I like snubnose revolvers. I mean I really like snubnose revolvers.

I like snubnose revolvers. I mean I really like snubnose revolvers.

To my admittedly antiquated way of thinking, the snubbie is the perfect self-defense gun. Semiautos get all the press nowadays, but I keep coming back to the fact that in three decades of shooting all types of guns, I’ve never had a snubbie jam, lock up or otherwise put me in a pickle. How I wish I could say the same of semiautos!

But I try not to be dogmatic about such things. If you’re carrying a semiauto right now, you doubtless have good reasons for doing so, and I would be the last person to argue with you. Really, I was only kidding, anyway — sir.

But insofar as I’ve expressed my opinion on snubbies, I might as well go whole-hog and admit that I believe the Smith & Wesson Model 36 Chiefs Special is the greatest self-defense gun of all time. It’s tiny. It’s reasonably powerful. It’s controllable. It’s utterly reliable and totally foolproof. A Model 36 in the pocket beats a 1911 left in the nightstand any day of the week.

Yet the Model 36 isn’t my favorite snubbie. That distinction would have to go to the old Colt Pocket Positive, manufactured from 1905 to 1940. The Pocket Positive has the one critical attribute that characterizes so many Colt revolvers: style. And if you can forgive me for using such a word, I might even say that the Pocket Positive is cute. Not merely cute, mind you, but cute as Brittany Spears’ … nose.

A Different Bird

The Pocket Positive was an outgrowth of Colt’s New Pocket Revolver, introduced in 1893. In addition to being Colt’s first swingout cylinder pocket revolver, this was a handy little gun, the name of which distinguished it from the “old” Colt Open Top Pocket Model manufactured from 1871 to 1877.

The Open-Top Pocket Model was a different bird from the New Pocket Revolver: a tiny little spur-trigger, single-action .22 that didn’t even have a topstrap. In comparison, the New Pocket Revolver of 1893 really was new, and with its “modern” solid-frame, double-action design, it made arch-rival Smith & Wesson’s top-break revolvers look like yesterday’s news.

The New Pocket Revolver came in blued or nickel finish with hard rubber stocks and a 2 1/2-, 3 1/2-, 5- or 6-inch barrel. It was Colt’s smallest revolver but not its only concealable snubbie, if you wanted to stretch the term a bit.

The Colt Model 1877 in .38 and .41 Colt (the so-called Lightning and Thunderer, respectively) was available in a “Storekeeper’s” version with 2 1/2-inch barrel and no ejector rod assembly until 1909.

The Model 1877 Storekeeper could conceivably be called a snubnose pocket revolver if you had pockets big enough to conceal its sizeable frame. But however you sliced it, the New Pocket outclassed every other deep-cover revolver of its day.

The original Colt New Pocket .32 had a compact, round-butt grip frame that made it especially well-suited for concealed carry. In 1896, Colt developed a variation of the New Pocket with a square-butt grip frame and released it as the New Police.

That year, the New Police was adopted as the issue sidearm of the New York City Police Department, the nation’s largest metropolitan law-enforcement agency, by virtue of the recommendation of the police commissioner, an energetic up-and-comer named Theodore Roosevelt. Roosevelt’s endorsement went a long way toward establishing the credibility of Colt’s new line of .32s.

Yet neat as the New Pocket and New Police were, they shared two flaws: They had no provision for a passive safety and were chambered for a truly rotten little cartridge.

Unique Features

Like all of Colt’s double-action revolvers of the day, the New Pocket and New Police had no safety; neither active (manually-operated) nor passive (automatic). Thus, if you dropped a loaded New Pocket or New Police .32 — cocked or not — in such a way that it landed on its hammer, the chances were fairly good that you’d go home that night with an extra bellybutton.

Then there was the guns’ chambering: .32 Short and Long Colt. These cartridges were scaled-down versions of Colt’s proprietary .38 and .41 Long Colt loads, and they shared a common shortcoming: an outside-lubricated, heel-based bullet similar to today’s .22 Long Rifle round.

The .32 Colt cartridges provided poor accuracy because they didn’t fit the bore especially well, and their exposed lube rubbed off rather easily and collected all manner of dirt and grit. (On special order, Colt would chamber the New Pocket and New Police in the much-superior, inside-lubricated .32 S&W Long cartridge, but it wasn’t eager to recognize a S&W product or stamp the hated “S&W” on its guns.)

