At what point does a gun stop having serious collector value, and become more valuable as a candidate for restoration? Follow a Winchester Model 1886 from the dusty confines of the past to a whole new life.

The shabby old Winchester Model 1886, when it came into my possession, was almost indescribable. It could have been a good one: Chambered for the highly desirable 40-65, with an octagonal barrel, fine bore and clean internal mechanism, the rifle should have commanded a premium price. Instead, it was going for less than half of “book.” There was no need to ask why.

At some point during its century on this earth, the hapless firearm had fallen into the hands of a man with a jack-knife, artistic pretensions and far too many long winter evenings. The result was, well, almost indescribable.

“Thirteen hundred and it's yours,” Jeff said. “Sad, isn't it?”

“Maybe,” I replied, studying the sacrilegious carvings and the pitted frame. “But then again, maybe not.”

As I wrapped up the old warrior and carried it gently from the shop, I could have sworn I heard a whimper of relief.

Learn More About Legendary Winchester

To my mind, Winchester Model 1886 #121321 was a prime candidate, not just for some cosmetic repairs, but for a full-scale restoration as only Doug Turnbull can do. Not refinishing, not even what is called refurbishment, but complete, historically accurate and authentic restoration: Returning the rifle to the exact condition in which it proudly left New Haven in May, 1900.

Restoration! I can hear the gasps as Winchester collectors from coast to coast start dialing the nearest exorcist. You mean alter an original 1886? A collector's item? Yes, and no. Yes, we'll alter it, and no, it's not a collector's item – at least not one worth preserving.

Right there is the key phrase: “worth preserving.”

At what point does a gun stop having serious collector value, and become more valuable as a candidate for restoration? A look at any book of suggested gun values shows how the value drops off quickly, from new-in-the-box, to mint, to 98 percent, and on down. When a rifle is judged to be about 75 percent condition, with the bluing gone, collector value (except in the rarest cases) is really little more than you might pay to get a gun for hunting, shooting, or cowboy matches.

Is that condition worth preserving for posterity? I think not.

All of us have seen rifles that have been “refinished” (and often refinished poorly.) These sell at a discount even to an original rifle in poorer condition, and rightly so. The lettering is faint and uneven, sharp corners are rounded off, and the bluing is modern and nondescript. Often, stocks are sanded so much the buttplate protrudes on all sides. But that is refinishing by amateurs. It is not restoration, and authentic restoration of firearms is the subject here.

Americans as a people are preoccupied with collector value, not just in firearms, but also in many other fields. The fear that any kind of repair will damage collector value has relegated many a fine gun to a reluctant home over the fireplace, or resulted in its being traded for something more modern. Giving up the pleasure of using a fine old rifle to hunt deer in exchange for a new contraption with a shiny barrel, a plastic stock, and no character, all in the name of collector's value, strikes me as a very poor bargain.

The key question is whether this abhorrence of alteration is legitimate. After all, there are areas of equally obsessive collection (and much bigger money) where restoration is not only accepted but, when properly done, actually adds value.

Antique automobiles are the prime example. Any car that was ever used cannot be “factory original.”Oil gets changed, tires wear out, and carburetors, windshields, and headlamps are replaced. This is normal maintenance. The key to auto restoration is to restore it to original condition, meaning that everything is as it once was or might have been. Tires must be authentic, and even the paint color, enamel, and application method must be historically correct. The result, when done properly by experts, is a car that is letter-perfect in both condition and features.

These restored automobiles win jet-set competitions, change hands for millions, and grace the most exclusive collections. The critical consideration is authenticity. So if this is true of vintage Ferraris, and accepted without question, why not vintage Winchesters?

Robert M. Lee is a prominent collector of both firearms and automobiles, one of a handful of men on the planet who is a genuine expert in both fields at the highest level.

“To a serious gun collector, condition is everything,” he told me. “The difference between cars and guns is that there are many more guns in fine to pristine condition, even guns hundreds of years old, than there are automobiles. Automobile collectors really do not have a choice, because mint original specimens are so rare.

