With the right revolver skills, one can be a formidable adversary even when armed with antiquated technology.

If you’re to believe the local gun shop expert, revolvers are 19th century technology and utterly useless for anything other than making noise. When you run into someone who says this, what you do is simple: ignore him. (If he also says “IPSC will get you killed,” move to the other side of the gun shop. Staying too close to such a concentration of mall ninja-ism can be dangerous to your brain cells.)

Yes, double-action revolvers are old, but as I’ve pointed out before, the gladius used by the Roman legions is also old. If you meet someone who knows how to use it, he’ll be a dangerous adversary—even with “obsolete” technology. Skill is what matters.

So, how do you improve your DA revolver skills?

Get Good Grips

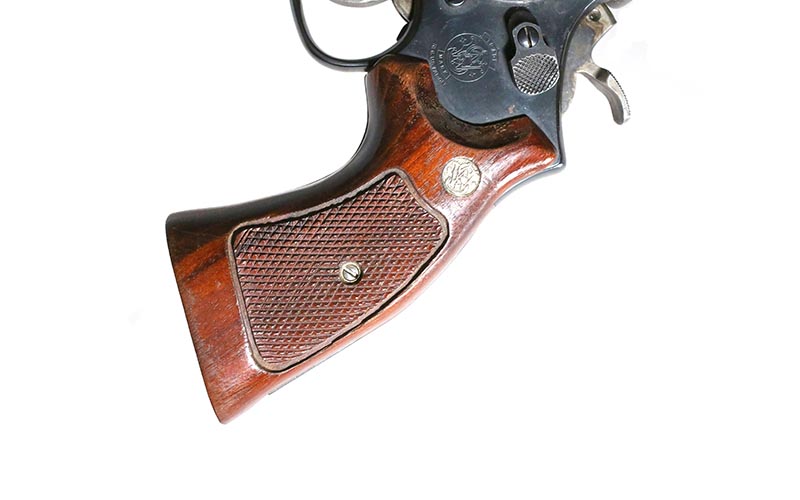

First, get the right grips. The customary, classic and good-looking ones are almost always not suited to good shooting. The classic “cokes” on a high-gloss blued S&W .44 Magnum are a beauty to look at, but they’re generally a misery to shoot.

A few good choices are the Miculek grip, Pachmayrs and VZ Grips. I used a set of Miculek smooth wood grips on my .45 ACP revolvers when I competed in IPSC. They were just what I needed to bring me home each time, with a pair of Team Gold medals to show for the trips. You can order yours checkered, but the smooth lets your hand slide on the grip to get properly located on the draw, and they’re shaped to stay in your grip when you shoot.

Here, personal preference rules. The Pachmayrs are made of rubber and that softens the recoil. They have a variety of styles to choose from. When I’m shooting pin loads or magnum ammo, I change to the Pachs, because, well, recoil hurts.

For compact carry, especially EDC concealed carry, a set of VZ Grips (they make an almost overwhelming set of choices) are just the thing—especially if you’re using a snubbie for backup or deep concealment, a VZ boot grip is just the ticket. And if you’re in a hot climate, the VZ grips are made of nearly indestructible materials.

Get a Good Grip

Second, grip it right. Take your unloaded revolver and wrap your shooting hand on it in a firing grip. Look at the web of your hand. Where is it compared to the top of the backstrap of the frame? If there’s any space between your hand and the top corner, you’re doing it wrong. Get your hand up as high as you can and still reach the trigger.

Now, if you have small hands, this might limit which revolvers you can use—but you don’t gain anything by keeping your hand down on the frame. In fact, you make recoil worse, as you give the revolver better leverage to create muzzle rise. I grip a revolver so high that some of them have the hammer touching the web of my hand as it comes back in the DA cycle.

The wrong advice is to grip lower to get your trigger finger in line with the trigger. Supposedly, pressing the trigger from an angle is bad. I haven’t seen it being bad while winning piles of loot and two Gold medals. Grip high and stay away from the guy I started this article describing.

Utilize The Clicks

When it comes to dry-firing, pistols get one click. On pistols, one striker falls and then you have to hand-cycle the slide to do it again. Despite the Foley artist (the guy who does sound effects) in movies making a pistol click repeatedly, we all know they don’t. Well, with rare exceptions, anyway. Revolvers? You can click all you want. My boss at The Gun Room, Mike Karbon, spent the slow times at the shop dry-firing his Colt Python. Click, click, click went the wheelgun…

He did this to the point that it became background noise…something we didn’t notice unless it stopped. He even broke the firing pin on one—which was unheard of—and happened so rarely that no one we called had a spare. “Those things don’t break” was the response from one pistolsmith.

You’re highly unlikely to break your firing pin either (rimfires excepted, don’t dry-fire those). You’ll get a whole lot better in the practice, and you’ll be burnishing the parts against each other that’ll slick up the action even before you pay someone to do more to it.

Learn On The Cheap

Speaking of rimfires, that’s fourth on our list. Yes, all ammo is pricey these days, but rimfire is still less expensive than centerfire. Even reloaded centerfire. So, get a rimfire, and use that as a sub-caliber trainer at the range. Yes, yes, yes, that can cost. When Jerry Miculek suggested this to me, I went out and invested in an S&W M-617 (a big help it was, too).

