Sometimes the acts done by a country – as much as acts performed by an individual – have unexpected results. So it is with almost a of century of American presence in Nicaragua. While many aspects of the US presence are well known (most recently the confrontation with a far-leftist government in the 1980s), what is less well known is that every significant involvement the United States undertook in Nicaragua resulted in American arms of that era being imported to this small, Central American country – and then left behind.

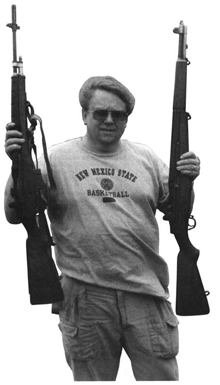

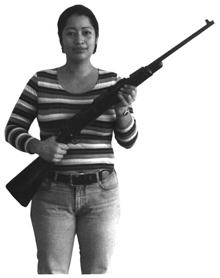

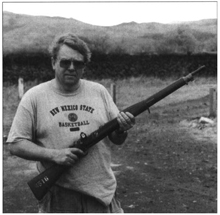

Perusing little-known nooks and crannies, usually looking for old and rare books, has provided an interesting source for aging American military weapons. And with a bit of ingenuity, sweat – and a very able machinist – I now have several of those old battle rifles – a Krag, Springfield, Garand and M-14 – up and shooting; in some cases shooting very well.

“Civilize 'em with a Krag”

When I first started hanging around gunshops back in Michigan at the tender age of about 12,1 got to know some old machinists and gunsmiths, usually of German background, who spoke English with an accent, chewed tobacco, were cranky, and knew their business. Chronologically, that was about the end of the Eisenhower administration; a world much simpler, when most gunshops were awash with old WWII gaspipes – and some older pieces, like the Krag. I remember selling from the gun rack several sporterized Krags for $25. The word, from my tobacco-chewing mentors, was that they were a ‘smooth action' but pretty old and therefore not worth much. Also, even in those days, there were a lot of Krags with rotted barrels. There was still floating around some of the original GI ammo with corrosive primers that would frost a barrel overnight if it wasn't cleaned with soap and water soon after shooting. Still in all, I liked the Krag, especially when loaded with the venerable Lyman cast bullet design #311284. I decided one day I would have one of those elderly rifles.

Fast-forward through the decades to a time much later. in the spring of 2000 I was in Masaya, a regional town about 20 miles from Managua, looking for some old books. There had been a series of earthquakes caused by a local volcano that had shaken up many of the old adobe houses. People began cleaning out their back rooms and selling a few things. Quite by accident I found a house where the owner had an old collection of very rusty rifles. In looking them over, they appeared to be a collection of rifles that had been used in every revolution (of which there have been many) – successful and unsuccessful – since the 19th century. The collection began with an Erfurt Mauser Model 71/84, a Remington rolling block 7mm, a Model 1916 Spanish Mauser, a rusty (but still functioning) Model 1892 Winchester in 32-20, and a couple of really rusty Krags – one with bolt and action intact, but missing most of the furniture. The barrel was so rusty, light would barely shine down it. As usual, I paid too much for that piece, went next door to my favorite Mexican restaurant and celebrated with some fine mole.

The stock had termites, but I gassed them and found that with some judicious glass bedding I could make that stock work again, especially as a carbine. The major problem was the barrel – it simply had to be replaced. I soon found that Krag barrels in good condition are just about impossible to find. Even William Brophy's fine The Krag Rifle proved to be of little help in obtaining the dimensions of the Krag barrel at the shank end, where everything mattered.

In desperation I e-mailed Brownells and asked their advice. I said I wanted to communicate with an old, cranky gunsmith, who chewed tobacco and who remembered how to rebarrel a Krag. Four days later I got a response from old Reid Coffield, member of the staff of Brownells and gunsmith extraordinaire. He said he did not chew tobacco but otherwise met the bill as he was pretty old, remembered perfectly how to rebarrel Krags, and surely was cranky. Aha! I thought, a blast from the past. As one would figure, the Springfield barrel shank is really quite close to the Krag's, with a slightly different diameter and pitch of thread. Also, the extractor cut in the Krag barrel is on the top and completely unlike that of the Mauser-type Springfield. And, the chamber of the 30-40 Krag is different enough from the 30-06 so that it had to be rechambered if one used a Springfield barrel.

