I think the idea of sporterizing a military Mauser has been with me since I was in my early twenties. There is no doubt that it was the direct result of reading Jack O’Connor’s books and articles. He, of course, was the shooting editor of Outdoor Life magazine from 1937 until 1973, and, without doubt, was one of the most influential gun writers of that time. Like many others of my generation, I greatly admired O’Connor’s articles during the years when I was beginning to hunt, and could hardly wait for the next monthly issue of that magazine to arrive in the mail. Certainly, he had a lot to do with feeding my early passion for hunting and accelerating my love of fine sporting firearms, particularly the big-game rifles.

One type of rifle that he obviously admired was the custom sporting Mauser. For me, some of the pictures of his Mauser sporters were simply the stuff of a young rifleman’s dreams, and I hoped some day that I could have one of my own. However, I understood that O’Connor’s best Mausers were the products of the fine work of such master craftsmen as Alvin Linden, Al Biesen and W. A. Sukalle, and, as the years advanced, I knew that such custom work was far too costly for my budget. That left only one alternative: I would have to build my own.

Of course, I had no illusions of my work’s ever comparing to that of some great rifle-maker. After all, I’m no custom gunsmith – just a retired prosecutor who happens to love good rifles, hunting and competitive shooting. But, somehow, it seemed important to me to have a sporterized Mauser with the lines of the classic style of a bolt-actioned hunting rifle of the 1920s, ‘30s or ‘40s. And, if all went well, the fact that I would have built it myself would simply make it more special, to me at least.

Now, tinkering around at home with a surplus military rifle to make it more suitable for use as a sporting rifle – and to make it better fit the needs and taste of its civilian owner – is one of those hobbies that has occupied the time of many a rifleman/hunter. That pursuit probably achieved its greatest popularity in the years following World War II, when tons of U.S. and foreign military rifles were made available to the public. Shooting publications of the late 1940s, ’50s, and early 1960s commonly ran pages of advertisements from companies such as Klein’s, Winfield and Ye Old Hunter that promoted these low-cost, surplus rifles. Money was tight then for most average families, and the better military surplus rifles were seen as less-expensive alternatives for the big-game hunter. All that was needed was a little imagination and some time in the home workshop.

As a matter of fact, my first deer rifle was a Mark IV .303 British Short Model Lee Enfield (SMLE) that my dad bought for me from a discount store. The cost of the rifle was less than $20. Of course, it was my job to convert it into the sporting rifle I wanted.

I worked on that old .303 in our basement, usually at night and on weekends. I cut down the military stock, reshaped the forend, removed some unnecessary metal (such as the clip guide and military peep sight), shortened the barrel to 22 inches, and cold-blued the barrel and action. It was slow work, and painful, too, when a tool would slip at the wrong time. But, I learned a lot about files, rasps, hacksaws and other simple handtools during the process. Of course, I did not feel competent about doing some of the work. On those occasions, I would enlist the help of a local gunsmith, such as the one who added a Williams front-sight ramp and a Williams 5-D receiver sight. (By the way, that 5-D sight actually did cost only five dollars back then; the year was 1960.)

My conversion of that .303 British was very inexpensive. It was also a little crude-looking. But it worked. In November of 1960, I harvested my first deer with that rifle using a 215-gr. .303 British Winchester factory load. Some time later, I got tired of the look of the .303’s converted military stock and bought a semi-inletted, two-piece stock blank from Fajen. I took my time, carefully shaping and finishing the stock and even doing some follow-up metal work. The rifle now looks quite nice and still shoots well, either with 215-gr. jacketed bullets or with the heavier gas-check cast bullets such as Lyman’s No. 308284 or their No. 311299.

After all the time and sweat I had in that old .303 British, perhaps it should seem that the last thing I would want to do much later in life would be to start another such project. But, as I said earlier, O’Connor’s articles and photos had kindled that desire many years before, and now, after my retirement, I really wanted to try another military-to-sporter conversion, this time on a Mauser. And this time the conversion would be a more extensive one.

The basis of my conversion turned out to be a clean Yugoslav Mauser that I bought through my local gun dealer. The Yugo Mauser is a large-ring M98 variation with an intermediate-length action. When I got home, I disassembled it, and everything (including the stock and barrel) was discarded except for the action.

Before committing to a military-to-sporter conversion project, it is crucial to understand the rifle to be converted. There is probably no better source on the various Mausers, and how they work, than The Mauser Bolt Actions – A Shop Manual, by Jerry Kuhnhaussen (published and distributed by Heritage Gun Books). That book is filled with crucial information for the person who undertakes the home conversion of a military Mauser.

