The M1 Garand's rich history continues to grow as this rifle remains a popular option among collectors and competitors.

The rifle taking shape on John Cantius Garand’s drawing board in the 1920’s, even to 1932, was a very radical departure from its predecessors, not merely because it was a semi-automatic.

Garand conceived and designed the rifle and the tools and machines that would produce it. For the first time, it was a truly unique U.S. design. The Springfield single shots had been mundane but reliable, nothing that startled anyone. The Krag-Jorgenson rifles, from 1892, were beautifully made, the work of Ole Herman Johannes Krag and Erik Jorgenson, but genuinely obsolete from their inception. The ’03 Springfield was a fine rifle, based purely on the Model 1898 Mauser, license arrangements resulting in the payment of hundreds of thousands of dollars to the originating firm in Oberndorf.

Any new military firearm stirs up the “old guard.” This wild new thing, controversial from the very first announcements, stirred up imaginations and resentments far and wide.

Using the “gas trap” system, involving a false muzzle, handling a huge volume of hot, still expanding gases, was radical enough with the then-new .276 Pedersen Center Fire cartridge. There was considerable use of stainless steel in the gas cylinder and the piston of the operating rod. Using new, faster powders, it seemed the new cartridge would obviate the issues of sludge, residue and secondary ignition that plagued other such contraptions in the U.S., Great Britain, Belgium, Germany and Russia.

For the first time in a modern infantry rifle, simple snap-apart field strip for ordinary cleaning was built into the design, and even detailed stripping was possible with only a bullet as a tool, albeit often when finished such a projectile often wound up distorted beyond normal parameters.

About 1932, Army Chief of Staff Douglas MacArthur determined that the new cartridge was uneconomical and ordered that the new rifle had to be redesigned to utilize the millions of rounds of .30/06 ammunition still extant, produced for World War I. This was the second major change, as the original design had been primer actuated. Garand was resourceful, and by 1936, the rifle was adopted and in production.

Talk concerning ammunition wastage and safety issues began immediately in the popular press. Digging out old newspaper articles can be fascinating; some refer to the firearms blowing up, others spontaneously disassembling. Rumors about excessive cost and other “boondoggle” whispers got rolling. Many firearms writers of the times jumped on this bandwagon. During the Great Depression, it seemed extravagant. And firearms companies who had (or more often, simply claimed they had!) competing designs were not at all averse to planting tales about weapons allegedly cheaper and better in every way.

They weren’t. They weren’t even close. Some, especially the Johnson variants, could boast a tiny advantage here and there, but over the long term, none were close in terms of overall durability, accuracy and reliability.

Telltale Rifle

That the rifle is still discussed, analyzed in detail and shot in competition well over a decade into the 21st century, and the names of many of the competitors are barely remembered, all by itself, pretty much tells the tale.

Had the Garand had all or most of the maladies ascribed to it, there’d be no way, eight decades later, the descendants of the prototypes, specially prepared, would even be prepared for high-power completion, or discussed with reverence. Nor would it still be winning matches once in a while against competitors designed by Gene Stone over 30 years later.

Still, a great deal of its legend is the sheer joy of shooting the rifle. My late brother-in-law, Lyman Pollock, half track driver with 2nd Armored Division in World War II, remarked, it was “fun, even for kids, and they all shot it well and fast once they got used to it.” And they did, constantly.

The valid early critiques were being diagnosed in the field. The gas trap system and seventh round stoppages were annoying enough that the company modified production techniques and also modified earlier rifles. By July of 1940, the gas port, a much older propulsion setup, was standardized, and older rifles were modified to the new gas system. Only slightly later the drawing misinterpretations that had caused the jamming issues were addressed, older receivers being precision welded and machined to the new standard.

By late summer of 1940, the M1 rifle was getting very close to the reliable, accurate, comfortable machine we know today.

By the end of World War II, Springfield Armory and Winchester Repeating Arms had produced around 3.6-3.8 million rifles. Receiver production ceased somewhere beyond 3.8 million, winding down in 1945.

No other combatant had a standard semi-automatic rifle in general service. The Soviet Tokarev and German G.41/G.43 series rifles were nowhere near as reliable or rugged, nor did they see common infantry duty.

Even the Marine Corps had, before the end of the Guadalcanal campaign, changed their minds about the rifle. They had landed in August of 1942 with M1903 Springfield bolt-action rifles, but by early 1943, had acquired M1’s and found them superior in all respects, repealing their earlier rejection and adopting the M1 as their baby.

Sold From the Beginning

How good had it been in its early form?

In the 1946 match season, using ordinary military ball ammunition, the M1’s shot scores higher than the old M1903 had before the war with some of the finest match-quality ammunition ever to leave Frankford Arsenal. Some of those scores were shot again with the older bolt rifle, and again, aggregates scores with the M1 were higher, and the bolt guns didn’t win many. The M1’s fired were “accuracy selected,” by the way, not modified, and were most often shooting against match-prepared but military-configuration ’03 specimens. N.R.A. publications noted the scores and the results. This trend continued for years until the “aught three” pretty much disappeared from military-style/open competition.