I found, in the old bodega of Somoza's army, a couple of Springfield barrels and so had only to find a machinist who could do the work that ‘Doctor' Coffield suggested. As it turns out, the tropics had an allure not just for me, but also for a semi-retired master machinist Catalunian, Don Jose Sanchez. Hailing from Barcelona, long Spain's manufacturing center, Don Jose simply knew his business. In his front room he has a large lathe, and he can make most anything out of metal that is required. I gave him the rusty Krag, the barrel, a chambering reamer for 30-40 Krag, a translation of ‘Doctor' Coffield's missive, Brophy's book -and a week later I had a Krag barreled action with a new barrel.

I specified that I wanted him to duplicate the Model 1898 carbine, complete with a 22-inch barrel and cut-down stock. He was able to cut down the stock, plug the termite holes, form a new handguard and braze on the original front sight -all without breaking into a sweat. The rear sight is still the 2nd model of the Model 1902 rifle sight, but I can live with that. I have not installed the saddle ring as they make noise and I use this carbine for deer hunting down here.

At the range, the virtue of a new barrel tightly bedded into the stock became apparent as, from the first, the carbine grouped 1 inches at 100 meters. The load? An FN 30-caliber 147-grain FMJ in front of a reasonable charge of 4064. Velocity? Probably 2400 fps. The result? A fine deer rifle that shoots well and handles surprisingly well. In fact, the Krag carbine, with its 22-inch barrel and shortened stock, handles very nicely, much like the trapdoor Springfield carbine. It is simply a lovely carbine, and one that is a pleasure to shoot. It would be at home in the forests of my native Michigan or in the black timber of the Yellowstone country, and would make a dandy rifle for the hunter that wants to put the hunt back into hunting and leave his ‘digital' rifle at home.

The M1903 Springfield in Action

As much as anything, Paul Mauser's Model 1898 bolt-action 8mm spelled the end of the Krag's career in the United States Army. By 1903 the Army had adopted a modified Mauser action that retained some of the lines and furniture of the Krag. The quaint side box magazine was changed into a conventional Mauser-type staggered box magazine fed by 5-round stripper clips. The action was straight Mauser, with the distinctive knurled cocking piece retained from the Krag. The barrel was set at 24 inches in length and the sights included a modified late-model Krag rear sight calibrated for a 30-caliber bullet of 150 grains at about 2750 feet per second.

The result was a rifle that was surprisingly light and that made a very fine target rifle. For horse cavalrymen like Col. Frank Tompkins, who led the chase after Pancho Villa after his raid on Columbus, New Mexico in 1916, the M1903 was a bit long for cavalry use. Later, writing of the incident, he evaluated the equipment he had used in north and central Chihuahua. He noted, regarding the rifle, “The present rifle[the M1903 Springfield] is too long and too heavy for the cavalry. I suggest a carbine about the size of the old Krag carbine chambered to shoot same ammunition as the infantry rifle.” (Tompkins: 235).

Still, the Model 1903 did have an interesting moment at the little-known encounter at Hidalgo de Parral. Known as the place where Pancho Villa was assassinated in 1923, in 1916 it was the scene of one fine shot by a good rifleman and a Springfield. Col. Tompkins and his mounted troopers had just been run out of Parral by irregular Mexican cavalry. The Mexican troops stopped on a hill about a half-mile from the Americans and appeared to ponder what to do next. One Captain Lippincott, a member of Tompkins' squadron, laid down on top of an adobe house and prepared to fire at one of the horsemen, a target he calculated to be 800 yards distant. He adjusted the Springfield's sights, slipped into the prone position, correctly used a tight sling and, with one shot, dropped one of the cavalrymen from his saddle.

In Nicaragua, the era when the Springfield spoke was the Marine intervention to fight against Cesar Augusto Sandino, 1927-1933. Much has been written about this guerrilla action, and much of what has been written is a bit fanciful. Total Marine casualties in the field for that six-year period were 43 dead; more died in brothels, barroom brawls, of disease, and suicide than died on the battlefield.