Of equal importance, the home gunsmith must understand his own limitations. Otherwise, the converted rifle may wind up in the trash, rather than in the hunting fields or on the target range. As an example, I wanted my converted rifle to have a streamlined bolt handle, rather than its unsightly military version. But, from the onset of this project, I knew I simply did not have the know-how, the experience, or the equipment necessary for that part of the conversion. Therefore, I farmed out that task to Bob Riggs, a nearby gunsmith who has had a lot of experience in such matters. As per my request, Bob cut off the old bolt handle and replaced it with a new handle which I had purchased from Brownells, the gunsmith supply house in Montezuma, Iowa. It was mounted to the Mauser’s bolt at the same angle as used by Winchester on its Model 70 actions.

As to the rifle’s new chambering, I gave some thought to one of O’Connor’s favorites, the 7mm Mauser (7X57) but finally decided on the 7mm/08 Remington instead. Handloaded to their full potential, these rounds are nearly identical ballistically. However, factory loads for the 7mm/08 Remington are loaded to much higher pressures (and velocities) than 7mm Mauser factory loads because the 7mm Mauser is chambered in many older, weaker actions. Further, although I handload almost all of my ammunition, there is always the chance of being on a hunting trip and, in a pinch, for one reason or another, having to rely on factory ammo. Thus, the nod went to the Remington round, which I consider completely suitable for medium big-game and for heavier varmints as well.

Of course, I needed a new barrel, and for that I contacted Douglas Barrels, Inc., of Charleston, West Virginia. That company has been supplying fine quality barrels — at reasonable prices — since just after World War II. And, besides, that business was located just a couple of hours’ drive from my home in Kentucky. A simple phone call to Douglas Barrels assured me that they could supply what I wanted. First, however, they wanted to test the hardness of my Mauser’s action to make sure it was suitable for the conversion I had in mind. I took the action to them, and it passed the test.

Just a few days later I had a new Douglas XX, “air-gauged” premium barrel in hand. I had opted for a medium-weight sporter barrel 24 inches in length. The barrel was delivered in the white, threaded for the Mauser action, and was chambered for the 7mm/08. The rate of twist was one turn in nine inches.

Since I would be barreling the action myself, the folks at Douglas had deliberately cut the 7mm/08 chamber slightly deeper than necessary to allow for proper headspacing. Following the instructions accompanying the barrel, I managed to headspace the barrel and mount it to my action using my small Smithy lathe, depth gauges, headspace gauges, a barrel vise and wrench, and, most importantly, a lot of patience. It turned out just fine.

After the rebarreling process was completed, the metal surfaces of the barrel, action, floorplate and new bolt handle were hand-polished down to a 400-grit finish using emery cloth. Although there was some pitting on the action, it was quite shallow, so the polishing was not quite as tedious as I had feared. I also thinned, contoured and polished the trigger guard, which added remarkably to the rifle’s overall appearance.

As for sights on my new rifle, I wanted iron sights only. I felt they would better suit the type of rifle that I had in mind. Besides, to me there has always been a certain added degree of satisfaction that comes when hunting with iron sights that is not present when the rifle is equipped with a scope. And I liked some of the early hunting pictures of Jack O’Connor and his wife, Eleanor, armed with scopeless rifles that were equipped with receiver aperture sights. Consequently, I made contact with a Texas dealer who specializes in old, out-of-production iron sights, and was able to locate exactly what I wanted: a Lyman 48M receiver sight, designed specifically for the Mauser 98 action. (The famous Lyman 48 receiver sight was in production continuously from 1911 until 1974. My 48M sight was the third edition of that sight, introduced in 1947.)

Using levels, a small machinist’s clamp and the drill press on my Smithy, I drilled and tapped the Mauser’s receiver for the old Lyman sight. That job was completed without a hitch, and, to me, the sight complements the look of the rifle.

The front sight that I chose to use was the N.E.C.G. “Masterpiece” Banded Front Ramp. This is a ramp sight that attaches to the barrel by means of a barrel band. It is sold in conjunction with several different interchangeable front sight inserts. The insert I chose was a post with a sloping, brass face, reminiscent of the old Redfield “sourdough” front sight.