“When it comes to gun restoration, there are two principles. If a piece is in fine condition it should not be touched; and, if a piece is extremely rare or one of kind, it should not be touched regardless of condition.

“If you have a gun that is in shabby condition, and there are thousands of them around – the Winchester 94 is a perfect example – then proper restoration will give you a really nice example of a rifle you otherwise could not afford.”

Bob Lee says he has “great respect” for a gunmaker who is capable of restoring antique firearms. Most of them are in Europe, and they ply their trade for museums and collectors, like Lee, who operate in the stratosphere of collecting. Lee ranks Doug Turnbull in that group.

“I have seen his work. His case-hardening is excellent, excellent. There are so few people who know how to do that, and most are in Europe.”

Although he avoids restored firearms in his own collection except for a few special circumstances, Lee says it represents another class of collecting, and one that is growing.

In the case of my Winchester 1886, such concerns simply did not matter. To me, the rifle was an abused puppy to be rescued. The anguished howls of the local Winchester aficionados rang in my ears as I settled down to do something about the execrable condition of poor old #121321.

The first step was a call to Doug Turnbull, followed by photos of the rifle, close-up and from all angles.

“Sure we can do something,” Doug said. “What about the stock, though&?”

“We'll re-stock it. Nothing can save the existing one.”

“Yes, it's too bad,” he replied. “It was a nice piece of walnut.”

“Yes. Was. I'll get you a blank.”

The goal was to return the rifle to the look it had when it left New Haven. That means a piece of walnut typical of the period. Although black walnut was standard on American rifles of the time, it was not absolute. What was important was avoiding a piece so showy as to be out of place. Gorgeous walnut looks at home on a Holland & Holland, but simply wrong on an old lever action.

Bill Dowtin is a dealer in-stock blanks and a stockmaker of more than 30 years experience. Now an importer of walnut from central Asia, Bill prides himself on being able, not just to judge a blank, but to match the character of a piece of wood to the intended gun. I explained the situation.

“Don't worry,” Bill said, “I'll get you a suitable blank. On those rifles, they liked walnut that was very red. Some were feather-crotch, but most were cut one or two slabs away. It is hard to describe the figure. Almost an irregular anomaly type of figure. Mottled is about the best term for it.” His description meant little to me at the time, but the finished product certainly did when I saw it several months later. But all that was to come.

I sent the rifle to Turnbull Restoration where operations manager Jason Barden logged it in and began a thorough assessment of its condition. The first step was to determine exactly what it had been when it left the Winchester factory in May 1900. A letter to the Cody Firearms Museum in Wyoming (custodian of the Winchester records) gave us a slight shock.

“When the rifle left the factory it was not a 40-65,” Doug told me, “It was a 38-56. It is not even factory original now, and there's no way of knowing when it was rebarreled, or by whom. He did a good job, though. It has a good bore. And it is a Winchester barrel.”

There was really nothing to be decided. I liked the rifle as it was, and 40-65 brass is easy to come by these days compared to the arcane 38-56. To my mind it all just added to the rifle's charm and mystery.

“We'll get a letter from the museum but leave the rifle as it is.”I said. “Whoever owns it 50 years from now will appreciate it.”

So, ironically, the rifle had no real collector's value when I bought it because it was not factory original even then and had not been for a long time. It is generally accepted that alterations carried out by the original maker count as “factory original” for collecting purposes, but you need proof. The replacement barrel is a Winchester, but that is all we will ever know.

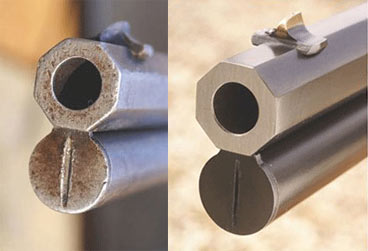

Mechanically, Turnbull found the rifle to be quite sound, but cosmetics were another thing entirely. The barrel was bad enough, with rust, pitting, and the odd dent and ding, but the receiver was a grey, splotchy mess. The magazine tube showed the usual signs of wear, and both the sharply curved rifle buttplate and steel forend cap were scratched, dinged and rusted. Every screw head in the rifle had, it seemed, been worked on with a hatchet. If any of the owners ever possessed a proper screwdriver, there was no evidence of it.

