A discussion on the pleasures and pitfalls of small-bore centerfire cartridges.

When a rifleman decides to make the move to a small-bore rifle—whether for hunting, target shooting or for defensive measures—their choice of cartridge usually ends being highly debated. I’ve seen guys who were friends for decades get extremely hot under the collar when arguing the .22-250 Remington versus the .220 Swift, to the point where I thought it might come to blows.

Bring up the .204 Ruger and you might find a shooter who feels that all other bore diameters are an absolute waste of time, and the shooting world was just waiting for a .20-caliber cartridge. And then there’s the huge crowd of folks who feel that small-bore cartridges begin and end with the 5.56mm/.223 Remington, and that’s that.

For the hunter/shooter looking for a small-bore cartridge to best fit his or her needs, there are some considerations to keep in mind with any of the small-bore choices, and the more you know, the easier the choice will be. Let’s look at some of the more common choices between .17 and .22 caliber, and what each has to offer.

The Teenagers

This .17 caliber is the smallest bore diameter of the commercially loaded cartridges and offers some serious heat. This bore diameter can be traced back to the Flobert rifles—using no powder, only a primer as propellant—and was championed by P.O. Ackley. Remington was the first to legitimize the 0.172-inch-caliber cartridges, with the 1971 release of the .17 Remington.

Based on a slightly modified .223 Remington case, the .17 Remington will propel 20- and 25-grain bullets to a muzzle velocity of 4,250 fps and 4,040 fps, respectively. This velocity level will test the mettle of any bullet, let alone frangible varmint bullets of 20 to 25 grains, and the .17 Remington can be nearly explosive upon impact. The hydraulic shock generated will certainly create “red mist” when used on woodchucks and prairie dogs, and if placed correctly, it will hold even the bigger Eastern coyotes.

The .17 Remington can be hell on barrels, especially if you overheat them, and fouling can be a real issue if you don’t stay on top of it. Accuracy will degrade, and cleaning any of the .17 bores can be a challenge, as it requires a cleaning rod of special diameter, as well as tiny little patches.

Remington also had the distinction of producing the second commercial .17-caliber cartridge, when interest in the .17 Mach IV wildcat warranted the development of the .17 Remington Fireball in 2007. Necking down the .221 Fireball resulted in a cartridge that offers a muzzle velocity rather close to the .17 Remington—driving a 20-grain bullet to just over 4,000 fps and a 25-grain bullet at more than 3,700 fps—in a smaller case. I find the .17 Remington Fireball to be a bit more barrel friendly than the larger .17 Remington, but despite a bit of fanfare upon release, factory ammunition is becoming increasing rare … if you can find it at all.

The youngest of the bunch—Hornady’s .17 Hornet—is based on a P.O. Ackley wildcat, which necked down the highly popular .22 Hornet to hold .172-caliber bullets. While the Ackley variant used a 30-degree shoulder to help increase case capacity, the Hornady version uses a 25-degree shoulder, albeit with less body taper.

Despite the rimmed case, the .17 Hornet feeds well in bolt-action rifles, including the Ruger rotary magazine. With a 20-grain bullet leaving the muzzle at 3,650 fps, the .17 Hornet is the best balanced of the .17-caliber cartridges. Despite the fact that it gives up 600 fps to the .17 Remington, the lack of ear-splitting report, while still delivering a respectable trajectory, makes a huge difference.

Looking at downrange trajectory, you’ll see an arc very similar to that of the .30-06 Springfield. That 20-grain V-Max—when zeroed at 200 yards—will strike 6½ inches low at 300 yards and 20½ inches low at 400 yards, though the wind deflection of the diminutive cartridge is twice that of the ought-six. But once you become accustomed to the .17 Hornet in the wind, you’ve got a rather potent little package. A 20-grain bullet will work on bigger coyotes up close, but outside of 150 yards or so it might struggle to hold them. Nonetheless, I like having a .17 Hornet in my lineup.

Anyone For A 20?

In 2004, Hornady worked with Ruger to create what would become the second-fastest small-bore: the .204 Ruger. Based on the .222 Remington Magnum and using a bullet of nominal diameter, the factory loads would use a 32-grain bullet to break the 4,200-fps barrier. A 30-degree shoulder handles the headspacing duty.

Although the 32-grain bullet generates some impressive velocity figures, there are bullets available weighing up to 55 grains, including Hornady’s 40-grain V-Max at 3,900 fps, making a good load for longer range hunting and shooting. The heavier bullet weights require a 1:10 twist rate for proper stabilization, rather than the standard 1:12 supplied in most factory barrels. I like the .204 Ruger as a happy medium between the .17s, which use considerably lighter bullets, and the .22-caliber centerfires, which have the bullet weight but can sometimes be too much of a good thing when it comes to small-bores.