I found an unfinished, semi-inletted stock blank for my 98 through Bob’s Custom Gun Shop of Polson, Montana. To ensure that the stock’s holes for the guard screws would properly align with my “intermediate” length Yugo action, I shipped the action to them, and they cut the blank using the Yugo action as a guide. Once the action and stock were returned to me, I found the stock’s wood to be a nicely-figured grade of dense, dark walnut. Also, per my request, the folks at Bob’s had fitted a steel grip cap and one of the checkered-steel Neider buttplates to the stock, saving me many hours of labor. But there was still a lot of work to be done on my part before the stock would be completely fitted and finished.

To ensure that the stock would be tightly fitted to the action, I finished inletting for the barrel and action using the old lamp-black method. Simply put, I “smoked” the barrel and action over a kerosene lamp. (Actually, my kerosene “lamp” was a small, glass baby-food jar with a metal lid; I punched a hole in the center of the lid and slid in a round wick. The jar was then filled with kerosene and the wick was lighted and adjusted to a higher-than-normal position to allow it to smoke. This is much smaller and handier around the workbench than a regular kerosene lamp.) The action and barrel were held over the lamp’s wick and, once sufficiently blackened, were then carefully placed in the stock, and tapped lightly with a rawhide hammer so that smudges would be left by the lamp black where the metal came into contact with the wood. The action and barrel would then be lifted from the stock, and a scraping tool was then used to remove the black marks that had been left on the wood. This process was repeated many dozens of times before the inletting was complete, but the result was an inletting job that was as perfect as I felt I could achieve.

I chose to “float” the barrel in the stock rather than have it bedded to contact the stock’s forend. Floated barrels have given the best accuracy in my target and hunting rifles and have proven to give less change in the point of impact of the bullet in differing atmospheric conditions. Consequently, when the inletting was finished, I removed some of the wood of the stock from the flat under the front receiver ring and from the recoil lug recess to a point in the barrel channel about 1-1/2 inches ahead of the action. This allowed room for the bedding compound; I used Brownells’ Acraglas Gel. After the Acraglas bedding process was completed, I then removed just enough wood in the remainder of the barrel channel so that a dollar bill could barely pass between the barrel and its channel in the stock. As a result, the only place the stock’s forend and the barrel made contact was the first one and one-half inches ahead of the receiver ring.

I wanted my rifle to have the look of some of the older American and European bolt-actioned sporting rifles, so I cut the forend of the stock to a shorter length than is commonly seen today. I did not intend to use a “shooting” sling on this rifle; rather, I wanted only a carrying sling. The front swivel for that sling would attach to a stud that would be part of a barrel band that would be mounted about three inches in front of the tip of the forend. I located such a barrel band swivel stud (manufactured by Gentry) in the Brownells’ catalog and ordered it.

When the remainder of the stock-shaping was accomplished, it was sanded to a smooth finish using 200-grit sandpaper and then #00 steel wool. The last stock work prior to applying the finish was to lightly moisten the stock with a damp cloth to raise the grain and sand it smooth again with the steel wool. This last process was repeated 4 or 5 times until the grain of the wood could no longer be raised.

Next, French Red stock filler was rubbed into the stock and allowed to dry overnight. It was rubbed off across the grain after drying completely. Once I was satisfied that the grain had been filled, the stock was ready for its finish. For that, I chose Birchwood Casey’s Tru-Oil. I applied the Tru-Oil using #00 steel wool. I dipped a small “tip” or point of the steel wool into a tiny amount of Tru-Oil and rubbed it into the stock using small, circular motions. Each such application would cover only about a three-inch section of the stock, and, as soon as each application with the steel wool was completed, and while the oil was still wet, the excess oil was rubbed off across the grain using a clean, soft, lint-free cotton cloth. At that point, I began applying Tru-Oil, in the same manner, on the next three-inch section of the stock. Once the entire stock had been covered in this way, the stock was set aside to dry for 24 hours. After that time, another coating was applied in the same manner.

I considered the stock’s finish to be completed after the application of about five coats of oil. The finish obtained by the method I have described is a deep sheen, and, to my eyes, is much more attractive than the glaringly shiny, spray-on, acrylic finishes seen on some commercial gunstocks today. A hand-rubbed oil finish not only has a nice appearance, it is reminiscent of the time when gunmakers took real pride in the quality of their products, rather than placing the emphasis on how quickly rifles could be turned out.

By the way, at the outset of this project, I fully intended to checker the stock myself. However, after much practice on many odd pieces of scrap walnut, I finally came to the conclusion that, like the replacement of the bolt handle—any checkering of the stock should best be left to a professional. It is still possible that I might have checkering added in the future. But, even without checkering, the stock is still very pleasing to me.

