If you’re having trouble finding factory ammunition or brass for rifles chambered in obscure or obsolete cartridges, don’t fret: You can make your own.

Thinking straight about obsolete cartridges:

- With a good working knowledge of converting cartridges, a world of old guns in obscure calibers is opened.

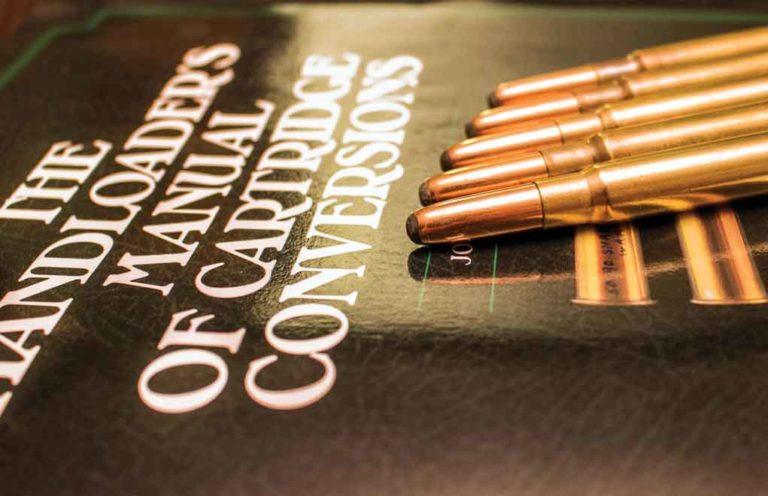

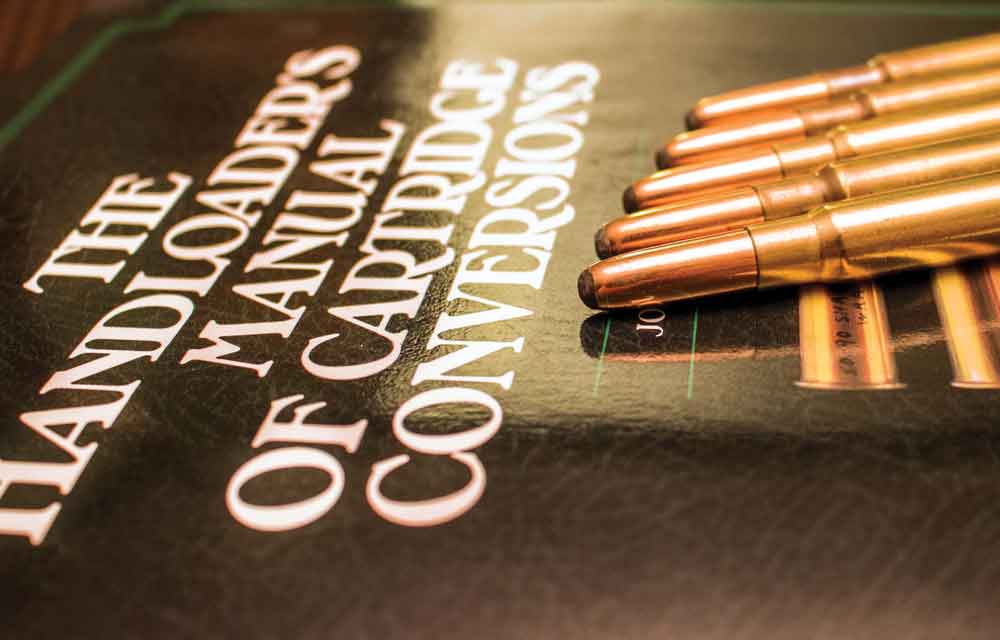

- An indispensable tool for the process is John J. Donnelly’s The Handloader’s Manual of Cartridge Conversions.

- The process can be as complex as removing a belt from a magnum cartridge.

- But it can be as simple as reducing a cartridge’s length and resizing its neck.

- Reloaders shouldn’t be shy, contact reloading companies — they are invaluable resources.

- On more complex, obscure projects you may need to invest in forming dies.

What do you do when you find that old rifle — sitting in the dusty corner of the gun shop, unloved, unwanted — that simply has your name written all over it, but it’s chambered for an obscure or obsolete cartridge? Why, you buy it of course! And if needs be, you make the ammunition yourself.

There have been several instances where this course of action has been warranted; there are some times when loaded ammunition — or even component ammunition — is simply not readily available.

The transformation of one cartridge case to another can be as simple or complex as your selection of tools will allow, but quite often making one cartridge from another will only require your reloading tools. A case trimmer can and will cut a cartridge down considerably, and a full-length resizing die can change the diameter of a case mouth, to a certain degree. But the first stop on your tour should be a particular book that warrants a place in every reloader’s library: John J. Donnelly’s The Handloader’s Manual of Cartridge Conversions.

It’s thick and largely technical, but it can and will be invaluable to those needing to create ammunition for a centerfire rifle when component brass isn’t available. My copy is more than 30 years old, and some of the reloading tools mentioned might be considered antiques these days, but the principles are still completely relevant. It makes an excellent full-service reference guide for the handloader, even if just in a learning capacity.

I’ve used it to create that which I could not purchase, and it’s worked out just fine. Now, while the book contains instructions on some of the more radical transformations, such as removing the belt from the Holland & Holland family of cases or reducing the diameter of a cartridge’s rim, I have yet to need to perform those operations; my own transformations have been less complicated, yet they filled the need in the same manner.

