is depressed, and hold down the thumb safety. With your other hand, flick the hammer back against the grip safety, and let the hammer go forward to sear engagement. This non-destructive test can be performed until the cows come home, or your fingers bleed, and will not harm the sear and hammer hooks. If, however, during this test the hammer falls — even once — the hammer/sear engagement will require work. You cannot depend on this pistol to stay cocked when firing. The pistol may simply require re-stoning the engagement surfaces, or it may require a new sear, or both new sear and hammer. Until you look at the engagement through a magnifier, there is no way to tell.

Aside from the grip safety check, which is unique to the 1911, these tests can be performed on any other pistol you might be considering for purchase, though double-action pistols require a modification of the thumb safety test. With the DA pistol unloaded and the hammer cocked, again place your pencil down the bore eraser end first. Point the cocked pistol up, push the hammer drop safety down to its safe position, and drop the hammer. The pencil had better not move at all. If it does, something is seriously wrong with the safety, and the future travel plans of that pistol include a trip to the factory. Push the safety off. With the muzzle pointing up, dry fire the pistol. Pick the pencil up off the floor, or investigate the firing pin’s malfunction.

With the safety checks out of the way, look for signs of abuse or experimentation. Take the slide off the frame and look at the frame rails. Have they been peened to tighten the fit? Even an ugly peening job can be fine, if the parts have been lapped for a smooth fit. If you’re looking at an after-market frame and slide combination like the Caspian, put the slide back on the frame without the barrel and recoil spring assembly. Such combinations left the manufacturer as a tight fit and were lapped to slide smoothly. If the pistol is now very loose, it has had many, many rounds through it. The barrel may need to be replaced. The price had better reflect this.

With the slide off, look at the feed ramp. Has it been polished? Polishing is fine. Has it been re-ground, altered or subjected to an incorrect “feed” job? These alterations can be a problem. If the ramp has been incorrectly altered, the pistol will feed poorly, and if the top of the feed ramp has been rounded off, the pistol will not feed at all. Take the barrel and place it on the frame in its unlocked seat, ahead of the feed ramp. Push it all the way back into the cutout, and check the relationship of the barrel to the feed ramp. There should be a small gap between the bottom of the barrel and the top of the feed ramp. A gap of 1/32nd of an inch is about right. A smoothly rounded and blended fit is the indication of a bad feed job. Such a pistol will feed only with round-nose, full-metal-jacket ammunition, if at all. Anything else will hang up. The fix, which involves welding the frame and re-cutting the surfaces is expensive. Unless you can get the pistol for a song, pass on it.

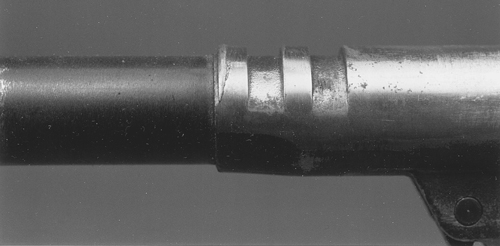

Look closely at the barrel. The feed ramp of the barrel should not be altered, only polished. Ramping the barrel deeper into the chamber was a prehistoric method of ensuring reliable feeding, and is not an acceptable practice anymore. An over-ramped barrel has to be replaced. Look at the locking lugs. Are they clean and sharp? They should be. If they are rounded, or show a set-back shoulder or burred edge, the barrel was improperly fit to the slide. If only the barrel is damaged, a new barrel properly fitted will solve the problem. If the slide locking lugs are also damaged, then you have to replace the top end. Putting a new barrel into a slide that has rounded, set-back or otherwise damaged locking lugs will only damage the new barrel, wasting your money.

Look at the barrel bushing. Some bushings are cast of soft metal, and the locking lug will deform against the harder slide. If it hasn’t already, then in short order the wear will harm accuracy. A new bushing solves this problem at low cost.

Are there cracks in the frame? Many shooters worry about visible cracks, though some do not matter. A crack in the dust cover over the recoil spring is not a concern unless it is extensive, or you are planning to mount a scope right there. This common crack results from contact between the top edge of the dust cover and the slide. Many shooters feel that since the stress between the dust cover and the slide has been relieved by the crack, any problem has been solved. If, however, you still want to eliminate the crack, you must first file down the top of the dust cover to keep it from contacting the slide. Then have the crack welded. Another common crack, through the left rail at the slide stop cutout, is so normal and harmless that Colt actually incorporated it into the design when they began machining the cutout hole completely through the rail.

Buying a Used Revolver

Buying a revolver, single- or double-action, involves pretty much the same process as buying a used pistol. First, assess the exterior to see if the revolver shows signs of hard use or abuse.