Next, all metal parts of the rifle – barrel, action, front sight ramp, front swivel stud, grip cap and buttplate – were blued. I chose to use Belgium Blue for this process, a product which I had used before and had liked. Belgium Blue is wiped on after the part to be blued has been heated in boiling water, so, all the home gunsmith needs in the way of special equipment is a tank large enough to hold the part to be blued and an adequate heating source. After each application of the bluing compound, the part is “carded” (rubbed down) with steel wool to remove the excess bluing solution from the surface of the metal. Once enough successive applications have been made, as per the instructions, a deep, durable, blue finish results.

With the bluing completed, I mounted both the front sight ramp and the front swivel stud to the barrel. Their barrel bands had been ordered with inside diameters slightly smaller than they would need to be, so as to permit a snug fit on the barrel. To bring them to the proper size, I fastened each in a padded vise and used 200-grit emery cloth (wrapped around a dowel rod) to slowly increase their inside diameters to the dimensions needed. Once this had been done, the inside of the barrel band of the swivel stud was given a light coat of Brownells’ Acraglas Gel epoxy and was tapped into place on the barrel. The Acraglas was used, of course, to prevent the stud from moving, and this is much easier than using solder to accomplish the same result. Any excess epoxy was immediately wiped from the barrel with an oily rag. Once the swivel stud was in place, I used the same method to mount the front sight ramp to the barrel.

At this point, my conversion was basically complete. Of course, conversions of military Mausers can be much more extensive than the one I have just described. For instance, I could have changed the trigger from the original two-stage military one to a crisper single-stage trigger. Many brands of replacement triggers are available, but I do not mind two-stage triggers in the least for the deliberate type of shooting that is generally encountered while hunting. Also, I could have opted to replace the military safety, which is a top-swing safety located at the back of the bolt. Such a safety simply cannot be manipulated as intended when the rifle has a telescopic sight mounted in the usual position. But, again, I had no plans of mounting a scope, and the military safety – a three-position safety – suits me just fine. Further, adding such replacement parts can also cost a lot of extra money, and, the person considering the conversion must decide if the advantage offered by the after-market part is really worth the added expense.

With the work of converting the rifle behind me, the shooting could begin. It was time to fire it for accuracy to determine whether any adjustments were needed. For a test load, I decided to try some Hornady 139-gr. spire-point boattail bullets. The load that I settled on for use with that bullet was 48 grains of H-414 powder with a CCI 250 primer. I seated the bullet just short of the rifling, and the overall length of the cartridge was then 2.85″. According to Hornady’s 7th Edition of its Handbook of Cartridge Reloading, this load is actually a little less than maximum for the 7mm/08 Remington cartridge.

Not only did that load prove to be nicely accurate, it was also fast. When chronographed from my 24-inch barrel, the load gave an average velocity reading of 2920 fps. No indications of excessive pressure were encountered. As far as accuracy was concerned, groups at 200 yards were very near minute-of-angle when fired from my bench. (It’s interesting to note that Jack O’Connor’s favorite factory load for his 7mm Mausers was the old Western 139-gr. open-point bullet at a velocity of 2850 fps. Regarding that load, O’Connor said, “I have never seen a hunter who used the 7mm with that load who did not like it.” My load develops slightly more velocity with the same weight bullet.)

Right-side, full-length view of author’s sporter conversion of his military Mauser. The lines given to the rifle are reminiscent of those of American and European bolt-actioned sporters of the early-to-mid 1900s. It is chambered for the 7mm/08 Remington cartridge.

Right-side, full-length view of author’s sporter conversion of his military Mauser. The lines given to the rifle are reminiscent of those of American and European bolt-actioned sporters of the early-to-mid 1900s. It is chambered for the 7mm/08 Remington cartridge.

My goal had been to create a rifle suitable for open-country hunting of medium game such as antelope, sheep, mule deer and caribou. I believed that the 7mm/08 cartridge was fully adequate to handle all such game as long as proper loads were used. Although there are many fine jacketed or monolithic hunting bullets being manufactured today, Hornady’s “Interlock” bullet design had proven reliable on medium-sized game for me in the past – with 270- and 30-caliber bullets – and I expected the same fine results with their .284″ (7mm) bullets. I believed that the load I had assembled would prove an excellent one for most of the hunting I would be doing with this rifle.