Postwar, the safety-modified operating rods were supposed to be installed on extant rifles, and all new replacements featured the inbuilt relief. The T105E1 sights replaced all earlier sights, proving so sturdy with their internal springs that even current M16/AR15/M4 receiver sights use the same principles and function identically.

Quality and strength had improved consistently at the Armory throughout the war, and even while the rifle was out of production, further progress was made.

Winchester had not kept up with quality and revision requirements during the war, but when production resumed in the ’50s, two private U.S. firms were included in planning, Harrington and Richardson and International Harvester. Having never before produced a precision product, IHC had great difficulty, resulting in several bailouts, but H&R easily adapted to production of the big military rifle. In Europe, Breda and Beretta were sent worn-out tooling, drawings and a considerable supply of parts, and began producing rifles circa-1954. The Italians continued longer than anyone else, delivering the very last Berettas as late as the 1980’s, according to some reports. The BM.59 in fact used an intact M1 receiver, slightly refashioned.

U.S. military production of the M1 Garand ended in 1956, replaced by the M14, which is a direct descendant of Garand’s rifle. Indeed, in those years when I was doing production articles, it was at Smith Enterprises International I was advised of the actual production processes, out of 1930’s machine technology. Ron Smith stated unequivocally that the production processes were such that the operating rod raceways on both rifles simply could not be formed completely by computer numerically controlled (CNC) machines. When I asked for illustrative details, Smith rattled off the names of several failed businesses that tried, already then, around 2003. The companies were entirely out of business. Reconfiguring the operating rod raceways of many aftermarket cast non-issue receivers is, in fact, still one of the recurring nightmares of shooters who purchase them thinking they are saving time and/or trouble.

Generally, the later an M1 is, the better made it is, and the higher overall quality will be. As a bonus, such a rifle has likely missed a lot of combat as well, and is likely to be in far better condition, having also missed the brutal attentions of generations of raw recruits.

The rifles have been on the civilian market since not long after World War II, albeit always priced higher than all its ordinary bolt-action contemporaries. They’re the last general-issue U.S. military service rifles that civilians can own without a nightmare of paperwork or nosebleed prices, usually both, because they are not selective fire.

Alive and Well

There are some easy rules to keeping the M1 alive and well, most of them applicable to other firearms, too.

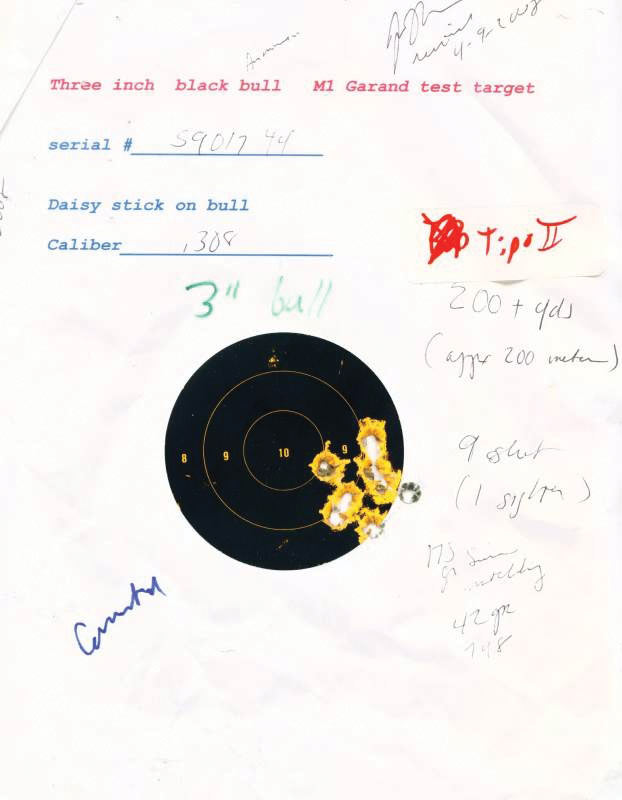

Barrel life is greatly extended if kept clean and if rate of fire is kept moderate. A service M1 barrel can last far longer than the old 6,000-round military accuracy estimate. Commercial barrels last longer, but again, keeping them clean is prudent and economical. Commercial barrels, especially heavies, are generally more accurate than service barrels, and those in .308 even more so. The newer caliber is recommended for shooters, and even more enthusiastically for reloaders. It is decidedly more accurate, easier on the rifles, and in the years to come, high quality surplus will still be available. The shorter round is also fairly close in configuration to .276 Pedersen Center Fire, the original cartridge for the M1 Garand.

The correct lubricant for heavy moving parts on the M1 and related rifles is panthermic (tolerant and usable in a wide range of temperature parameters) grease. “Lubriplate,” in fact, was invented for the M1 rifle. But newer wheel bearing greases are even better performers. I buy them in large tubs at auto parts stores for a few dollars. There are more expensive lubricants, including synthetic machine assembly greases, but they won’t work any better. Don’t use oil. It won’t work. No manual has mentioned oil for a very long time, except for the admonition not to use it. In fact, I haven’t used thin gun oils on firearms for almost 40 years, and haven’t had lubrication-induced malfunctions or heavy wood damage from oil since.

