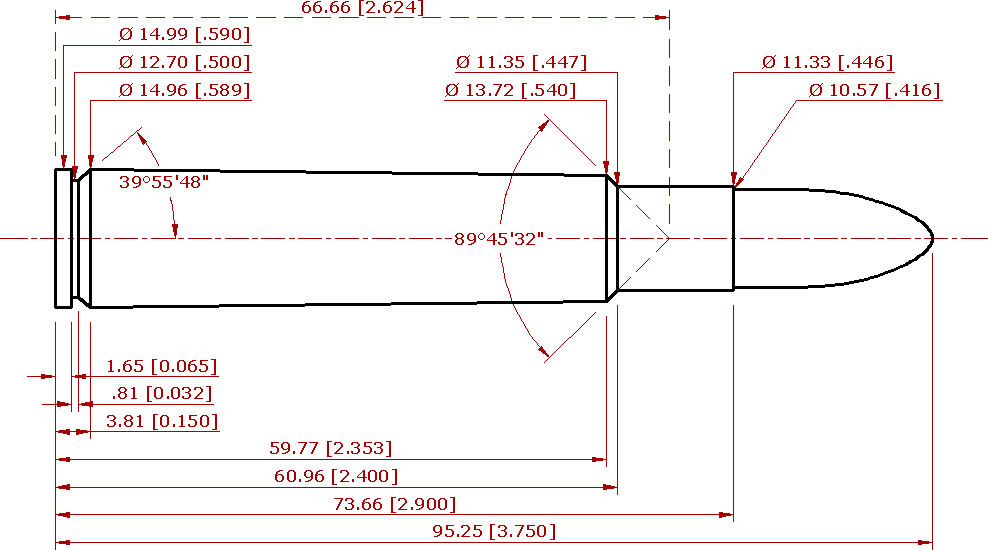

The 6mm Remington cartridge dimensions, and the .244 Remington cartridge dimensions, are exactly the same. However, rifles chambered for the cartridge and factory loaded ammo for each usually differ a bit.

The reason for this anomaly, at least to me it is an anomaly, makes an interesting story. Remington has done it at least once more that I'm aware of, and perhaps more than that. More later on this issue.

In 1955, both Remington and Winchester introduced similar 6mm cartridges to the marketplace. Winchester's version was the .243 Winchester, and Remington dubbed their version the .244 Remington. The two cartridges were quite similar. Winchester made theirs by necking down .308 cases to 6mm and chambered its Model 70 and Model 88 lever action rifles for the new cartridge.

Many other manufacturers began chambering for the cartridge shortly thereafter. Winchester developed the cartridge as a combination varmint round using lighter weight bullets, and a light deer/antelope rifle using 100 grain bullets. Winchester fitted their rifles with a 1:10 twist barrel, which would stabilize all bullet weights suitable for both purposes.

Remington, on the other hand, saw their .244 cartridge as a varmint/predator cartridge and discounted any demand for it as a deer/antelope rifle. Therefore they fitted their rifles with a 1:12 twist, perfect for the 80-90 grain bullet weights, but wouldn't always stabilize the 100 grain and heavier bullet weights that hunters wanted to use on deer and antelope. As the old adage goes, the rest is history. Winchester's .243 became a very popular cartridge and Remington's .244 almost withered on the vine, even though technically it offered slight advantages over the .243.

Remington finally saw the error of their ways and in 1963, they changed the twist from 1:12 to 1:9, which would stabilize all available 6mm bullet weights available on the market. Since they realized that the damage had already been done to the .244 Remington, they changed its name at that time to the 6mm Remington. With the head start of the .243, the 6mm Remington has never caught up with the popularity of Winchesters offering, but it has, as best I can tell, become a reasonably successful cartridge offering for Remington, as well it should.

As mentioned earlier, it offers a slight ballistic advantage over its Winchester rival. Remington chose the 7×57 Mauser cartridge as the parent case for its 6mm offering, which gives it a slightly greater powder capacity than the .308 based .243. It also provides a slightly longer cartridge neck, which most handloaders prefer, including this one. Practically speaking, however, if that is permitted these days, they are ballistic twins. What one will do, so will the other and equally well.

And now, as the late Paul Harvey used to say, “the rest of the story!”

I mentioned earlier that Remington had changed cartridge names at least one other time that I am aware of. In that case, it was with the .280 Remington, the 7mm Remington Express, and back to the .280 Remington again. You'd think they would learn. The cartridge never changed, only the name, and for different reasons than the .244 vs. 6mm Remington debacle.

Winchester introduced the .270 Winchester in 1925. I've written about it here in this series as it is one of my designated “greatest cartridges.” Remington did not have a really similar cartridge offering so in 1957, they introduced the .280 Remington (which had been around in a slightly different guise as the 7×64 Brenneke for even a bit longer than the .270 as it was introduced in 1917.)

The .280 is basically the .30-06 case necked down to .284” with a couple slight modifications to prevent a .270 cartridge being chambered in a .280 chamber. The resulting cartridge is a very good one, in some ways a bit better than the .270, but it has never caught up with the .270's head start.

In an effort to boost sales, from 1979 to 1980, Remington cataloged the round as the 7mm Express Remington, which did nothing for sales and confused the hell out of a lot of folks! Again, they saw the error of their ways and went back to calling it the .280 Remington.

![Best Concealed Carry Guns In 2025 [Field Tested] Wilson Combat EDC X9S 1](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Wilson-Combat-EDC-X9S-1-324x160.jpg)

![Best 9mm Carbine: Affordable PCCs [Tested] Ruger Carbine Shooting](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Ruger-Carbine-Shooting-100x70.jpg)

![Best AR-15: Top Options Available Today [Field Tested] Harrington and Richardson PSA XM177E2 feature](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Harrington-and-Richardson-PSA-XM177E2-feature-100x70.jpg)