In a drawer I had an original Lyman receiver sight for an 1886, itself a valuable collector's item, and I sent it to Doug with a request that it be installed to match the rifle. The 1886 was going to be put back to work, as a hunting rifle, once it was all put to rights.

The old 1886 was a full-scale restoration project with the straightforward goal of making the rifle “as new.”

But I had a Winchester 94 of comparable vintage (1910, actually) that also needed attention. Here, the problem was quite different. The rifle was a 32 Special with a 26-inch octagonal barrel that had been well used but well looked after throughout its life.

From end to end, the 94 was aging gracefully as a century-old rifle should. The only problem was a large brown blemish on the left side of the receiver – a patch two inches square that reproached me every time I looked at it. At some point, the rifle had come in contact with something corrosive. Mercifully, its previous owners had not taken a wire wheel to it, so there was no real damage.

The challenge to Doug Turnbull's team of vintage-rifle experts: Refinish the receiver of the 94 but make it look at home, gently aged like the rest of the rifle.

The 94 and the 1886, although manufactured only 10 years apart, display a marked difference in the way Winchester made rifles.

“Receivers on all the early lever actions were case-hardened,” Doug said. “This was the process that hardened the exterior of the steel, and made it rust resistant, after it had been completely machined. The colors, beautiful though they were, were a by-product of an essential industrial process.”

A word of explanation: Frequently today we see reference to “case-coloring” – modern chemical processes which impart rippling blue and amber colors to steel, without changing the composition of the metal. Case-hardening, the original process, baked carbon into the skin of the steel, hardening it almost like glass, while leaving the steel beneath softer but tougher. Case-hardening was the final step, applied after the steel had been completely machined, polished and engraved.

As the quality of steel in firearms evolved, so did the final treatment applied.

“Around 1900, Winchester began using harder alloy steels for its receivers. They phased out case-hardening and began bluing the receivers instead, because the new steel was tougher and harder to begin with.” Turnbull said. “Your 1886 was made in 1900, so it was right on the cusp of that change, although it was case-hardened originally. The shell was hard as glass, as you would have found if you'd tried a file on it.

“Your 94, on the other hand, had been blued rather than case-hardened, so the challenge was to reblue it but make it appear the bluing was done many years ago.”

If much of this seems like black magic and alchemy, it is because it is. Gunmaking is an ancient craft, and many of the processes date back to a time of coal forges and leather aprons. Skills were passed from father to son. When a man was renowned for imparting a beautiful finish to a gunstock or case-hardening a frame to exquisite colors, the technique was jealously guarded within the family.

In many cases, alas, this led to arcane knowledge being lost. the making of damascus gun barrels, for example, is a lost art. No one today knows how to do it.

Today, many processes are standardized and a gun from one maker looks much like a gun from another. A century ago, however, each maker had his own techniques and the differences were highly prized.

Parker was famous for its case colors. In fact, Turnbull says, in terms of colors there were two types in America: Parker, and everyone else. Case-hardening is the most mysterious of all the gunmaking arts, since it involves baking steel in a mixture of charcoal and animal parts like bone or leather. It is the animal carbon that imparts the colors, and the secrets revolve around this type of bone, or that type of leather.

Doug Turnbull came by his interest in the old techniques through his father, who opened a small retail business in upstate New York in 1958. Doug was born three years later, and grew up in his father's shop, watching as he experimented with different techniques of metal finishing, and talking with customers and enthusiasts who came in with antique firearms in need of work.

Although he did not train formally as a gunsmith, Doug went into the business when he finished school, and took a special interest in restoration.