Frankly, I was quite surprised with the velocity of my load. The 2920 fps reading was more than I had hoped to achieve especially at less than maximum pressures. I know that in these days when many hunters seem to be focused on “magnum” cartridges of one kind or another, such ballistics may not seem very impressive. But, let’s take a minute to put things in perspective.

The .280 Remington and the .284 Winchester are both hunting cartridges with splendid reputations for effectiveness on game. Being 7mm cartridges, they, naturally, shoot the same bullets as the 7mm/08 Remington. Again, referring to Hornady’s 7th Edition Handbook of Cartridge Reloading, velocities with the same 139-grain Hornady bullet in the .284 Winchester and .280 Remington cartridges top out at 2900 and 3000 fps, respectively. Those velocities were taken in a 24-inch barrel with the .284 and a 22-inch barrel for the .280. Certainly, the velocity of 2920 fps in my 7mm/08 Mauser – with a less-than-maximum load, remember – is quite on a par with those two older, and widely acclaimed, hunting cartridges.

Another comparison that is interesting to make is with the famous and ubiquitous .270 Winchester. That cartridge has earned its place as one of the most outstanding medium-game hunting rounds ever produced. The same Hornady reloading manual lists a maximum velocity for their flat-base, 130-gr. Spire Point from a 24-inch-barreled .270 at 3100 fps. Although Hornady does not manufacture a 130-gr. 7mm bullet, Speer does, and in Speer’s Reloading Manual Number 12, top velocity for their flat-base 130-gr. spitzer from a 7mm/08 with a 24-inch barrel is an almost identical 3065 fps. Further, the ballistic coefficients of those two bullets are nearly identical. Thus, for practical hunting purposes, any difference in the performance of these two cartridges when loaded with the above bullets would have to be imagined, because I honestly don’t believe it could be perceived in the field.

Before leaving the comparison of the .270 and 7mm/08 cartridges, it must also be considered that while the .270’s top bullet weights are 150-160 grains, the 7mm/08 cartridge can be loaded with bullets as heavy as 175 grains. This would seem to give the 7mm/08 an advantage when deeper penetration on heavier game is desired. Such a load that shoots quite well in my rifle is the 175-gr. Hornady with a load of 45 grains of H-414 powder. Although I have not chronographed this load, it should be about 2600 fps, according to the Hornady manual.

In short, on paper, the fitness of the 7mm/08 as a hunting round for medium big game simply cannot be questioned. But, as always, the proof for a hunting cartridge is in the field.

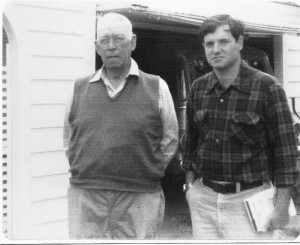

A couple of springs ago, after I finished sporterizing the Mauser, my wife, Linda, and I got to spend a few days on a ranch in Colorado where our friends, Ken and Susan Swick, and their two children, Brandon and Hannah, were working and living. Of course, I had taken the 7mm/08 with me; I had hopes that a coyote might show himself. During that visit, both Ken and Brandon fired some rounds from my newly-finished rifle, and each boosted my ego somewhat when they offered some favorable comments on its balance and appearance.

As it turned out, I didn’t see a single coyote during our visit, but Brandon (age 15) and I did spend a couple of hours one day thinning out a colony of rockchucks that were posing some problems on the ranch. (By the way, those rockchucks were fairly large, easily the size of the groundhogs we have back in Kentucky.) Most of my shots were from the standing and sitting positions, without a rest of any kind, and, of course, I was using just the rifle’s iron sights. I was delighted at the way the rifle handled in the field. Its comparatively mild recoil seemed out of place, however, considering the terrific power the 139-gr. Hornady bullets displayed on those rockchucks. That experience certainly made me look forward to using the rifle as it was intended on an open-country hunt for something bigger.

Well, when looking for “open country” and the game that inhabits it, one could not go wrong choosing an antelope hunt in Wyoming. I thought the plains-dwelling pronghorns would offer the perfect hunting challenge for my 7-08. So, in October of 2008, my converted Mauser and I – along with my friend and hunting buddy, Steve Geurin – wound up near Newcastle, Wyoming, for the beginning of antelope season.