Look at the finish. Is it heavily worn or scratched? A used blued revolver will show white steel at the corners of the frame and cylinder. This wear is caused by holstering and drawing, and is normal. If the scratches look as if a sidewalk instead of a holster caused them, pass on this revolver. Or if you see scratches down to copper on a nickel revolver, pass again. A used revolver with a shiny new finish may have been re-blued or re-nickeled and needs close examination to determine its condition. Look at the screw holes. Are they oval? Not good. Incorrectly used, the fabric of a polishing wheel will reach down into the screw hole and dish it out. The proper, factory method of re-polishing requires fitting sacrificial screws to the frame. After the frame is polished, these screws are thrown away and new ones are fitted. Look also at the letters and markings. Do they look as if they are blurry? Blurry letters and markings in an otherwise shiny and good finish with good screw holes tell you that the polisher was careful. While he didn’t dish the screw holes, he couldn’t avoid “pulling” the markings. Blurry markings do not harm function, but should lower the price.

To determine if the revolver was ever dropped, check the muzzle, sights and hammer spur for dents and dings. In extreme cases, the sights will have been bent or broken completely off. A revolver with a dinged muzzle but a new front sight was dropped hard enough to break the sight, which was then replaced. Unless you can check barrel straightness and cylinder alignment before you buy, pass.

Look at the cylinder for these same dents and dings. If you see marks, gently open and close the cylinder. A dropped double-action revolver that lands on its cylinder can end up with a sprung crane. If you have to press firmly with a thumb on the cylinder to get the centerpin to click into its seat in the frame, the crane needs alignment. Straightening it is an easy operation.

To check function on the single-action revolver, first make sure it is unloaded. While holding the revolver with your firing hand, grasp the cylinder with your other hand and try to move it back and forth. A very small amount of movement is okay. If the cylinder moves more than the smallest fraction of an inch, however, you may have to adjust endshake after you buy it. Not a big deal. If the cylinder moves so much you can actually hear it clacking back and forth, buy this revolver only if it is cheaper than dirt, or you like a good re-building challenge.

Gently cock the revolver. In the old-style single-actions, (direct copies of the Colt SAA), you should hear four distinct clicks. Odd, tinny sounding clicks could mean weak springs or modified parts. Muffled clicks usually mean the action is over-oiled or greased. Gently cock the revolver through all six chambers. As you do this you must be sure to move the hammer slowly and deliberately to eliminate any momentum in the cylinder. As an additional test, lightly press a thumb or fingertip against the cylinder, to add drag. Did the revolver fully carry-up, that is, did the cylinder come all the way up and lock? If it did not, the revolver may have a short hand or a worn ratchet. Though these problems are easy to fix, try to bargain the price down.

Do the pencil/firing pin test again, to make sure the firing pin is striking hard enough.

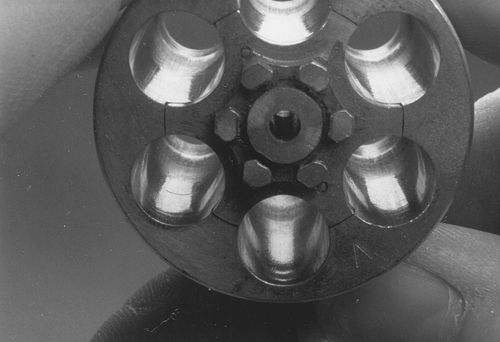

Look at the locking slots on each chamber. If they are burred or chewed up the revolver has probably seen too many sessions of fast-cocking shooting, or god forbid, fanning. Pass on the revolver.

Pull the center pin out, remove the cylinder, and look at the locking bolt. Is it beaten up? Are its edges peened? Heavy use, or just a bit of fanning and fast-draw practice will wear the locking bolt. While the bolt is cheap to replace, the cylinder is not. Heavily worn locking slots on the cylinder mean an expensive repair. Pass on the revolver.

Finally, look at the back of the barrel. If the forcing cone is caked in powder residue and lead, ask if it can be cleaned up. You need to see it. Check that the edges of the forcing cone are sharp. A worn or rounded edge means the revolver has seen lots of shooting. Is the rifling clean and distinct? Heavy use erodes the rifling as well as the edges of the forcing cone. Setting the barrel back and re-cutting the cone can rectify a barrel with heavy wear in the forcing cone.

Cracks in the forcing cone cannot be fixed. Uncommon outside of magnum revolvers, these cracks result from the high pressure of the magnum ammunition stressing the edges of the forcing cone. Unlike wear, you cannot easily set the barrel back enough to fix a crack. With a cracked forcing cone it’s much simpler just to replace the barrel.