In the field the Marines used two weapons, the M1903 and the M1921 Thompson sub machine gun. The native troops were given the Krags. Due to the heavy growth on many of the mountains, the arm of choice of the Marines was the Thompson. Probably the last Marine living in Nicaragua was Mr. George Smith. He was the Marine provincial commandant of Esteli while his friend Chesty Puller was the Marine provincial commandant of Matagalpa, the next province to the east. Interviewed by the author in 1991 a month before his death, old George was emphatic that he went into battle and ambushes with a Thompson with four 50-round drums of ammo and left his Springfield at home. He was never sorry.

Still, the Springfield had its uses; one imaginatively applied by Matthew Ridgway, in the 1930s a young officer on duty at Managua. He developed a passion for hunting the Central American alligator, or caiman, that abounded in the waters of Lake Managua. He evidently spent many a happy afternoon crawling through the mud on the shores of Lake Managua drilling caimans with the Springfield. He even lost his West Point ring in that slime.

A more important use of the Marine Springfields occurred in the July 16, 1927 Sandinista attack on the Marine headquarters in the northern mountain town of Ocotal. The Marine commander, one Capt. G.D. Hatfield, with 34 Marines under his direct command, entered into an exchange of telegrams with Augusto Sandino a few days prior to the attack. The exchange ended with Sandino writing, “I remain your most obedient servant, who ardently desires to put you in a handsome tomb with beautiful bouquets of flowers.”Hatfield replied,” Bravo General. If words were bullets and phrases were soldiers you would be a field marshal instead of a mule thief”. The attack came a couple of days later; with hundreds of Sandinistas attacking the Marine barracks in the town hall (and the town hall of Ocotal still today). The Marines fought off the Sandinistas with a couple of BARs, but mostly Springfields. The native troops, the nascent Guardia Nacional, were holed up two blocks away and fought off the attackers with their Krags. The fighting was fierce and the Marines were in a difficult position until a couple of Marine bi-planes flew up from Managua, saw the situation and returned to Managua for reinforcements. By middle afternoon five DeHavilands appeared over the Sandinista troops and began dive-bombing the troops, dropping small bombs. The air attack lasted only 45 minutes but it broke the back of the Sandinista attack. It also wrote a new page in military history by being the first organized dive-bombing attack in history, years before the German air force was credited with inventing this new use of the, warplane.

By chance I ran across remnants of a Springfield, built by Rock Island Arsenal. As usual, the barrel was rotted out, there was no stock, and the action was not exactly in mint condition. No matter, I checked with all of the gun repair shops in Managua and found the parts I needed: a stock, and a barrel in good shape. Again, old Don Jos? Sanchez came to the rescue and installed the barrel. I did the rest, installed the stock, handguard and furniture, glass-bedded the action into the stock, and put on a Lyman aperture sight, much lamenting they no longer make the great #48 sight. The result is what you would call a parts gun, but one that had the potential to shoot.

More interestingly, the action was made at Rock Island Armory, with a serial number of 374XXX. That rifle was made at – or shortly after – the end of WWI and may have taken part in the Marine activities in the U.S. intervention of 1929-1933. At least the serial number is correct for that period. And, judging from the deep pits in the action, that rifle had been in tropical America for a long time. Unfortunately, when I took the rifle to the range to test-fire it, I could not get it to shoot worth beans. I then had to enter into the voodoo world of Springfield bedding.

There are (or were, since few people still shoot the Springfield in its military condition – and especially at 300 meters, as was my intent) two schools of thought on Springfield bedding. One school, represented by the eloquent writings of Col. Townsend Whelan, argues for a free-floating (more or less) barrel within the military stock, including the handguard. The other school of thought was impressed on my tender sensibilities by some of the old WWII vets that shot at the local rifle club and who, in the early '60s were in their 50s. One old boy, Salvatore, told me that Springfields always shot better with a lot of upward pressure on the barrel under where the front band and bayonet lug was located. He told me to hang a coffee can of lead shot under the front of the stock and apply glass-bedding so that when the glass ‘set up,' constant pressure upward on the barrel would dampen barrel vibrations and improve accuracy.

