Does buying the exact same gun twice make sense? It does if you're talking about the affordable and accurate Interarms Mark X in .375 H&H.

What Made The Interarms Mark X Mauser Stand Apart:

- Produced by Serbian Zastava Arms, which has a long history manufacturing Mausers.

- Swam against the surplus Mauser market with brand new rifles.

- Available in more than 8x57mm—calibers from .243 up to .458.

- Used a commercial Mauser action, sans striper-clip guide and thumb-clearance groove.

- Some came with adjustable triggers.

There I was, cruising a gun show many years ago. I spied a bolt-action rifle with a nice-looking stock on it sitting on one of the myriad tables. It was classic in design. Solid recoil pad. A Mauser action.

OK, I thought, picking it up. Oh, a .375 H&H.

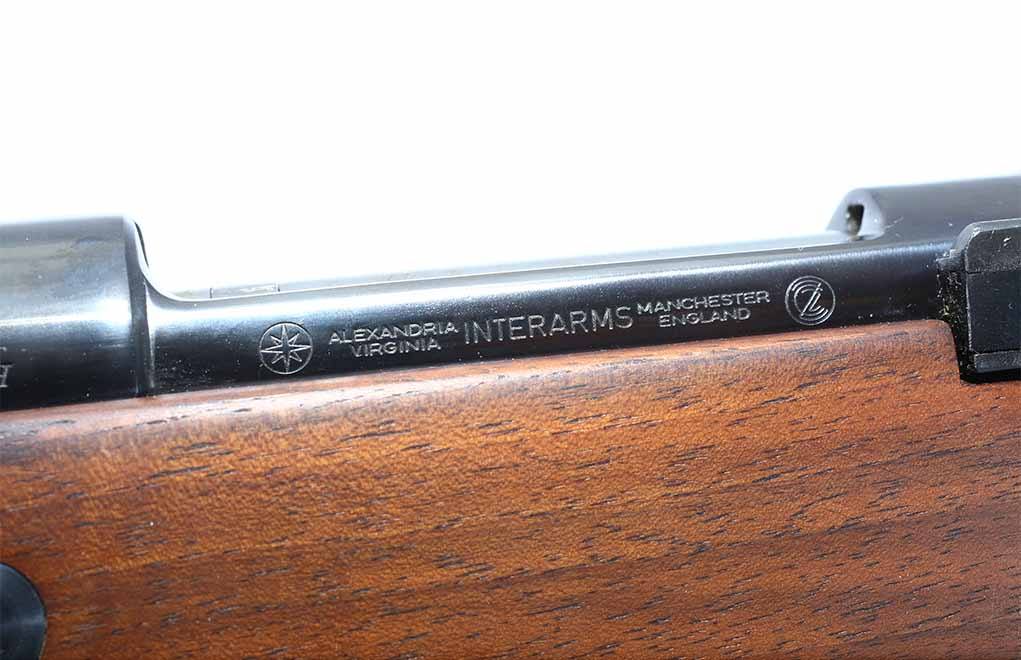

I worked the action (that tells you how long ago it was—they didn’t use zip ties on the actions back then), and it felt pretty smooth. I threw it to my shoulder, and the sights were dead on. This rifle fit me! I looked at the receiver, expecting to see a set of German or Argentine proofmarks. Instead, I saw “Interarms” and “Mauser Mark X.”

This was getting interesting, so I flipped the price tag over and blinked. This was a giveaway price! That made me suspicious, so I pulled the bolt out, looked down the bore to see if there was rust or pitting. Nope. Was the barrel straight? You betcha.

I turned to the guy behind the table.

“OK, what’s up?” He knew what I was asking.

“I want that rifle gone. I’ve sold it three times already, and the previous owners each brought it back.” Here, he switched to a whiney voice. “It kicked too hard, or the ammo was too expensive, or their wife nixed the idea of an African hunt.”

As I paused to think about it, he continued (in a normal voice). “At that price, I won’t buy it back. You buy it, it’s yours.”

So, I bought it.

Mauser Mark X Backstory

The Mauser Mark X was a line of rifles built on regular Mauser 1898 actions, manufactured in the Balkans by the company known as Zastava Arms. This manufacturer began making Mauser rifles between the wars, when it got licensed by FN to make a modernized 1898. In between World War I and World War II, many countries (some of them quite new), armed, and the arm-of-choice was usually the 1898 Mauser.

