What’s fact — and what’s fiction — when it comes to some commonly held shooting and hunting beliefs? You might be surprised.

Straight shooting on these common shooting misconceptions:

- Long barrels are more accurate than short barrels

- A bullet rises as it leaves the muzzle

- ‘Enough gun’ means dropping animals immediately

- Mystical ballistics really do exist

- Handloads are more accurate than factory loads

- There are magnums … and there are magnums

As in any pastime, there are myths and half-truths that seem to have a life of their own, and the world of hunting and shooting probably has more than its share. Because internal and external ballistics can be so … well, intimidating to those who are simply hunters and not technically oriented, it’s understandable. Then there are terminal ballistics and cartridge/rifle performance, which can be quite subjective.

As a boy hanging around the little sporting goods store my buddy’s dad owned on 131st Street in Cleveland, we overheard all kinds of stories that, as impressionable pre-teens, we took as gospel. After all, some of the men who hung around the store had big game experience in Pennsylvania, West Virginia — even exotic places like Wyoming and Colorado, so they had to know what they were talking about!

Shooting Myth No. 1: Long barrels are more accurate than short barrels

Actually, the reverse is more often the case. Short barrels are stiffer, and, thus, the amplitude of vibrations — or barrel flex — is less. Benchrest rifles sport short, thick barrels. It’s true, however, that where iron sights are concerned, a long-barreled gun can be aimed more accurately because the sight radius (distance between the front and rear sight) is longer and the margin of aiming error is less.

That’s why accurately shooting a handgun with a sight radius of just a few inches is so much more difficult than shooting a long gun. Conversely, using an aperture or “peep” sight further increases the sight radius of a rifle, so it provides the most precise non-optic aiming system. Of course, the use of a riflescope negates barrel length and sight radius having anything to do with aiming accuracy.

Shooting Myth No. 2: A bullet rises as it leaves the muzzle

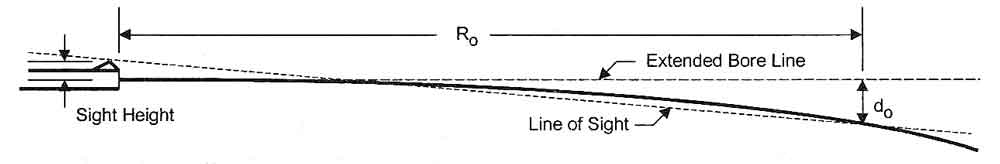

This is a myth to be sure, but there are a couple of caveats. For one, though a bullet begins to fall the moment it exits the muzzle, it does “rise” in relation to the line of sight (as opposed to the bore line, which is an imaginary line down the center of the bore out to infinity).

Whether utilizing iron sights or a riflescope, the line of sight — which is also a straight line out to infinity — starts out above the bore line, so if the two are to merge (zero) at any distance downrange, the sights (iron or optic) have to be angled downward to intersect the bullet’s trajectory. Normally, this first occurs out at 20-30 yards if one is zeroing in a typical centerfire rifle at normal distances. This is where “the bullet rises” comes from because beyond that first intersection the bullet is now traveling above the line of sight. As the bullet continues falling beyond that first intersection point, the two converge again at the desired sighting-in distance — your zero.

As for the other caveat, a bullet can, in fact, rise very slightly after exiting the muzzle. This seeming contradiction of Newton’s Law can occur if, at the moment of departure, the barrel is flexed so that its attitude sends the bullet out on a line slightly higher than the bore line. The longer and/or thinner the barrel, the greater the divergence can be, but it’s so miniscule as to be purely academic. It all makes sense if you just imagine giving a violent up-and-down shake to a garden hose and watch how it undulates. That’s what a gun barrel does as a bullet accelerates down the bore. It’s also why, when zeroing in or testing loads on a 100-yard target, a load pushing a heavier bullet can impact higher than a lighter one.