On my second foray into glass-bedding with Brownell's original recipe, the kind you had to add in the glass fibers and dye powder -and that set up with a puff of smoke, I got the job done but it did not look good. My father, who thought my brother's and my enthusiasm for guns was a perversion of youth, found the sight of my Springfield, dripping that runny glass-bedding onto the floor – and with a coffee can of lead shot hanging from the front of the stock, complete with glass fingerprints all over the rifle -a funny sight indeed.

That was my first experience with what ‘Professor‘ Jerry Kuhnhausen calls ‘mechanical locking.' After not so gently separating the stock from the action and getting rid of the hard drips of glass, I took the rifle to the range. I found that Salvatore was right because that Springfield would really shoot and keep all of its shots inside of the old 5-ring at 300 yards, with many in the 5V-ring.

orty years later I found myself in the same predicament. I forwent the coffee can treatment and decided to use shims and a system of bedding that I found that worked on an old Model 52 Winchester and the 7.62 54Rmm Nagant carbine. The Winchester was one of the first ones, without the speed lock, and was bedded – mostly – with a very tight front barrel band and a tight forward screw. The action was almost loose in the stock. That old rifle would shoot inside of an inch at 50 yards with iron sights, with many groups approaching a half-inch. The Nagant was bedded the same way, with the barrel completely shimmed so that it could not flop, or vibrate very much at all.

I took the Springfield to the range with some file folder shims and tested out a couple of thicknesses until the Springfield began shooting sub-two-inch groups at 100 meters, with a couple groups approaching one inch. The accumulated thickness of the shims was 0.015 inches and the barrel within the front band was tight. I then substituted tuna fish tin-can shims for the paper shims – cut to the same thickness – and went back to the range. The Springfield easily shot into 1 1/2 inches on a regular basis. With a 100 meter ‘zero' the Springfield is sighted for the NRA 300-yard slow-fire target with 23 clicks elevation on the Lyman #57 sight. The Springfield, silent for over 70 years, was again honorably punching holes – in paper – in Nicaragua.

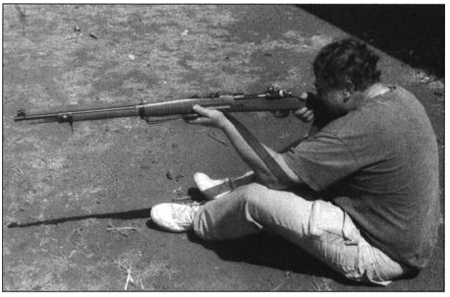

In the newly-ordained rifle matches down here held at 300 meters, shot from the sitting position and using the NRA 300-yard slow-fire target the Springfield, using old ball ammo, holds its own against the newer Garand and M-14. And, it is a pleasure to hear the bark of a Springfield that has been down here for almost 80 years and see the precision with which it can still punch 30-cali-ber holes in a target more than three football fields away.

The M1 Garand

During the long, sleepy 40-year interlude of the Somoza family's political control of Nicaragua the prevalent arm of their army, the Guardia Nacional, was the M1 Garand. All of them were supplied by the United States. The Guardia carried their Garands everywhere. Later, after the Sandinistasdrove out Somoza in 1979, the arm of choice became the AK 47 and the Garands were relegated to guard duty, and finally oblivion. In fact, in the last 10 years it has become hard to locate an intact Garand. After some considerable efforts I located two junkers and began to rebuild them. As with the Krag and Springfield, the barrels were rotted and some parts inside were broken or missing. For some reason, both had parts of the rear sights missing, and the top of the safety lever broken off.