Despite its lack of a safety and the limitations of the .32 Colt rounds, the New Pocket wasn’t a bad little gun. It was extremely small and was a much better design than its closest competitor, the Smith & Wesson First Model .32 Hand Ejector of 1896.

For one thing, you could open its cylinder with one hand, a feat that was almost impossible with the Hand Ejector. For another, you could order it with a 2 1/2-inch barrel vs. the Hand Ejector’s shortest barrel length of 3 1/2 inches.

Colt also made hay of the fact that the New Pocket’s cylinder rotated toward the frame, but those of “other” double-action revolvers (nudge, nudge) rotated away from the frame. The implication was that the other revolvers (nudge, nudge) wouldn’t stay as tight as a Colt. True? Perhaps not, but it made for a good talking point.

The New Pocket was America’s first truly modern, solid-frame snubbie. All it needed was a few tweaks, which were to come in 1905.

In that year Colt improved the New Pocket — and the New Police, too — by giving it an internal, passive-hammer block safety that prevented the hammer-mounted firing pin from falling on a live cartridge unless the trigger was held all the way back. This safety was held to be utterly foolproof or, in other words, “positive.” Thus were born the Pocket Positive and the Police Positive.

The revolvers’ chambering received an upgrade, too. Colt had realized that inside-lubricated cartridges were the wave of the future, so — no doubt holding its corporate nose — it relented and chambered the Pocket Positive and Police Positive in .32 S&W Long. But not without a fight, by gum! There was no way in heaven or earth that Colt was going to put “S&W” anywhere on its guns, so it did the next best thing: It invented a .32 S&W Long cartridge of its own.

The resulting cartridge, the .32 Colt New Police, was identical to and interchangeable with the .32 S&W Long — except for one thing. The S&W cartridge had a round-nose lead bullet, but the Colt number had a bullet with a minuscule flat on its nose. That was the entire difference.

In retrospect, it’s amusing to see how Colt avoided using the phrase “.32 S&W” in its advertising of the day. A Colt catalog from the 1920s danced around the issue on a page describing the Pocket Positive’s chambering:

“Caliber: .32 Colt Police Positive (New Police). (Using .32 Colt Police Positive (New Police); also .32 S&W Short and Long Cartridges, when the barrel is stamped ‘.32 Police Ctg.’).”

I’ve read that paragraph five times, and I’m still confused.

A Little Beauty

The Pocket Positive is simply a beautiful little revolver. Its main frame, grip frame and barrel harmonize in perfect proportions. Its barrel and extractor rod are unencumbered by a shroud, which has always seemed to me to give a snubbie an off-balance, muzzle-heavy appearance.

The Pocket Positive is simply a beautiful little revolver. Its main frame, grip frame and barrel harmonize in perfect proportions. Its barrel and extractor rod are unencumbered by a shroud, which has always seemed to me to give a snubbie an off-balance, muzzle-heavy appearance.

Finally, there’s the wonderfully sculpted cylinder latch. This latch, introduced in the 1920s, forms part of the recoil shield and was a big improvement from the angular, stamped latch that characterized Colt’s earlier double actions.

Every Pocket Positive I’ve fired has had a slick, smooth double-action trigger pull. That smoothness comes at a cost, however. The Colt’s lockwork gives great leverage but puts a lot of pressure on your hand, which sooner or later results in that characteristic last-second cylinder hitch that afflicts most heavily-used Colt double actions. Though not quite as slick as the Colt’s, the S&W Hand Ejector lockwork is much more durable.

The Pocket Positive disappeared from the Colt lineup in 1940, and its place was taken by the Detective Special and Police Positive Special. I doubt we’ll ever see the likes of the Pocket Positive again. In this day of magnumitis, the .32 S&W Long and .32 Colt New Police seem laughably underpowered. Still, whether I choose to carry one — and sometimes I do — the Colt Pocket Positive has my vote as the classiest snubbie of them all.

Glasses and shooting go together like Pamela Anderson and a video camera. You just need something covering your eyeballs. And when you reach for good glasses, you should get your hands on a pair from Wiley X.

Glasses and shooting go together like Pamela Anderson and a video camera. You just need something covering your eyeballs. And when you reach for good glasses, you should get your hands on a pair from Wiley X. American shooters and law enforcement officers have a history of being a very conventional, traditional, and at times, stodgy lot. History is replete with examples.