Shooting Myth No. 3: ‘Enough gun’ means dropping animals immediately

More a belief than a myth, it’s held primarily by “low information” hunters — to use a recently coined term for describing voters. Far too many hunters believe that if an animal doesn’t virtually drop in its tracks, “more gun” is needed. Such determinations are often the result of ego, especially if the animal is wounded and not recovered. “I can’t understand it; it was a perfect shot.”

Sure it was.

The truth of the matter is that the typical hunter today is over-gunned, and it’s especially true of whitetail deer hunters who comprise the vast majority of our ranks. If it were possible to shoot 10 identical animals under identical circumstances using the same cartridge and load, there would be 10 different reactions. With all being hit with a perfect heart/lung shot, some would drop where they stood, others would run anywhere from a few to a hundred yards or more.

The fact is, most hunters armed with 7mm and .300 magnums would be better served — and better shots — using a .260 Rem. or 7mm-08. Either is enough gun for all but the biggest bears and long-range elk hunting. And the .270 and .280 even more so.

Shooting Myth No. 4: Mystical ballistics really do exist

Back in the ’50s and early ’60s, the Weatherby Magnum rifle was more or less the Holy Grail for aspiring gun weenies like me, and apocryphal tales of Weatherby Magnum cartridges were quite common. Most often heard was that you could hit a critter in the foot with a Weatherby, particularly the .257, and it would drop on the spot as a result of “hydrostatic shock.” You don’t hear that one too much these days because we have so many cartridges that match or exceed Weatherby ballistics — and far too much empirical evidence to the contrary.

Shooting Myth No. 5: Handloads are more accurate than factory loads

Twenty-five years ago that was a fairly safe, though not certain, wager — assuming hunting rather than match bullets, and a modicum of handload development. Today, with premium loadings put together with superior components using more stringent quality control standards, it’s often difficult to match, let alone exceed, the performance of a premium factory load with a roll-your-own.

Ultimately, the handload will always win because the customization possible in developing a load for a specific rifle can’t be duplicated in factory ammo, but the amount of load development and range time required might not be worth what might be only a minimal difference.

Shooting Myth No. 6: There are magnums … and there are magnums

There are too many examples that defy accepted lexicon to list all of them here, but here are a few magnums that aren’t, and some non-magnums that are:

The .256 Win. Magnum, now obsolete, was a pipsqueak of a rifle cartridge based on a necked-down .357 Magnum pistol round, and the .25-06 Rem. is a magnum-class cartridge without the belt and title. Both are .25-caliber cartridges, but the .256 can’t carry the .25-06’s water.

The 6.5 Rem. Magnum, which was rolled out in 1965, had the moniker and the belt, but it couldn’t match the ballistics of the existing .264 Win. Mag. Both carried the magnum designation, but one was and the other wasn’t.

The .220 Swift was introduced in 1935 and — despite lacking the official magnum designation — has been king of the .22 centerfires ever since, tremendously outperforming the .222 Rem. Magnum introduced in 1958.

It wasn’t all that long ago that if a cartridge didn’t have a belt, a lot of folks figured that it couldn’t be a magnum. Today, virtually every magnum-class rifle cartridge that has been introduced these past 20 years or so are sans belt. Go figure.

Editor's Note: This article originally appeared in the March 2018 issue of Gun Digest the Magazine.

Next Step: Get your FREE Printable Target Pack

Enhance your shooting precision with our 62 MOA Targets, perfect for rifles and handguns. Crafted in collaboration with Storm Tactical for accuracy and versatility.

Subscribe to the Gun Digest email newsletter and get your downloadable target pack sent straight to your inbox. Stay updated with the latest firearms info in the industry.

![Best Concealed Carry Guns In 2025 [Field Tested] Wilson Combat EDC X9S 1](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Wilson-Combat-EDC-X9S-1-324x160.jpg)

![Best 9mm Carbine: Affordable PCCs [Tested] Ruger Carbine Shooting](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Ruger-Carbine-Shooting-100x70.jpg)

![Best AR-15: Top Options Available Today [Field Tested] Harrington and Richardson PSA XM177E2 feature](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Harrington-and-Richardson-PSA-XM177E2-feature-100x70.jpg)