I must admit that I had, for years, a prejudice against Garands. While a young lad, I began sighting-in rifles for deer season at the local gun shop and had the opportunity to get to know many different rifles. At the range I never could get a Garand to group better than three inches, and I thought that all Garands were mediocre in the accuracy department. Then one day I had that youthful illusion shattered. While at the 300-yard range test-firing an FN 270 Winchester, I noticed that one Johnny Zajac came to the firing line with a Garand in good shape. Old Johnny was the city plumbing inspector, spoke English with a plainly Polish accent, and always chewed cigars, usually unlit. But old Johnny could shoot. I watched him, from the sitting position, shoot 10 rounds in one minute with his Garand. I then drove him down to the target and saw nine shots in a circle of about three inches, with one shot that had ‘leaked' two inches outside of the group. He was furious with that leaked shot and used cusswords in both languages. I became converted to the accuracy possibility of the Garand.

In Nicaragua, parts for the Garand can still be found locally and I rebarreled both rifles. Since, like the Springfield, I intended to use both rifles for high-power target shooting at 200 and 300 meters, I had to do something to improve their 4-inch groups. The answer was simple. I bought one of the first copies of ‘Professor' Jerry Kuhnhausen's book on accurizing the Ml and M14.1 read the book several times and went to work. The result was two highly accurate Garands that will shoot 5- to 6-inch groups at 300 meters, with the ‘issue' iron sights. And they will probably shoot better than that, but my eyes don't see the front sight as clearly as they once did.

‘Professor' Kuhnhausen's theory is that by tightening up everything that hangs from the barrel, including the entire gas system (and ensuring the gas system hangs directly under the barrel assembly, what he calls centerlining), and by glass-bedding the action into the stock so that it is drawn down tightly into the stock by closing the trigger guard, the Garand will shoot as well as any bolt gun and do so for many rounds without changing point of impact. One of his secrets is ‘pressure bedding,' or glass-bedding the action in such a fashion that the barrel is flexed downward by some 25 to 40 pounds of pressure. Obviously, with the gas system, one cannot speak of a free-floating Garand barrel, so the service armorers began to experiment with ways to dampen barrel vibration – exactly as I had done with the Springfield. Their solution – and Kuhnhausen's -was to apply Rube Goldberg technology. A small fixture is made and placed under the barrel so that, when the action is glass-bedded, the back of the action must be forced down to the stock – by either a clamp, fixture or surgical elastic tubing. It really looks weird but it works like gangbusters.

The result is a rifle that must be assembled with some force, but which will not change its point of impact even under repeated shot strings. It changes the Garand from being a run-of-the-mill battle rifle, that will group 3-4 inches with a good barrel, into a precision instrument that will group between 1-2 inches – even with the half-century-old ball ammo that I shoot – and not change its point of impact, regardless of barrel temperature. The Garand becomes every bit as accurate as the Springfield.

The M14

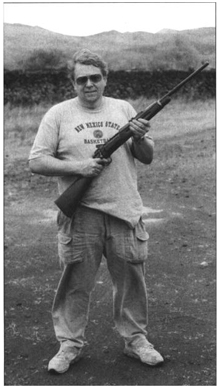

The last of the American battle rifles commonly found in Nicaragua is the M14. How it came to Nicaragua has to do with one of the more colorful Contra commandantes, Eden Pastora, “Commandante Zero.” Never one to suffer from an inferiority complex, during a couple of years in the Contra War he had considerable support of the United States government. He was known for his unorthodox manner of waging war. For example, he would perform amorous interludes with known Sandinista spies in the hopes of converting them by means of his prowess. He also had the Contra headquarters with the most information leaks. When he decided to attack the southern border town of Greytown in the middle 1980s, he scrounged a bunch of M 14s from some American warehouse, some in almost-new condition. The Sandinista Army, of course, knew all about it and confiscated the arms cache of about 1500 rifles. A decade later many of them were sold to Century Arms. A few of those rifles made their way into civilian hands and the Nicaraguan army retained a small amount.

I was asked to accurize several M14s and so I turned to ‘Professor' Kuhnhausen again. In dissembling the M14 it occurred to me that it is nothing so much as an Ml with a much-improved gas system and with the ability to accept a magazine from the bottom of the receiver. That's about it. It does have a selective-fire switch, but that is about useless as the cyclic rate is so high that it climbs uncontrollably. Should one have any doubt of its limited use as a machine gun, try firing a G-3 on full auto – and then the M14 – and it becomes obvious that the G-3 has a very useful rate of fire and the M14 just wastes ammo. Moreover, the M14 is made completely of forgings and has no stampings. It is one fine rifle.