“My father had been experimenting with case-hardening and metal preparation,” Turnbull said, “And I took over that side of it. It turned into years of trial and error. Some of these processes are literally lost arts. There are no books about it. Very little was written down, but in the 1960s, a few of the old craftsmen were still alive and were eager to pass on what they knew, if anyone asked.

“My father learned from them, and I learned from him.”

Just like the old way, when you think about it.

Another aspect of authentic restoration is matching the level of original workmanship. Over the years, as manufacturing methods changed and different pressures – usually economic – were brought to bear, gunmakers reduced the attention they gave to certain details. This is easiest to see on a rifle like the Winchester 94, which was manufactured during the entire span of 20th century industrial history.

Loosely – and this applies to all firearms – there was the golden age of craftsmanship which lasted from the late 1800s until 1914, when the world went to war. When commercial production resumed after 1918, many of the practices learned (and bad habits acquired) during the war years were applied. Pearl Harbor was the next great watershed, and by 1950, the whole philosophy of mass-production gunmaking had changed.

Put a 1900-vintage Model 94 beside one made in 1912 and you'll see a slight difference; add one from 1921 and the difference is striking. And after 1945, it was all downhill.

Doug Turnbull and his specialists have studied this aspect of restoration and can return a rifle or handgun to the original level of workmanship. Amateur refinishers usually rush the polishing so they can get to the bluing, which is totally wrong.

“Time spent in preparation is all-important,” Turnbull said. “Take your 1886. We knew from the hardness that it had been case-hardened originally. It was right at the end of that era – the switch over to bluing the 1886 took place around serial number 120,000.

“We dismantled the rifle completely, cleaned it, annealed the receiver (to eliminate the hardness), polished it, re-cut the lettering and factory markings, then case-hardened it using the original Winchester process.”

It sounds simple, but it is painstaking indeed. Polishing requires extreme care, a light touch, and exquisite attention to detail. Pitting almost always looks worse than it is. A shotgun bore with pits like the craters of Mars can often be polished and not even go out of proof. The essential thing is never to remove more metal than is absolutely necessary.

A square, flat surface like a lever-action receiver requires special care in order to come out the other end looking square, flat, and even, with sharp corners. To the naked eye it looks factory original; only a sensitive caliper reveals the dimensional difference.

Proper metal polishing is an under-appreciated art. It was the key to the seductive smoothness of guns from the golden age. The parts were polished inside and out. Look at the internal bits of a Holland & Holland, made then or made now, and you will see every little bit polished to perfection. This gives smooth, effortless operation. As industrial processes deteriorated after 1914, polishing was steadily reduced.

“Proper polishing requires time, and time is money,” Doug Turnbull says. “If you can eliminate ten hours of polishing, that is a substantial reduction in costs. Internal parts can often be left unpolished without materially affecting the operation of the gun, at least in the short term, so they let them go.

“Over the years, less and less polishing was applied, and it shows in both the operation and the external finish on these guns.”

Turnbull's favorite example is the venerated Colt single-action revolver. “A Colt from before 1913 was given 35 to 45 hours of preparation to get the finish ready for bluing and case-hardening,” he says, “While one from later years was given only 25 to 30 hours.” Therefore, in restoring one, you want to restore only to the level of finish appropriate for that era. Turnbull said he could make a post-1918 Colt as good as a pre-1913 one, but then it wouldn't be authentic.”

No production Winchester was ever made to the level of finish of an H&H Royal, but even so the difference between an old and new 94 is readily apparent. An action that starts off slick gets slicker with use; one that starts off rough only gets rickety. The 1886 has a reputation as the smoothest lever gun Winchester ever made; part of that is the design, but part is the level of internal finish.

Bluing is an art in itself, and one that requires knowledge of both metallurgy and chemistry.

Like case-hardening, bluing served a number of purposes. Not only did it impart a surface finish that would reduce reflection, resist rust, or simply make the gun more attractive, but the method of bluing sometimes changed the qualities of the metal itself.

Old Winchesters require three different types of bluing to duplicate factory condition: nitre, carbona (or charcoal), and rust bluing. Each has its own use.

