We discuss some highlights from Clayton Cramer’s Lock, Stock and Barrel to learn more about the origins of American gun culture.

American gun culture is often portrayed as a modern invention, an outgrowth of industrial manufacturing, clever marketing or frontier mythology. According to this view, firearms were rare in early America, ownership was limited, and widespread civilian gun use emerged only after the Civil War.

That story is neat. It is also wrong.

The historical record tells a far different story, one in which firearms were not merely common, but expected; not reluctantly tolerated but legally required. In early America, gun ownership was not a lifestyle choice or political statement. It was a civic duty.

Few works document this reality more thoroughly than Lock, Stock, and Barrel: The Origins of American Gun Culture by Clayton Cramer, which draws directly from colonial statutes, travel accounts and original source material. The picture that emerges is unmistakable: American gun culture did not have to be invented. It arose naturally from the conditions of colonial life.

The Myth of Rare Guns

The idea that early Americans lived largely unarmed gained traction in the late 20th century through revisionist scholarship that claimed firearms were scarce and tightly regulated. Those claims did not survive scrutiny. Key works were exposed as deeply flawed and sometimes fraudulent. Yet, the narrative persisted in more subtle forms.

The appeal of that narrative is understandable. If guns were rare and socially disfavored in early America, modern gun control appears less like innovation and more like restoration. But history does not cooperate.

When Gun Ownership Was Mandatory

Colonial lawmakers did not fear an armed population. They feared an unarmed one.

In 1619, Virginia enacted one of its earliest statutes requiring men “fitting to bear arms” to bring firearms, swords and ammunition to church. Worship was not exempt from danger, and preparedness was considered essential, even in the pews.

South Carolina and Georgia followed similar paths. By the mid-18th century, South Carolina required every white male to attend church armed, with churchwardens tasked with inspecting weapons and ammunition. These laws were enforced, not symbolic.

Maryland went further. In 1641, settlers seeking title to land were required to possess a “serviceable fixed gun,” along with powder and lead. Firearms were not just tools of defense; they were prerequisites for full participation in colonial society.

These statutes reflect a worldview fundamentally different from our own. Arms were not viewed as threats to public safety. They were seen as safeguards of it.

Guns Beyond the Militia

Modern discussions often attempt to confine early firearm ownership to militia service, suggesting that guns were collective instruments rather than personal tools. But militia laws assumed private ownership. Individuals were expected to supply their own arms, maintain them and keep them ready.

Firearms lived in homes, traveled on roads, guarded farms and protected families. The same musket that might be inspected at muster was used to hunt, defend property and respond to emergencies. There was no sharp divide between “military” and “civilian” arms.

Even age restrictions cut the opposite way of modern law. Teenagers, often as young as 15, were legally required to possess arms for militia duty. There were no colonial prohibitions on youth ownership. Responsibility, not restriction, was the governing principle.

Guns, Travel and Everyday Life

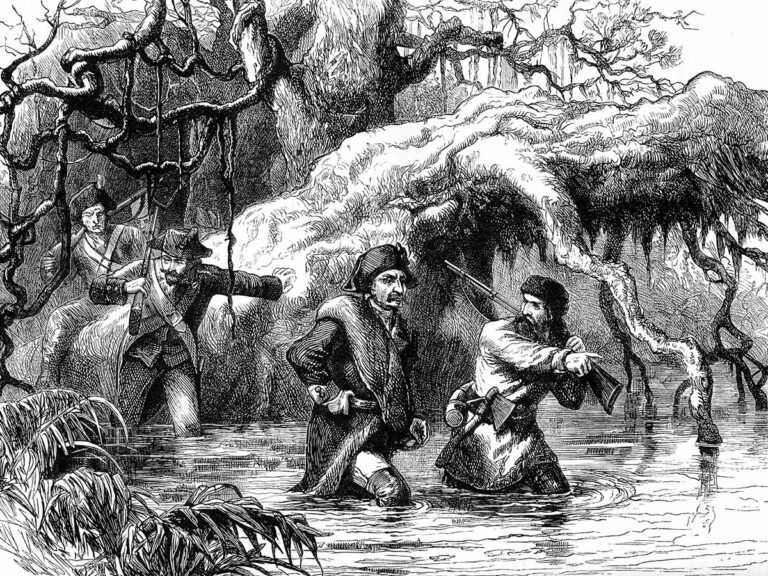

Firearms were not confined to moments of crisis or formal militia service. They were integrated into the routines of everyday life. Colonial laws frequently required travelers to be armed, recognizing that roads were dangerous and law enforcement sparse or nonexistent. In some colonies, individuals traveling alone were prohibited from doing so unless armed, while groups were expected to ensure that all members carried weapons sufficient for collective defense.

Hunting further reinforced firearm ownership and proficiency. Game was abundant, markets were limited, and refrigeration nonexistent. A firearm was often the difference between sustenance and hunger. Accounts from travelers and settlers routinely describe the ease with which food could be obtained through hunting, precisely because firearms were so widely owned and competently used.

Even indentured servitude did not break this expectation. In several colonies, masters were legally required to provide firearms to servants upon completion of their term, ensuring they could fulfill militia obligations and provide for themselves as free men. The right—and responsibility—to be armed was not reserved for an elite class. It was part of becoming a full participant in civic life.

These practices underscore a critical point often missed in modern debates: Firearms were not exceptional objects requiring justification. They were assumed necessities, woven into the fabric of work, travel, worship and community defense.

Pistols, Repeaters and Reality

Another common myth holds that early Americans owned only long-guns and had little interest in pistols until manufacturers like Colt created demand through advertising. The record again says otherwise.

Newspaper advertisements for pistols appeared in American cities as early as the 1720s. Gunsmiths routinely made and sold handguns throughout the colonies. Repeating firearms (pepperboxes and other multi-shot designs) existed well before the 19th century.

Samuel Colt did not invent America’s interest in handguns. He met a market that already existed.

Culture by Necessity

Gun culture in America was not born in boardrooms or advertising campaigns. It emerged from necessity. Colonial life was dangerous, unpredictable and decentralized. Survival required competence, preparedness and self-reliance.

Firearms were part of that equation, not as talismans, but as tools. The law reflected that reality, reinforcing ownership rather than restricting it.

Understanding this history does not require romanticizing the past. It requires honesty about it.

Editor's Note: This article originally appeared in the March 2026 issue of Gun Digest the Magazine.

More On The Second Amendment:

- End Of An Era: The Russian Ammo Ban

- Backdoor Gun Control: The '94 Norinco Ban

- Rare Breed Triggers And ATF Clash Over The FRT-15

- ATF Classifies Pot Scrubbers As NFA Firearms

- Hunting For The True Meaning Of The Second Amendment

Next Step: Get your FREE Printable Target Pack

Enhance your shooting precision with our 62 MOA Targets, perfect for rifles and handguns. Crafted in collaboration with Storm Tactical for accuracy and versatility.

Subscribe to the Gun Digest email newsletter and get your downloadable target pack sent straight to your inbox. Stay updated with the latest firearms info in the industry.

![Best Concealed Carry Guns In 2025 [Field Tested] Wilson Combat EDC X9S 1](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Wilson-Combat-EDC-X9S-1-324x160.jpg)

![Best 9mm Carbine: Affordable PCCs [Tested] Ruger Carbine Shooting](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Ruger-Carbine-Shooting-100x70.jpg)

![Best AR-15: Top Options Available Today [Field Tested] Harrington and Richardson PSA XM177E2 feature](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Harrington-and-Richardson-PSA-XM177E2-feature-100x70.jpg)