After World War II, Zastava cleaned up and resumed production of the Mauser, known by then as the M48. You’d think that war surplus could have supplied many buyers, but there was always a desire to equip one’s army with new rifles and not rebuilt ones of unknown provenance.

Enter into the picture a company known as Interarms. Sam Cummings, the owner, did a brisk business in buying up and shipping off surplus arms, excess to various countries’ needs. The Gun Control Act of 1968 (I know, that’s ancient history, but that’s where we are right now) put a real roadblock in the path of importing surplus, so Cummings went to Zastava and contracted for new rifles.

Instead of a surplus Mauser in 8×57, you could buy a new Mauser in .30-06, along with many other calibers. You could have had a Mauser Mark X in calibers from .243 up to .458 while Interarms was bringing them in.

There were a lot of other rifle makers using the Mauser action, either surplus or new, to provide American shooters with the bolt-action they desired.

Mine, the Mark X Alaskan Magnum, (aka Whitworth Express) in .375 H&H, is a standard-length action that has been opened a bit internally to accommodate the big cartridge. The .375 came to us by way of Holland & Holland (London) in 1912. The idea was simple: Provide a medium-bore rifle in the new, but well-established, smokeless powder—offering everything the big-bores with lead bullets could not. Because it used only jacketed bullets, the .375 was able to deliver rifle-level velocities with terrific penetration.

My rifle is also one of the ones marked ”Whitworth” and bears British proofs. All the Mark X Interarms rifles were made on “commercial” Mauser actions. That is, they lacked the stripped clip guide and the groove in the left sidewall for thumb clearance. They all came with scope base holes drilled and tapped on the receiver. The lack of a stripper clip guide and the scope mounts holes meant a gunsmith had a lot less work to do to make it a hunting rifle.

These rifles also came with a new, sleeker bolt shroud, and the safety on mine is on the right side of the action, connected directly to the trigger mechanism. The trigger mechanism is adjustable, but I’ve never felt the need to change it, because it came properly set (I have no way of knowing whether that was from Interarms or one of the previous owners).

The Alaskan Magnums came with cut checkering on the stock, not pressed, a recoil lug throughbolt, and it lacked the gloss finish and white-line spaces so in vogue back in the 1970s and 1980s.

More Rifle Articles:

- Weatherby’s Krieger Custom Rifle

- Aussie-Style Accuracy With The Lithgow LA102

- 5 Articles On The 6.5 Creedmoor You Must Read

- Best Precision Rimfire Rifles Guaranteed To Own The Bullseye

- AR-10 vs. AR-15: How Stoner’s Rifles Stack Up

Whitworth? Well, back in the 1970s, Yugoslavia was still a communist country. But, by having actions or barreled actions shipped to England and then stocked, fitted, regulated, proofed and shipped to America, the Yugoslavian origins could be overlooked. And, to be fair, a whole lot of importers were bringing in Mauser actions and rifles from FN, Yugoslavia … and who knows where else.

The .375 Case

The case of the .375 has a belt at the bottom. This is for headspacing, a concept not much in use in the United States for some time after 1912. It isn’t that it’s stronger; it allows the tapered case to be securely and consistently headspaced.

Why is the case tapered? In 1912, the British were still using cordite. This was a relatively quick-burning rifle powder that came in long strands. Think of a sheaf of uncooked spaghetti strands, standing on end in the case, and just long enough to not touch the base of the bullet.

The British arsenal loading procedure was to create the belted case but leave it in full diameter. The machines (or operators) dropped a measured amount of cordite strands into the case. Then, the case would be necked to create the shoulder and the bullet was seated. With the powders in use today, the cases are formed, necked and shaped. Powder is then dropped and the bullet is seated, but the shape remains.

That was the process there and then, and it required tapered cases. Consequently, the .375 H&H is tapered.

The end result here is a German design from 1898—licensed from a Belgian company in 1924, machined by a Yugoslavian manufacturer in the 1970s and imported soon after by an American entrepreneur—that is fed with ammunition manufactured here, in the United States, in the 21st century.

Thumper Recoil

Oh, and the recoil? It might be “moderate” by the standards of the end of the 19th century, but make no mistake: It thumps you. The Mauser Mark X was a relatively light rifle for the time, between 7½ and 8 pounds in the standard calibers. Mine? Eight pounds, 13 ounces, empty. Trust me: That is light in a .375 H&H. The heavy-bullet .375 H&H load has a bullet twice the weight of a standard .30-06 at nearly the same velocity. You’re getting anywhere from one and a half times to twice the recoil of a .30-06.