Nitre blue imparts that deep, iridescent, midnight blue that one sees on gun springs, screws, and the door of a lever-action loading gate. It requires glassy polishing and surgical cleanliness. It is used where temper and hardness are critical.

Carbona is a heat blue, used on small parts as well as the receiver of the rifle. It draws some of the hardness out of the metal, so one must be careful in its use, but it is easier than nitre and less labor-intensive than rust bluing. It imparts a deep, lustrous finish.

Rust bluing is used on barrels and magazine tubes, and has more of a matte appearance. It is applied by immersing the barrel in the solution, letting it rust, carding it off, re-dipping and re-carding ad infinitum until the desired shade and depth of blue has been achieved.

Since these processes look different from the start, they age differently, which is why old Winchester receivers age to grey, while the barrels go brownish. It is an attractive look that makers of new guns now spend time and money trying to reproduce.

A critical change for barrel bluing took place in the early 1900s during the switch from blackpowder to smokeless. Gunmakers needed harder, tougher steels to resist the greater pressures and intense heat of smokeless powder, and abrasion from jacketed bullets. For Winchester, the star cartridge of the dawning smokeless era was not the 30-30, as one might suppose, but the later 32 Special. It was introduced only after they had perfected the use of nickel-steel barrels, and my 32 wears a barrel that has imprinted on it “NICKEL STEEL BARREL – ESPECIALLY FOR SMOKELESS POWDER.” Nickel steel is stainless steel of an early type, and naturally resists rust, so it requires a different bluing process. This is one reason two barrels from the same general era might age differently.

After 1940, black oxide became the standard commercial bluing method. It is a water-based chemical blue that is easy and fast but cannot match the beauty of either rust or carbona bluing.

The barrel and magazine tube on the 1886 were rust blued and its loading gate nitre blued. The receiver on the Winchester 94 was carbona blued. The differences are deliciously apparent.

Finally, the stock on the 1886. The carving and scratching carried out by the previous owner, perhaps as long as a hundred years ago, rendered the stock not only ugly but unsalvageable. Bill Dowtin came through with a piece of Central Asian English walnut that looked as if Jove intended it for a vintage Winchester.

It had that prized natural red hue, whisperings of feather-crotch grain all the way to the toe of the stock, several layers of figure that glowed subtly through the oil finish, and straight, extremely strong grain through the wrist. The forend matched the color and rippled gently.

Turnbull put the blank on the pantograph with the original stock, and then turned the semi-finished product over to his stocker for fitting. The final touch was an authentic glossy Winchester finish.

At the center of any collector's concern is monetary value. Some years ago, Doug Turnbull told me about another restored Winchester 1886, as an example of how restoration can affect value.

The Winchester 1886 is a highly desirable collector's item. Only 159,994 were made, compared to more than a million 1892s and close to six million 94s. Turnbull took an 1886 that was worth, in its rather shabby, unrestored condition, about $3,000. Had it been in 98 percent original condition, it would have been worth as much as $20,000. Once restored to like-new condition, that $3,000 rifle sold at auction for $9,750. Not the equal of the collector's prize original, but still considerably more than it had been.

Steve Fjestad is editor of the Blue Book of Gun Values,the indispensable bible of gun dealers everywhere. Does he think collectors will ever accept restored firearms?

“The answer for most guns is ‘no,' except for factory reconditioned English shotguns and rifles by famous makers,” he said. “The English have never looked down on properly restored long arms, because they've sent their guns back to the factories for reconditioning for decades.”

(Also, it should be pointed out, it is very hard to define “factory original” when the vast majority of guns by companies like Holland & Holland were custom guns, made to the client's specifications. There simply are no standards by which to measure originality.)

I then asked Fjestad about restoring a rifle that has seen a lot of use, with most of the bluing gone, dings on the stock and no finish left. Is that a collector's item that should be preserved, or would it be better going to someone like Doug Turnbull to be restored?