Hornady is a prime source of ammunition, but there have been factory loads from Federal, Winchester, Remington, Nosler, Sierra and more. Many of the loads seem to be produced as seasonal runs. There are plenty of good component projectiles out there, and the .204 Ruger isn’t a particularly finicky cartridge to load for. If you enjoy cartridges a bit out of the norm, the .204 Ruger is a neat choice, which will be effective in the field or at the target range.

Catch 22

When I think of centerfire small-bore cartridges, my mind goes immediately to .22 caliber; perhaps it’s because that was as small as things went when I was a young. From the classic .22 Hornet of the 1930s, to the undeniable popularity of the .223 and Triple Deuce, and the faster .22-250 Remington and .220 Swift, it seemed that these cartridges were resigned to killing woodchucks and foxes. There were, however, some adventurous deer hunters who would employ a .222 Remington or .22-250 Remington to fill the freezer, with mixed results.

There are plenty to choose from, with some fading into obscurity and some older ones still hanging on. Yes, I think the .219 Zipper, .224 Weatherby, .225 Winchester and .22 Savage HiPower are cool, but they aren’t popular at all any longer. So, I’ll compare and contrast the more popular—and attainable—.22-caliber centerfires.

The .22 Hornet has its roots back in the late 19th century, but the cartridge we all know and love came onto the scene in 1930, having been molded by the likes of Grosvenor Wotkyns and Townsend Whelen at the Springfield Armory, bearing a serious resemblance to the blackpowder .22 WCF. Though it’s rimmed, the Hornet has been adapted to a wide number of rifle actions, from bolt-action to falling-block single-shots, to double rifles and drillings. With a slight shoulder measuring just over 5½ degrees, the Hornet feeds nicely from a box magazine and will push a 45-grain bullet to nearly 2,700 fps.

While this might not be setting any velocity records, it’s good enough for varmints and furbearing predators up to and including coyotes. It has very little recoil, and the report won’t flatten eardrums. Ammunition is still available from a number of manufacturers—though it seems to be produced in limited runs—and offers projectiles weighing between 30 and 46 grains. If you want a low-recoiling choice for taking varmints and furbearers inside of 200 to 250 yards, the .22 Hornet surely deserves consideration.

The .222 Remington was a gamechanger when it burst onto the scene in 1950 in the Remington Model 722 bolt rifle. Developed by Mike Walker, the Triple Deuce was the first commercially loaded rimless .22-caliber centerfire cartridge, and it smashed all sorts of accuracy records. Compared to the larger, speedier cases, it has very tolerable recoil, and a 50-grain bullet traveling at right around 3,200 to 3,350 fps doesn’t exactly disappoint at moderate ranges. The 23-degree shoulder handles the headspacing duties, and the neck measures 0.313 inch, giving plenty of neck tension.

The .222 Remington had its heyday here in the United States, but it long ago lost the popularity contest to the .223 Remington and .22-250 Remington. However, it remains popular in those European countries where military ammunition is prohibited for hunting. Inside of 400 yards, hits were rather consistent, but past that distance it became increasingly difficult, especially in comparison to the .223 Remington. But for the eastern woodchuck hunter who wants a target cartridge for shorter ranges, the Triple Deuce might be a great solution. Should you find a rifle so chambered, don’t count it out.

The Standard

There really isn’t too much I can add to the .223 Remington that hasn’t been said a million times, but it does possess some qualities that set it apart from other .22-caliber cartridges. It’s slightly longer than the .222 Remington, with the same 23-degree shoulder and 0.378-inch case diameter, yet has a shorter neck. This yields a greater case capacity and a correlatively faster velocity.

And, to change the game even further, many modern rifles chambered in .223 Remington offer a tight twist rate—sometimes as tight as 1:7—which allows the use of heavy-for-caliber bullets that best retain energy and resist wind deflection. A 77-grain bullet at 2,700 fps will perform much better at longer ranges than any lighter bullet when the targets are out past 500 or 600 yards, and the winds begin to wreak havoc with your bullet. If you want a flexible package, which is affordable to shoot, with a multitude of ammunition choices, look no further than the .223 Remington; it can be handloaded easily, it’s easy on the shoulder, and though it may lack the sparkle of newer cartridges, it just plain works.