To accurize the M14, the exact same theory that was useful with the Ml can be applied. The process involves tightening up the gas system in relation to the barrel, and pressure-bedding the barreled action tightly into the service stock with adequate ‘draw' from the trigger guard. In fact, of all three American battle rifles the M14, at least to me, is the easiest to accurize. And they really do shoot. From the bench, with iron sights, several that I have worked on will group 5-7 inches at 300 meters. And I am sure that younger eyes could improve on that grouping, seems to shoot best with either FN ball ammo or Portuguese ammo that was imported into Nicaragua in the early 1980s. And, like the Garand, when properly glass-bedded the point of impact does not change in slow- or timed-fire. As good as is the Garand, the M14 is a bit better.

Regarding Ammunition, Ergonomics, And Rifle Use

One of the more interesting, but little-known facts about the 30-06 and 7.62mm NATO rounds is that they are ballistically identical. Frank Barnes, some time ago, collected all of the ordnance data on U.S. military cartridges, including powder charges, and found that the standard load was a 150-grain (or thereabouts) bullet traveling at 2750 feet per second at the muzzle. That appears to be the case from WWI, except for a time when the M72 bullet of 172 grains with a boattail was substituted for the 150-grain ball. The common charge was 50 grains of 4895, a hotter load than found in modern loading manuals. That load became the standard load for WWII and afterward; when the 7.62mm NATO was adopted in 1957 it was loaded to the same, exact ballistics – which leads to some unanticipated advantages.

For example, when the Ml is sighted correctly to shoot off the front sight at 100 yards and the rear sight is indexed on the 100-yard setting, the ability to sight for longer distances is made very easy with the aperture rear sights, which have one-minute clicks and are calibrated to distances past 1200 yards. The sights on the M14 are almost the same, being set for 100-meter intervals and the clicks being one minute at 100 meters, rather than yards. But they are set up the same fashion as the Garand sights. And since they shoot equal weight bullets at the same velocity, the trajectory is the same.

At 300 meters, and shooting at the 18-inch bullseye of the 300-yard slow-fire target, my sight setting, using a 6 o'clock hold, for the Garand is the 300-yard setting, plus three clicks. The center of the target is nine inches, or three minutes of angle, above the point of aim. Ditto for the M14, where my sight setting is also the 300-meter setting, plus three clicks. No other battle rifle known to me has this facility for changing sight setting, or returning to an old sight setting, with no change in point of impact.

After going through the exercise of reconditioning old American war-horses, the inevitable question is which rifle shoots the best. In answering the question, some consideration should be given to the type of shooting in which the rifles have been used. The Springfield, Garand and M14 all have been used with iron sights in offhand, sitting, and prone positions; the last two positions with a tight sling. The common range has been 300 meters at the Nicaraguan regular rifle matches, and the target is the NRA 300 yard slow-fire target. The Krag sits in a class by itself. It is a fine offhand rifle – period. Of the four American battle rifles, it handles most like an American sporting rifle. It is my choice for hunting the small Nicaraguan whitetail deer in thick forest. Its smooth bolt action is unparalleled and it is the most fun of all the battle rifles to use to kill rocks and tin cans. And it is, to my eyes, the most nostalgic and attractive of all American bolt-action rifles. No gun collection can be complete without a Krag.

For me, the Springfield is the most difficult rifle to shoot, for two reasons. First, it is the lightest, making it very easy to throw a shot into the white, or beyond. Secondly, its stock has a lot of ‘drop' and so the recoil, during a shot string, is more noticeable than with the other two rifles. The Springfield has the most nostalgia and the best trigger – but I don't shoot it as well as the others, I am sad to say.