“In that situation, you can't win either way,” Fjestad said, “And here's why: It's already not much of a collector's item because of its lower condition, unless it's a rare major-trademark model. And by the time you pay for a professional restoration, you may or may not get all your money back when selling.”

Fair enough. If money is the only consideration, then restoration may not be a rock-solid financial investment. After all, if you buy an 1886 for $3,000, have it restored for $4,000, and then sell it for $6500, you've lost money. But to a serious lover of fine firearms, there is far more to it than mere dollars.

Over the past decade or so, I have had several shotguns and rifles restored or (to use the British term) refurbished. In England, a “refurb” is completely respectable and its effect on value depends only on how well it is carried out. The economics became plain to me when it was explained that an unusable H. Holland 50-caliber muzzleloading double rifle could be returned to excellent shootable condition for $5,000 – after which I would have a rifle that might be worth $5,000.

At that point, you look at this chunk of scrap which is a potential piece of history and ask yourself what it is worth, to you, to salvage that piece of history for posterity, whether you personally profit by it or not. If you count as profit the feeling of having saved something valuable that otherwise would have been lost, and presenting it to lovers of fine guns to treasure forevermore, then you might become hooked as I have.

Among my pack of rescued puppies I have a 28-gauge James Erskine hammer gun from the 1880s that saw hard service in Africa; an 1890 E.M. Reilly boxlock that was owned by a Scottish gamekeeper, brought to the new world, and spent 30 years in the rafters of a henhouse; a Savage 1899 (1916), and an Ithaca trap gun (1921). All are in excellent working order, and each gets used.

Bob Lee pointed out that, with automobiles, restoration is almost always necessary just to get them to run “unless you want a pile of junk that just sits there.” For many rifles and shotguns, the same is true. Under the British proof system, to be used a gun must be in proof, and putting an old gun in proof often takes a complete refurb.

Looking at these fine old guns, all of them leaning casually against my bookshelf, and now with the Model 1886 proudly among them, I know that at some point I could get my investment back.

But there is something else. It is a truth universally acknowledged that more really fine guns survive through the years in really fine condition because when a buyer pays big money he tends to look after his investment, and his heirs do as well. A gun made as a tool gets treated like a tool.

The guns I have had restored are now firmly in the former category and a hundred years from now, with any luck, they will reside in the collection of someone who cares deeply about guns and workmanship. At that point, I sincerely doubt he will really care that they were restored or refurbished, unless it is to silently give thanks that people like Doug Turnbull existed.

For that matter, a hundred years from now, the imprimatur “Restored by Turnbull” on a Winchester 1886 might well carry as much cachet as the Winchester name itself.

This article is from Gun Digest 2008.

Learn More About Legendary Winchester

- 9 Greatest Winchester Rifles And Shotguns Ever Made

- Restored To Life: Winchester 1886

- Winchester Model 94: Receivers

- Winchester Model 12: The Perfect Pump-Action Shotgun

- Winchester Model 1897 Riot Gun

Next Step: Get your FREE Printable Target Pack

Enhance your shooting precision with our 62 MOA Targets, perfect for rifles and handguns. Crafted in collaboration with Storm Tactical for accuracy and versatility.

Subscribe to the Gun Digest email newsletter and get your downloadable target pack sent straight to your inbox. Stay updated with the latest firearms info in the industry.

![Best Concealed Carry Guns In 2025 [Field Tested] Wilson Combat EDC X9S 1](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Wilson-Combat-EDC-X9S-1-324x160.jpg)

![Best 9mm Carbine: Affordable PCCs [Tested] Ruger Carbine Shooting](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Ruger-Carbine-Shooting-100x70.jpg)

![Best AR-15: Top Options Available Today [Field Tested] Harrington and Richardson PSA XM177E2 feature](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Harrington-and-Richardson-PSA-XM177E2-feature-100x70.jpg)

I have a fairly nice 1886 Winchester in 38 56. I am considering having it rebored to 45 70. Do you do this work?

I have a fair \ly nice 1886 Winchester in 38 56. I am considering having it rebored to 45 70. Do you do this work?