Yes, the MSRP on that one is just over $800. OK, let’s say that .22 LR ammo costs you $140 per thousand rounds. (With ammo prices right now, these will vary, but the relative costs won’t much.) If we only compare it to the .38 Special, currently running $650 per thousand, we can see what’s up. Bigger bores will cost even more. The cost of a .38 Special means a difference of $510 per thousand rounds fired compared to a .22 LR. As a result, you start getting your investment back after 1,500 rounds.

Yes, reloading would make the .38 less expensive, but you’re trading cash for time at that point. As prices come down, the difference shrinks, but even at the old prices, you’d get your M-617 cost back in 2,500 rounds.

So, 1,500 rounds to get your investment back. The gain after that means a lot of double-action practice at the range, at speed or for accuracy, resulting in you becoming a much better shooter.

Reload For Your Revolver

It isn’t just that loading your own ammo is less expensive than buying factory ammo (provided you stocked up on components, so you can laugh your way through ammo panics.) You can also tune your ammo to your gun and to your practice or match needs. If you need power, you can have it. If you need mild recoil, that’s simply a matter of correct loading data.

And you save money either way.

I did a quick search for components recently, and while some can be tough to find, for a .38 Special, I found powder, primers and bullets that would let me load factory-equivalent ammo for about $150 per thousand. (Hint: Buy in bulk…5,000 primers, 8-pound kegs of powder, bullets in multiple-thousand shipments.) A good press will let you load 400 to 500 rounds an hour.

At the cost savings over factory (about $500 per thousand), you’ll get your reloading press investment back in a couple of thousand rounds. I know…this and the rimfire represent an investment. But if you want to get good, you aren’t going to do it with just positive thinking.

Other Considerations

There are other things you can do, and while they do make a difference, they don’t give you the immediate return on investment that the previous tips do. Save them for later.

You can have a pistolsmith slick up your revolver—and in due time you should. But that comes after the dry-fire practice and the range trips with the rimfire. A slicked-up action improves your shooting, but only by a small amount. If you’re 2 percentage points behind the match winner, and you’re using a box-stock action, getting yours slicked up will make the difference. If you’re still working your way out of “C” class, a slicked-up action won’t make enough of a difference to get you up into “B” class.

And porting? I love the guys at Mag-na-port, but like a slicked-up action, it won’t make a difference until you’re near the top or shooting magnum loads. In some instances, it’s essential. I’m not going to shoot pins with a revolver that hasn’t been Mag-na-ported…no way. But, in my case, I’m looking to win, and I’ll have to elbow some pretty enthusiastic shooters out of the way if I’m to do so. And they’ll have all gotten the advantages they could with practice and gear as well.

I’ve made a comparison with auto racing before: You can argue all you want about what tires are best for making the turns at 220 mph, but if your skill level isn’t at the point where any tire at all will keep you off the corner wall at 110 mph, then you need to be looking someplace other than tires for improvements.

Put It All Together

So, get grips that fit and are comfortable. Learn to grip it right. Dry-fire your revolver until you can work it fast, and keep the sights buried in the center of the “A” zone or locked onto the “X” ring. Go to the range with your rimfire and validate those revolver skills in live-fire; then, beat the falling plate rack with your reloads.

Once you do that for a number of practice sessions and have started to throw your weight around in matches at the gun club, then think about having your wheelgun slicked up and ported. (If the match rules allow porting, of course.)

Skills are what win matches and fights, not just equipment—however good. Only when two competitors are evenly matched does equipment begin to enter into it. Build your revolver skills and then when you upgrade your equipment, you’ll turbocharge those skills. Technology from any century is still relevant, but only if you have the skills to use it.

Editor's Note: This article originally appeared in the August 2021 issue of Gun Digest the Magazine.

More On Defensive Revolvers:

- .357 Magnum Revolver: Controllable Concealed Carry Options

- 9 Best Concealed Carry Revolvers For Personal Defense

- Fighting Revolver Project: Smith & Wesson Model 586

- Rolling With A .45 ACP Revolver

- .410 Revolvers: Are They Really Good For Nothin’?

- Best 9mm Revolver: 5 Options For Everyday Carry

Next Step: Get your FREE Printable Target Pack

Enhance your shooting precision with our 62 MOA Targets, perfect for rifles and handguns. Crafted in collaboration with Storm Tactical for accuracy and versatility.

Subscribe to the Gun Digest email newsletter and get your downloadable target pack sent straight to your inbox. Stay updated with the latest firearms info in the industry.

![Best Concealed Carry Guns In 2025 [Field Tested] Wilson Combat EDC X9S 1](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Wilson-Combat-EDC-X9S-1-324x160.jpg)

![Best 9mm Carbine: Affordable PCCs [Tested] Ruger Carbine Shooting](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Ruger-Carbine-Shooting-100x70.jpg)

![Best AR-15: Top Options Available Today [Field Tested] Harrington and Richardson PSA XM177E2 feature](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Harrington-and-Richardson-PSA-XM177E2-feature-100x70.jpg)