The Garand is muzzle-heavy and some days seems to just go to sleep under the bullseye. My Garand has a better trigger than the M14 and the scores I shoot with it and the M14 are almost identical. But I average a few points more with the M14 than the Garand. Why? I dunno. Finally, when the pressure of a match approaches and my friends all become enthusiastic competitors, I reach for the Winchester M14 that I got, courtesy of some governmental agency and Eden Pastora. It is the first M14 that I ever glass-bedded and I made a bunch of mistakes in that first attempt. But occasionally I will get a one-inch group from a benchrest at 100 meters, and at 300 meters I can call almost every shot – even the bad ones that go wandering toward Masaya volcano. It is a bit lighter towards the muzzle than the Garand and should be a bit more difficult to hold steady from the sitting position. But it is the rifle that somehow shoots the best for me, and in which I have confidence. It goes to every match and always shoots better than I. It is much rifle.

Lastly, a few words are in order about modern rifle use. One of the biggest impediments to getting shooters to participate in the Nicaraguan national rifle matches has been “shooter shock” at shooting at 300 meters and shooting with iron sights. Many of my friends read English-language gun magazines, reload and can quote the latest article about the 300 Dragon Killer Diller that shoots a 150-grain bullet at almost 4000 fps. They also are adept at benchresting such flamethrowers at 100 meters, and discussing the fine points of pillar-bedding, rifle powders, etc. But get them off the bench, suggest they learn to use a sling and shoot at 300 meters – and some folks become plainly nervous. When some folks try shooting at the bullseye with scope sights, they discover that the scope is not necessarily superior sighting equipment, if you have a fixed point of aim for iron sights and those iron sights are properly sighted in. With its image vibrations the scope may actually be a hindrance.

Times change and fashion changes. The old riflemen at the Bay City Rifle Club that got me shooting decades ago are long departed. Somehow the idea of teaching the basics of rifle shooting with 3- or 4-position shooting of the 22 long rifle at 50 feet got lost in America, as did the idea of shooting high-power rifles – using the same theory of position, sight alignment and trigger control – as for the 22 rimfire. The use of the tight sling becomes almost a lost art. More velocity, synthetic stocks, and other innovations cannot replace the pure theory and practice of rifle fire, and no medium has reduced rifle fire to its essence, or to its classic simplicity, as does shooting the American battle rifle from position, at extended ranges and with iron sights. ‘Digital' guns have their use, and are now most popular, but somehow the magic and skill of directed rifle fire has gotten lost in technological developments. A return to using American battle rifles, those dependable warhorses, so much a part of the American past of target shooting and history, should once again become a part of the present and future of shooting. There can be no more elegant use for a centerfire rifle.

For further Reading:

Brophy, Lt. Col. William S. USAR Ret. 1985 The Krag Rifle, The Gun Room Press, Highland Park, NJ

Kuhnhausen, Jerry 1985 The Gas Operated Service Rifles A Shop Manual, Volumes I&II, VSP Publishers, McCall, ID

Macaulay, Neill 1985 The Sandino Affair, Duke University Press, Chapel Hill, NC

Tompkins, Frank, Col. 1995[1934]

Chasing Villa,

J.M. Carroll & Company, Bryan, TX whelen, Townsend, Col. 2000[1946]

Looking for the best scope for m14 sniper rifles? Need an automatic ranging scope for your M1A? Check out this sniper scope review of the Leatherwood ART scope (Automatic Ranging and Trajectory).

Next Step: Get your FREE Printable Target Pack

Enhance your shooting precision with our 62 MOA Targets, perfect for rifles and handguns. Crafted in collaboration with Storm Tactical for accuracy and versatility.

Subscribe to the Gun Digest email newsletter and get your downloadable target pack sent straight to your inbox. Stay updated with the latest firearms info in the industry.

![Best Concealed Carry Guns In 2025 [Field Tested] Wilson Combat EDC X9S 1](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Wilson-Combat-EDC-X9S-1-324x160.jpg)

![Best 9mm Carbine: Affordable PCCs [Tested] Ruger Carbine Shooting](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Ruger-Carbine-Shooting-100x70.jpg)

![Best AR-15: Top Options Available Today [Field Tested] Harrington and Richardson PSA XM177E2 feature](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Harrington-and-Richardson-PSA-XM177E2-feature-100x70.jpg)