On the day before the season was to open, we set up a tent camp on some public land administered by the Bureau of Land Management. After the tent was erected, we relaxed in a couple of lawn chairs and looked over the country around us. Basically, the view revealed a lot of sagebrush and many low-lying, prickly-pear cactus plants, along with a few small hills and some coulees that led toward a small valley with a nearly-dry creek running the length of it. On the far side of the creek was a lone, healthy-looking tree, the only one in sight.

Using our binoculars in the fading light, we could make out a little bunch of antelope milling around. They were on our side of the creek, nearly in line with the tree, and possibly a mile away. Hunting, it seemed, would be interesting here.

The following morning, we left the tent just after dawn and walked toward the area where we had seen the antelope the previous evening. The sun was not yet above the horizon when two doe antelope and one buck appeared just at the edge of a coulee directly in front of me. They ran away from me on a slight downhill grade in the general direction of the little creek in the valley. As they did so, I got in a sitting position and placed the brass post of my front sight on the buck, hoping he would stop within range. When the three antelope had gotten about 150 yards between us, they made a slight left turn and stopped in a rather open area in the sagebrush.

The buck was to the just to the right of the does. He had turned perfectly broadside to me; and, by that time, I had already taken the slack out of the trigger. After making sure that the sights were aligned properly, I put the last bit of pressure on the trigger and the rifle fired. The wide, gold-colored post of my front sight had been easy to see, even in the low light of the early dawn, and I knew instantly that the hold had been a good one. There was an audible “thunk” when the bullet struck. The buck ran in a tight circle and fell, only three or four seconds after being hit. The bullet had struck just above the heart and exited the chest on the far side, leaving a sizeable exit wound.

The buck was a young one, probably two or three years old, but I was a happy hunter. I have enough horns and antlers at home. After all, to me it is the meat that is most important, and a good shot on a smaller buck is better than a risky shot on a larger one. My homemade custom Mauser conversion – a sporting-rifle project that I had planned for over forty years, which finally made it to completion in my basement workshop – had performed its job perfectly. It had provided a quick, clean kill, and, in the process, had helped to put some fine meat on our family table.

In closing, I would like it to be noted that I must not be the only one who thinks my converted Mauser has the looks of a nice old sporter from the first part of the 1900’s. I can say this because of something that happened when I had finished the rifle and took it in to my local gun store to let the fellows look it over. As I handed the rifle to Jeff Furnish, the owner of the store, one of those who happened to be in the store that day, a rifle-lover by the name of Dave Robinson, was standing just a few feet away from Jeff. He looked at my rifle and said, “Hey, what is that—a Westley Richards?”

Well, if my rifle had been in Dave’s hands at the time he spoke, instead of being a few feet away, I’m sure he would have quickly noticed that my rifle fell far short of having the quality and workmanship of a Westley Richards-customized Mauser. But, nevertheless, when Dave asked that question, I’ve got to admit that I couldn’t have been prouder. With that one comment, he had recognized, at least from a distance, that there was a strong similarity between the rifle I had built and those classic bolt-actioned sporters of the first part of the 20th century.

And, after all, that was exactly the goal I had in mind for this project—a project that I had planned for over forty years.

This article appeared in the Gun Digest 2011, 65th edition annual book.

Next Step: Get your FREE Printable Target Pack

Enhance your shooting precision with our 62 MOA Targets, perfect for rifles and handguns. Crafted in collaboration with Storm Tactical for accuracy and versatility.

Subscribe to the Gun Digest email newsletter and get your downloadable target pack sent straight to your inbox. Stay updated with the latest firearms info in the industry.

![Best Concealed Carry Guns In 2025 [Field Tested] Wilson Combat EDC X9S 1](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Wilson-Combat-EDC-X9S-1-324x160.jpg)

![Best 9mm Carbine: Affordable PCCs [Tested] Ruger Carbine Shooting](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Ruger-Carbine-Shooting-100x70.jpg)

![Best AR-15: Top Options Available Today [Field Tested] Harrington and Richardson PSA XM177E2 feature](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Harrington-and-Richardson-PSA-XM177E2-feature-100x70.jpg)

Should you sporterize a Surplus Mauser?

No, decent sporting rifles are available in most calibers for almost the same price, sometimes even cheaper, than surplus military rifles. Why destroy a piece of history to have a cheap hunting rifle when you can go down to walmart and buy a Savage Arms Axis Rifle .30-06 for under $300?

The Yugoslav Mauser is “a piece of history” only insofar as that it is old. We are not talking a Purdy shotgun here.

Is it really possible that you read this article and came to the conclusion that it is about building a cheap hunting rifle? Really?