With double-action revolvers you do all the same external checks that you did with the single-action revolvers. A significant percentage of the double-action revolvers available on the used market are ex-police revolvers. When police departments switched to automatics, they traded in or sold their revolvers. Pay attention to the details and you can get a good deal on a used double-action .38 or .357.

Many ex-police revolvers have the bluing rubbed off where they rode in a holster, but otherwise have little wear. Since many police departments qualify only annually, your revolver may have had only a couple of hundred rounds a year put through it! The grips, if original, will probably be very ugly. While rest of the revolver was protected by the holster the grips were outside, getting banged by car doors, signposts, and who knows what. Grips are cheap and easy to replace.

To begin your mechanical checks, first release the cylinder latch and swing it open. Is the revolver loaded? No? Good. Swing the cylinder in and out several times. Make sure it swings smoothly, and closes easily. Smith & Wessons binding while swinging usually means the sideplate screws have been switched. In other brands, it means the crane is dirty. If you have to press the cylinder to make it click when closing, the crane is out of alignment.

There are two checks for carry-up, one for single-action cocking and one for double. Single is simple. Slowly cock the action while watching the cylinder, just as you would for a single-action revolver. I do my double-action check very, very slowly, with my left thumb against the hammer, so when the trigger releases the hammer, the momentum of my trigger finger doesn’t throw the cylinder into lockup. You can also use a fingertip to drag against the cylinder. Although failure to carry-up can be fixed, you should bargain for a lower price because of it.

Open the cylinder and look at the forcing cone, on the back of the barrel. Give it the same thorough exam described for a single-action revolver.

Now look into the cylinder. At the front of the chamber is the shoulder. A magnum revolver that had a lot of .38 Specials put through it would have developed a crusty ring just in back of this shoulder. You may also see such a ring in single-action revolvers, where many competitors use shorter cases for lighter loads. It may be that the .357 Magnum you are looking at has been fired extensively with cases not much longer than a 9mm Parabellum, and the forward half of each chamber is sheened with lead. There can be corrosion under the crusty buildup. Ask to have any visible grunge scrubbed out, and check the area for the pits that indicate too much time between cleanings. Pits can make extraction harder when you fire magnum ammunition, and continue to rust if you use Specials. If the revolver has pits, don’t buy it.

Check the back of the cylinder, at the openings to each chamber. If the revolver was used for competition, the chamber openings may have been chamfered to allow faster reloading during matches. Poorly done, however, chamfering makes ejection uncertain. Look at the work closely. Only the cylinder itself should be beveled. If the extractor star is also beveled, ejection may suffer. To check, you need to fire the revolver and eject the empties for at least 100 rounds. Since the cure for a bad chamfering job is fitting a new extractor, an expensive factory job, if you can’t shoot the revolver beforehand or get a warranty pass on it.

During your test-fire you may find that the sights are off slightly. On a revolver with adjustable sights, just crank them over. (Indeed, this is a good time to find out if the adjustable sights actually adjust.) In a fixed-sight revolver a small amount of “off” is OK. After all, you’ll want to be able to adjust your new revolver to you and your ammo. However, if the sights are off more than a few inches at 25 feet, or the groups with standard ammo for the caliber, are hitting high, you may have problems. A few inches is about all you can correct by turning the barrel. A high bullet strike means a low front sight, and it is difficult to add height to a fixed sight. Take a quick look and see if the sight has been filed or machined. If it hasn’t, the frame may be bent, and only the factory can correct that. And not for free. You must make a choice: is this a project gun, for experimentation in fitting a new front sight, or is it a returned gun, for your money back? Only you can decide.

Next Step: Get your FREE Printable Target Pack

Enhance your shooting precision with our 62 MOA Targets, perfect for rifles and handguns. Crafted in collaboration with Storm Tactical for accuracy and versatility.

Subscribe to the Gun Digest email newsletter and get your downloadable target pack sent straight to your inbox. Stay updated with the latest firearms info in the industry.

![Best Concealed Carry Guns In 2025 [Field Tested] Wilson Combat EDC X9S 1](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Wilson-Combat-EDC-X9S-1-324x160.jpg)

![Best 9mm Carbine: Affordable PCCs [Tested] Ruger Carbine Shooting](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Ruger-Carbine-Shooting-100x70.jpg)

![Best AR-15: Top Options Available Today [Field Tested] Harrington and Richardson PSA XM177E2 feature](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Harrington-and-Richardson-PSA-XM177E2-feature-100x70.jpg)