The Newbies

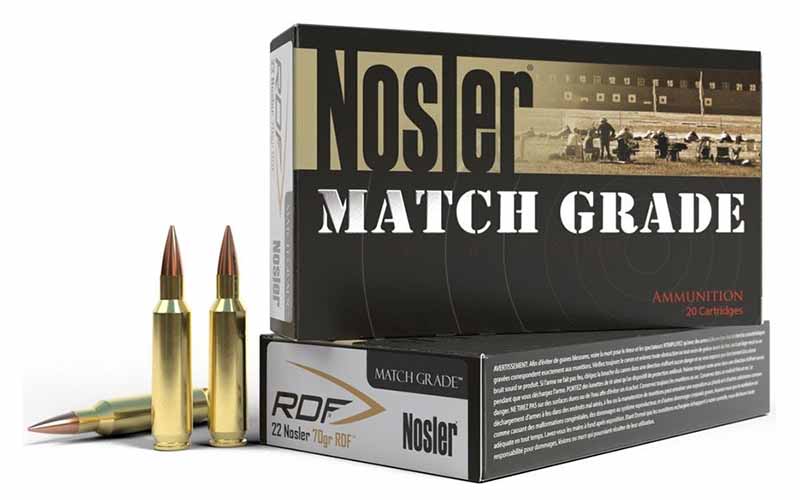

The .22 Nosler reared its head in early 2017, and was designed to mate up perfectly with the AR platform, giving superior ballistics to the .223 Remington/5.56 NATO, and approaching those of the .22-250 Remington. With a 1:8 twist rate, the .22 Nosler offers heavier bullets in the loaded ammunition, including 70-, 85- and 90-grain choices. It has a rebated rim and a 30-degree shoulder for headspacing, but it makes the most sense in an AR rifle.

The main issue with the cartridge is that Nosler is the only source of ammunition, and the cartridge seems to be fading fast. Nonetheless, the formula makes sense and if speed is your thing, the .22 Nosler has no flies on it.

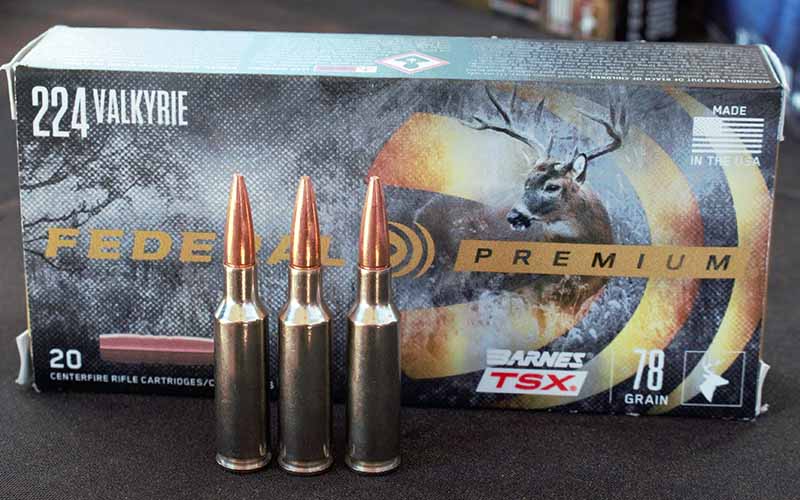

Federal’s .224 Valkyrie is a long-range cartridge, for sure, with a twist rate of 1:7 to handle the heaviest .22-caliber bullets. Based on the 6.8 SPC, the .224 Valkyrie was released at 2018’s SHOT Show. The rimless case uses a 30-degree shoulder like the .22 Nosler but is more adaptable to a bolt-action rifle. Factory ammunition will offer bullet weights between 60 and 90 grains and is available not only from Federal, but from Hornady and Sierra, in both hunting and match-grade target loads.

It’s probably the best choice for those who want a .22-caliber centerfire that can readily handle deer and similar-sized game, as well as the varmints and furbearers, yet readily handle a 1,000-yard target range. Of the new releases, I like the .224 Valkyrie a whole lot.

The Speedster

Remington’s .22-250 spent more than a quarter-century as a wildcat cartridge, being nothing more and nothing less than the .250-3000 Savage necked down to hold .224-diameter bullets. One of the most popular variants was developed by Grosvenor Wotkyns, J.E. Gebby and J.B. Smith, rivaling the .220 Swift’s velocity levels. Ironically, the .22-250 was one of the only cartridges to have a commercial rifle chambered for it before any commercial ammunition was available. Browning made a rifle chambered in 1963, while the Remington ammunition wouldn’t be offered until 1965. Our own John T. Amber commented on the situation in the 1964 Gun Digest Annual, reporting, “As far as I know, this is the first time a first-line arms-maker has offered a rifle chambered for a cartridge that it—or some other production ammunition maker—cannot supply.”

The .22-250 is still a highly popular cartridge among the small-bore crowd, as it offers impressive velocities and can deliver hair-splitting accuracy. But, the cartridge has both pleasures and pitfalls: The case capacity is almost wasted because the twist rate prevents bullets heavier than 55 grains, or maybe 60 grains if the conformation is correct. A 55-grain slug can be driven to 3,800 fps, and while that’s impressive, I contemplate re-barreling my rifle from the standard 1:12 twist down to a 1:8 or 1:7 twist to accommodate the 85- and 90-grain bullets, which would take full advantage of the case capacity.