Even so, you get accuracy, penetration, reliability … and panache. As an acquaintance of mine is wont to say, “The advantage of overkill is that things stay killed.”

Now, I’m not sure I’d want to be hunting whitetail deer with a .375 H&H, but were I going after anything bigger, I know a solid hit with a .375 is going to get the job done. Right now.

Wait A Minute

The story on my .375 H&H? When I went home, I unwrapped the rifle, stepped up to the rack and shoved it into an empty spot. And then, I stopped, my hand still on the rifle. Right next to it in the rack was a … you guessed it: an Interarms Mauser Mark X Alaskan Magnum in .375 H&H—with the same classic stock. As I said, it’s a rifle that’s so nice, I bought it twice.

Over the course of a few months, I took both of them to the range on several range trips (I was a full-time gunsmith then, and range trips were at least weekly; during some seasons, they were several-times-a-week affairs) and determined which of the two was the better-shooting rifle.

It wasn’t easy. First, there is the recoil. I found that accurate benchrest work involved two groups from each rifle, maximum. Only later did I discover the trick of a standing support for test-firing magnums. If I shot any more than two groups each (and it took all day to do that), I wasn’t shooting my best. So, one box of ammo per trip, averaged over many trips, with several different loads.

One of these days … .

Second, they were both accurate, and the difference was small. I’d say that one was better than the other by a bunch less than an inch at 50 yards. Yes, 50 yards. I wasn’t going to invest in identical scopes to scope both of them for a fair comparison. Shooting them at different times would not have produced accurate results. And, with iron sights, 50 yards was as far as I was willing to walk many, many times to determine accuracy.

No, I’ve never been to Africa on a hunt. I’ve been there for an IPSC competition, with one near-event that might have resulted in “hunting” or at least an altercation. Had that happened, it would have been over and done with using a 1911, not a Mauser. I’ve visited Canada a bunch of times and Alaska several times. However, a .375 H&H wouldn’t have been appropriate on any of those trips (I’ve got to correct that).

So, it sits in the rack, patiently waiting. It’s sighted in and shoots all the loads I’ve ever tested in it to the point of aim. That part is a hallmark of the .375 and bolt-action rifles—one I can attest to.

All bullet weights shoot to the same point of impact in a given rifle out to useful distances. As a result, you can switch from the 300-grain FMJ buffalo penetrators to the 270-grain spitzer soft-points and not worry about changes in point of impact. The same rifle can be used on dangerous game and big plains game—all in one trip. If you have to have a flatter-shooting load for use out past 50, 75 or 100 yards, Buffalo Bore offers a 235-grain bullet: a TSX in the .375 H&H.

Right now, the cartridge is 107 years old. The bolt-action design is 121 years old. My rifle is probably 40-plus years old, and the ammunition I will have it loaded with will benefit from the latest bullet design and powders to be had.

Some things just don’t go out of style or lose their effectiveness. All hail the .375 Holland & Holland! As long as we’re hunting critters that can stomp, claw or bite us, there will be rifles in use chambered in .375 H&H.

Oh—if you want yours, start looking. They can still be had at reasonable prices. Who knows? Maybe yours will be the former stablemate of mine.

The article originally appeared in the June 2019 issue of Gun Digest the Magazine.

Next Step: Get your FREE Printable Target Pack

Enhance your shooting precision with our 62 MOA Targets, perfect for rifles and handguns. Crafted in collaboration with Storm Tactical for accuracy and versatility.

Subscribe to the Gun Digest email newsletter and get your downloadable target pack sent straight to your inbox. Stay updated with the latest firearms info in the industry.

![Best Concealed Carry Guns In 2025 [Field Tested] Wilson Combat EDC X9S 1](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Wilson-Combat-EDC-X9S-1-324x160.jpg)

![Best 9mm Carbine: Affordable PCCs [Tested] Ruger Carbine Shooting](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Ruger-Carbine-Shooting-100x70.jpg)

![Best AR-15: Top Options Available Today [Field Tested] Harrington and Richardson PSA XM177E2 feature](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Harrington-and-Richardson-PSA-XM177E2-feature-100x70.jpg)