The troubleshooting charts in the detailed manuals need to be kept on hand and regarded with respect. Internet twaddle not so much. And of course one has to remember that substandard, non-issue parts, especially clips, are changing certain equations. The premature dumping of the clip along with several live rounds is correctly solved by replacement of the bullet guide and/or operating rod catch. However, if one has an out-of-specification operating rod catch, a chronically defective third-rate bootleg civilian clip, and so on, well, this difficulty can prove unsolvable. In fact, it’s smart to avoid clips that look new unless one can affirm they are G.I. marked.

Shooting unmodified wartime or prewar operating rods with the square corners illustrated here is unwise and can be expensive. Not too many years ago, a competition shooter at Rio Salado in Mesa, Ariz., told me something odd was happening with his rifle. It was binding, he said. It bore an expensive heavy barrel, was securely glass bedded, someone had done a lovely trigger job, but it bore a circa-1938 unmodified operating rod that was already showing stress cracks. I advised him the rod, even fatigued, was probably worth several hundred dollars to a collector, and that he might want to replace it with a later unit. Advising him to go some other way seemed to annoy him. He said it was original to his “DCM rifle.” He seemed to think someone was conspiring to cheat him. A few weeks later, at a high-power match, it distorted, jumped its track and partly separated. A more suitable “77” series National Match operating rod in new condition could’ve saved the match, and those could be had for about a third what his now mangled unit was worth.

An Enduring Rifle

The literature of the M1 is vast. Duff’s industrial histories cover parts appropriateness/correctness in detail. Harrison’s books contain many errors, but the illustrations are still some of the best. Hatcher’s Book of the Garand covers the rifle’s development but is by no means complete. My two volumes are for shooters, collectors, reloaders and enthusiasts, but are not intended for the kind of minute parts detail information needed to restore rifles, and are marketed as practical histories, written in an inverted-pyramid journalistic form that would be inappropriate to industrial histories. It was important to me to include the Italian rifles, since I have used and enjoyed them since the early ’70s or so, and when I initiated by projects, there was very little information on them at all. Other than the gas traps, the Italian rifles are probably the most rare of the Garand rifles. Some enthusiasts doubt there are 1,200 in the entire United States, almost all Danish-marked.

It’s imprudent, at least, to not pursue the literature of any firearm with both a shooter’s and a collector’s value. If nothing else, a late-issue manual is absolutely imperative.

My first M1, a re-milled rifle, welded together from condemned receivers, front and rear, was ordered in May of 1963 from P&S Sales. My second came some months later. I first fired an M1 about 1957.

Hitting the target is not as easy as it was a couple decades ago, but I have learned some tricks—pulling the eye back to reduce conceptual size of the peep aperture to aid discrimination, for example, when the natural tendency is to get closer and hunker down. Eyesight deterioration has taught me to shoot almost by feel, and I can sometimes equal the groups of three decades ago in very short times just from familiarity with Garand’s great instrument.

And why has the entertainment value of the rifle lasted so long?

It’s fun.

Sources for Collectors

To find out more about obtaining your own M1 Garand, the U.S. Government source for qualified individuals is:

Civilian Marksmanship Program—United States Army

1401 Commerce Blvd.,

Anniston, AL 36207

www.odcmp.com/sales.htm

Phone: (256) 835-8455

As of this writing, the CMP is the only predictable source of M1 Garand rifles in the United States. Their stock of rifles includes U.S.-produced return donations from foreign countries.

The primary source of up-to-date collector-centered data on the M1 Garand is:

Garand Collector’s Association

POB 7498

N. Kansas City, MO 64116

www.thegca.org

Phone: (816) 471-2005

While the Garand has been out of production for decades, new data about production and sometimes quality controls pops up periodically, and is often seen first in The GCA Journal. The marketplace in that publication is also an excellent source for parts.

This article appeared in the June 12, 2014 edition of Gun Digest the Magazine.

Next Step: Get your FREE Printable Target Pack

Enhance your shooting precision with our 62 MOA Targets, perfect for rifles and handguns. Crafted in collaboration with Storm Tactical for accuracy and versatility.

Subscribe to the Gun Digest email newsletter and get your downloadable target pack sent straight to your inbox. Stay updated with the latest firearms info in the industry.

![Best Concealed Carry Guns In 2025 [Field Tested] Wilson Combat EDC X9S 1](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Wilson-Combat-EDC-X9S-1-324x160.jpg)

![Best 9mm Carbine: Affordable PCCs [Tested] Ruger Carbine Shooting](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Ruger-Carbine-Shooting-100x70.jpg)

![Best AR-15: Top Options Available Today [Field Tested] Harrington and Richardson PSA XM177E2 feature](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Harrington-and-Richardson-PSA-XM177E2-feature-100x70.jpg)