Factory loads are available from nearly any company that loads ammunition, and the handloaders have long embraced the case. In fact, Hodgdon’s H380 spherical powder is named for the 38.0-grain load of surplus military powder that Bruce Hodgdon used under a 55-grain bullet in the (then wildcat) .22-250 case.

With a 0.473-inch rim, and a neck measuring 0.248-inch long, the case has all sorts of capacity, but unlike the modern cartridges, is handicapped by the twist rate common to yesteryear. Or is it?

If you want your small-bore rifle to simply handle the smaller species and some target duties at moderate ranges, the .22-250 Remington has no drawbacks whatsoever. But if you want to stretch the capabilities, extending the .22-250 into the regions of a deer rifle, the standard design with the slower twist rate will not stabilize the heavier projectiles, and even the .223 Remington can be a better choice.

The Swift

The .220 Swift has been a topic of debate since its release in 1935. Again, Grosvenor Wotkyns had a hand in the development (seeing a trend here?) of the world’s fastest cartridge, and in the midst of the Great Depression it broke all sorts of barriers. It’s fast—well over 4,000 fps—and that came at a price, namely eroded throats and worn barrels.

Much like the .22-250 Remington, using the .220 Swift in a high-volume shooting situation isn’t the best for the throat or rifling, as things heat up pretty quickly. And again, like the .22-250, the majority of rifles chambered for the .220 Swift use a barrel with a relatively slow twist rate—either 1:14 or sometimes 1:12. This twist rate was common for .22-caliber barrels of the era and will preclude the use of bullets much heavier than 55 grains, as they won’t be properly stabilized, and you’ll see those nasty keyhole marks on your targets.

And The Winner Is?

So, which cartridge do you choose?

Like so many things in life, the answer is highly subjective and truly depends on your hunting/target needs. If you’re looking at things from a purely practical viewpoint, the .223 Remington offers the greatest amount of flexibility and literal bang for the buck. It’ll check all the boxes and do so affordably.

But practicality isn’t always applicable, and some folks enjoy shooting a cartridge that’s either a nostalgic classic—in the case of the .22-250 Remington or .220 Swift—or one of the technological wonders designed to be cutting edge, like the .224 Valkyrie or the .204 Ruger.

I’ve settled on two: the .17 Hornet and the .22-250 Remington. The former chose me, after spending a week killing prairie dogs with a plethora of different cartridges, and the latter I chose as a much younger man, who believed he needed the velocity. I’ve had many opportunities to revise both choices—yet I have not—as I know both the rifles and cartridges very well, and they cover all the bases I need a small-bore cartridge to cover.

Be honest with yourself regarding hunting distances and game pursued, or if you’re looking for a target cartridge, assess your goals and needs and pick a cartridge that’s both available and accessible. You’ll probably make a friend for life.

Editor's Note: This article originally appeared in the January 2024 issue of Gun Digest the Magazine.

Raise Your Ammo IQ:

- Beyond The 6.5 Creedmoor: The Other 6.5 Cartridges

- The Lonesome Story Of The Long-Lost 8mm

- Why The .300 H&H Magnum Still Endures

- .350 Legend Vs .450 Bushmaster: Does One Win Out For Hunting?

Next Step: Get your FREE Printable Target Pack

Enhance your shooting precision with our 62 MOA Targets, perfect for rifles and handguns. Crafted in collaboration with Storm Tactical for accuracy and versatility.

Subscribe to the Gun Digest email newsletter and get your downloadable target pack sent straight to your inbox. Stay updated with the latest firearms info in the industry.

![Best Concealed Carry Guns In 2025 [Field Tested] Wilson Combat EDC X9S 1](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Wilson-Combat-EDC-X9S-1-324x160.jpg)

![Best 9mm Carbine: Affordable PCCs [Tested] Ruger Carbine Shooting](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Ruger-Carbine-Shooting-100x70.jpg)

![Best AR-15: Top Options Available Today [Field Tested] Harrington and Richardson PSA XM177E2 feature](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Harrington-and-Richardson-PSA-XM177E2-feature-100x70.jpg)

As it goes, the 5.7×28 seems to never be part of the conversation and it deserves to be. The 57 is a ninety’s innovation by FN to replace the 9mm. The 57 is a fast , accurate, small, hard hitting soft shooting round made for less than 100 yards that is a perfect varmit round. I don’t understand why it’s ignored.

If you love your 17 Hornet, try the 19 Calhoon or 19 Badger

6 x 45mm (223 Remington necked up to 6mm) is hugely popular in South Africa especially by game farmers having to cull herds.