An Easy Example

My colleague and good friend Craig Boddington called me one day to inform me that he was having a problem with a rifle he had just acquired. Craig said the barrel was marked .30-338 Magnum, and while that is — in essence — the definition of the .308 Norma Magnum, the chamber wouldn’t handle the Norma factory ammunition.

So, I delved into the matter a bit more and found that after the .338 Winchester Magnum was released, yet before the .308 Norma Magnum was unveiled, wildcatters simply necked down the .338 case to hold .308-inch diameter bullets and maintain the same shoulder angle and datum line. There is a dimensional difference of a few thousandths between the two designs, explaining why Craig couldn’t close the bolt.

I made a call to Redding Reloading and found that — miraculously — they had a set of dies available for the wildcat. Because it maintained the same dimensions as both the .338 and 7mm Remington Magnum, either would be a suitable candidate for surgery. I decided it would be easier to neck up than to neck down and settled on new 7mm Rem. Mag. brass.

One run through the full-length resizing die — equipped with a tapered expander ball – and I was in business. Datum line was maintained, case length was just a few thousandths below maximum (a bit of length was lost in the stretching process) and the inside of the necks didn’t need to be turned. Loading for the rifle blindly, Craig reported that it gave him good velocities and 1 ¼ MOA accuracy (from a low-powered vintage scope), but most importantly, it was safe in the rifle with no pressure signs.

A More Involved Project

My own rifle was a bit of a different story, requiring some trimming and reworking to bring it to life. I have always wanted a .318 Westley Richards, yet finances dictated that the purchase of a genuine vintage rifle would see me sleeping on the couch.

Instead, I embarked on a custom rifle build, giving new life to a WWI Gew. 98 Mauser — re-barreling it with a Kreiger .318 WR barrel. The rifle came out just fine, with the appointments I wanted. One little issue: The only available factory ammunition is very expensive, approaching and in some instances exceeding 10 dollars per round. Being a handloader, I thumbed through the aforementioned Manual of Cartridge Conversions and confirmed my assumptions: .318 Westley Richards cases can be easily made from plentiful .30-06 Springfield brass.

Step No. 1 was to trim the .30-06 brass from 2.494 inches down to 2.370 inches, and for that I used a good, piloted trimmer. Once cut to proper length, I cleaned up the case mouth — which was now square and rough from trimming — giving it a good chamfer and deburring.

Step No. 2 was applying a liberal dose of Imperial Sizing Wax along the base of the case, and Imperial Dry Neck Lube at the case mouth; one pass through the resizing die resulted in perfectly formed .318 Westley Richards brass.

The case mouth has been expanded from .308 inch to .330 inch, and once cleaned up, they can be used without the need to fire-form. Now, the true case head dimension of the .318 Westley Richards is 0.468 inch vs. the .30-06’s 0.473 inch, so to be completely transformed, a rim turning might be in order, but my rifle began life as an 8×57 Mauser, which shares the 06 case head.

Therefore, the bolt face and cartridge case head are completely compatible. When I choose to use actual .318 Westley Brass — a rarity sometimes available from Bertram — the 0.008 inch in case head diameter won’t make a bit of difference.

When Forming Dies Are Needed

These two examples are relatively simple solutions to the need for brass that is either unavailable or ridiculously expensive. The more radical transformations might require the use of forming dies — which will work the brass up or down in small increments — and brass annealing. Cases like the 6.5 Remington Magnum — capable of being made from .350 Remington Magnum brass or, in extreme cases, from .300 H&H brass — should see the use of a forming die in order to radically change the diameter of the case mouth. The same could be said for creating .35 Whelen brass from .30-06 cases; though, I’ve seen it done in a single step, albeit with varying degrees of success.

The .475 Turnbull — that lever-action gem that Doug Turnbull designed for the 1886 Winchester — is based upon the .348 Winchester case, and it will definitely require forming dies. There are so many designs based upon the .30-06, .308 Winchester or the belted .375 H&H case that many different cartridges can be made from this trio alone. Some of the obscure rimmed cartridges will require a bit more creativity, but with the Cartridge Conversion book, a good handloader can get the job done.

If the change is extreme, annealing your cases will prevent premature cracking and splitting by keeping the brass soft and pliable; annealing will also help to keep any brass that must be fire-formed in working order for as long as possible. The annealing process is not extremely technical, but that’s best kept for another conversation …

Editor's Note: This article originally appeared in the April 2018 issue of Gun Digest the Magazine.

Next Step: Get your FREE Printable Target Pack

Enhance your shooting precision with our 62 MOA Targets, perfect for rifles and handguns. Crafted in collaboration with Storm Tactical for accuracy and versatility.

Subscribe to the Gun Digest email newsletter and get your downloadable target pack sent straight to your inbox. Stay updated with the latest firearms info in the industry.

![Best Concealed Carry Guns In 2025 [Field Tested] Wilson Combat EDC X9S 1](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Wilson-Combat-EDC-X9S-1-324x160.jpg)

![Best 9mm Carbine: Affordable PCCs [Tested] Ruger Carbine Shooting](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Ruger-Carbine-Shooting-100x70.jpg)

![Best AR-15: Top Options Available Today [Field Tested] Harrington and Richardson PSA XM177E2 feature](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Harrington-and-Richardson-PSA-XM177E2-feature-100x70.jpg)

i am looking to develop a load for 318 calibre with 185grn bullets with vit165 powder in an old but very desirable Kriegof drilling with tapered cases can you help

best regards

Pete