American shooters and law enforcement officers have a history of being a very conventional, traditional, and at times, stodgy lot. History is replete with examples. The PS90 is the civilian-legal version of the original P90, which was designed as a “personal defense weapon” for specialized military personnel whose main duties do not revolve around the military rifle. These troops are normally issued a pistol as a personal defense weapon. For U.S. forces that pistol is the Beretta M-9. These soldiers include tank or artillery crews, pilots and air crewmen, and troops operating to the rear of forward areas.

The PS90 is the civilian-legal version of the original P90, which was designed as a “personal defense weapon” for specialized military personnel whose main duties do not revolve around the military rifle. These troops are normally issued a pistol as a personal defense weapon. For U.S. forces that pistol is the Beretta M-9. These soldiers include tank or artillery crews, pilots and air crewmen, and troops operating to the rear of forward areas. This new weapon design was not to be an assault (taking the initiative) weapon, but rather a defensive (holding the position or covering the retreat) weapon.

This new weapon design was not to be an assault (taking the initiative) weapon, but rather a defensive (holding the position or covering the retreat) weapon. It is truly ambidextrous in operation, with the disk-shaped safety capable of being operated by the trigger finger of either hand, pulling it toward you to fire if you are right-handed, and pushing it away from you if you are left handed.

It is truly ambidextrous in operation, with the disk-shaped safety capable of being operated by the trigger finger of either hand, pulling it toward you to fire if you are right-handed, and pushing it away from you if you are left handed. Ok, it appeared, like I said, cool, but there were a number of things that bothered me about it. First was the price. Innovation comes with a price. The retail price is $1,500.

Ok, it appeared, like I said, cool, but there were a number of things that bothered me about it. First was the price. Innovation comes with a price. The retail price is $1,500. Founded in 1816 by Eliphalet Remington, Remington Arms Co. is the oldest arms manufacturing company in America. Before that, most arms were produced by small gunmaking operations.Remington might have marked the beginning of the industrial revolution in the gun business, I guess. It’s interesting that one of the company’s most popular products pulled it from almost certain ruin near the end of the Civil War.

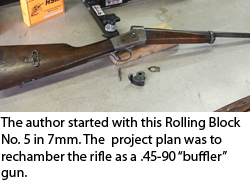

Founded in 1816 by Eliphalet Remington, Remington Arms Co. is the oldest arms manufacturing company in America. Before that, most arms were produced by small gunmaking operations.Remington might have marked the beginning of the industrial revolution in the gun business, I guess. It’s interesting that one of the company’s most popular products pulled it from almost certain ruin near the end of the Civil War. The rolling block came in various other models, but the one I found for my project was a No. 5 in 7 mm. It was a carbine and made circa 1902 to 1905. The rifle was functional, but as I disassembled it to start the project, my desire to shoot it waned. The action was in excellent shape, however, and would be an great base for my project. I began the search for the parts I’d need to rechamber it into a .45-90 “buffler” gun.

The rolling block came in various other models, but the one I found for my project was a No. 5 in 7 mm. It was a carbine and made circa 1902 to 1905. The rifle was functional, but as I disassembled it to start the project, my desire to shoot it waned. The action was in excellent shape, however, and would be an great base for my project. I began the search for the parts I’d need to rechamber it into a .45-90 “buffler” gun. After I decided on the caliber, I could start rounding up stuff. I needed a barrel, sights, a stock, a forearm and a .45-90 chambering reamer.

After I decided on the caliber, I could start rounding up stuff. I needed a barrel, sights, a stock, a forearm and a .45-90 chambering reamer. When I was ready for threading, I kept the stripped receiver nearby, as the threads were getting close. This is the only way to get a precise fit, and it takes some time to try the threads, take off a few more thousandths and try again until it screws down tight. After the fit is good, you can adjust the receiver to the right position by taking off a few thousandths at the shoulder until it stops level. The breech face will also have to be trimmed to be flush with the back of the receiver to headspace correctly.

When I was ready for threading, I kept the stripped receiver nearby, as the threads were getting close. This is the only way to get a precise fit, and it takes some time to try the threads, take off a few more thousandths and try again until it screws down tight. After the fit is good, you can adjust the receiver to the right position by taking off a few thousandths at the shoulder until it stops level. The breech face will also have to be trimmed to be flush with the back of the receiver to headspace correctly.

I'm not one for reading instructions, but it was nice to see a full-color brochure included with the new Spyderco Spyderench. This is a multi-tool to be reckoned with.

I'm not one for reading instructions, but it was nice to see a full-color brochure included with the new Spyderco Spyderench. This is a multi-tool to be reckoned with. At the other end of the unit is a nice little adjustable wrench and a slot to hold screwdriver tips. Coolest of all is the fact that you can open the knife blade one-handed without opening the tool.

At the other end of the unit is a nice little adjustable wrench and a slot to hold screwdriver tips. Coolest of all is the fact that you can open the knife blade one-handed without opening the tool.

I have three pairs, which differ mostly in size: a pair of Nikon minis, which I like for pocket glass. They are 10x40s, but are clear and get the job done without the weight of larger models. During shorter jaunts, I carry Shepherd 12x50s. Sometimes, I’ll carry them regardless because their clarity is much better. My midsize Leupold Wind River binos have been taken over by my wife, Lu.

I have three pairs, which differ mostly in size: a pair of Nikon minis, which I like for pocket glass. They are 10x40s, but are clear and get the job done without the weight of larger models. During shorter jaunts, I carry Shepherd 12x50s. Sometimes, I’ll carry them regardless because their clarity is much better. My midsize Leupold Wind River binos have been taken over by my wife, Lu. If you need that kind of magnification, get the biggest objective you can. I’ve seen high-magnification spotters with objectives that were insufficient for transmitting light — unless you were looking at the sun.

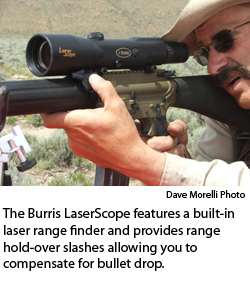

If you need that kind of magnification, get the biggest objective you can. I’ve seen high-magnification spotters with objectives that were insufficient for transmitting light — unless you were looking at the sun. Range-estimation and drop-compensation reticles are a great improvement. I learned mil-dot years ago, and it served me well. It’s still a great nonbattery system, but you must practice it to master it.

Range-estimation and drop-compensation reticles are a great improvement. I learned mil-dot years ago, and it served me well. It’s still a great nonbattery system, but you must practice it to master it. A classic handgun deserves a great holster. And sometimes, you just need something that looks sharp; something black-leather cool, like Samuel L. Jackson had in Shaft.

A classic handgun deserves a great holster. And sometimes, you just need something that looks sharp; something black-leather cool, like Samuel L. Jackson had in Shaft.

The Pioneer Gun Club Brickyard Range had served the Kansas City area for as long as anyone could remember.

The Pioneer Gun Club Brickyard Range had served the Kansas City area for as long as anyone could remember. Ask a dozen people what makes a great knife and you'll get a dozen answers. No knife can handle every job. That just isn't happening.

Ask a dozen people what makes a great knife and you'll get a dozen answers. No knife can handle every job. That just isn't happening. If you want to add a light to your shotgun, you can get all crazy with huge, bulky rails, or you can get the Tri-Mounting system from Laserlyte for about $25.

If you want to add a light to your shotgun, you can get all crazy with huge, bulky rails, or you can get the Tri-Mounting system from Laserlyte for about $25. Best, the unit practically disappears when you remove the accessories. The rails don't get in your way when you don't need them.

Best, the unit practically disappears when you remove the accessories. The rails don't get in your way when you don't need them. It seems everyone has a weapon-mounted light on the market these days.

It seems everyone has a weapon-mounted light on the market these days. The unit is also ambidextrous and comes with a super-bright LED that puts out 65 lumens. Three AAA batteries provide power for more than 50 hours of use, and the light comes with an integral clip for easy attachment to a belt or garment, eliminating the need for a dedicated light-mount holster.

The unit is also ambidextrous and comes with a super-bright LED that puts out 65 lumens. Three AAA batteries provide power for more than 50 hours of use, and the light comes with an integral clip for easy attachment to a belt or garment, eliminating the need for a dedicated light-mount holster. If you want a small gun with a big punch, get your hands on a North American Arms Guardian 380.

If you want a small gun with a big punch, get your hands on a North American Arms Guardian 380.  Sometimes, you need to break a window, which means having the right tool at the right time.

Sometimes, you need to break a window, which means having the right tool at the right time.![Best Concealed Carry Guns In 2025 [Field Tested] Wilson Combat EDC X9S 1](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Wilson-Combat-EDC-X9S-1-324x160.jpg)

![Best 9mm Carbine: Affordable PCCs [Tested] Ruger Carbine Shooting](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Ruger-Carbine-Shooting-100x70.jpg)

![Best AR-15: Top Options Available Today [Field Tested] Harrington and Richardson PSA XM177E2 feature](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Harrington-and-Richardson-PSA-XM177E2-feature-100x70.jpg)