Mils and MOA are both useful angular units of measurements, but is one better than the other?

The basics on MOA and Mils:

- Mils and MOA are angular mesurements.

- MOA is equal to 1.047 inches at 100 yards.

- Mil is equal to 3.6 inches at 100 yards.

- MOA is converted to Mils by dividing it by 3.43.

- Mils is converted to MOA by multiplying by 3.43.

This debate between milliradians (mils) and (minute of angle) MOA is never going to end, but we should at least agree on the facts right out of the gate. Every day we see the uninformed arguments about how one angular unit of measurement is better than the other. The truth of the matter is, one is not better — they’re simply different ways of breaking down the same exact thing.

Personally, outside of disciplines like benchrest shooting and F Class, I think minutes of angle should be retired. We have bastardized the unit to the point that people have no idea that a true MOA is not equal to 1 inch at 100 yards or 10 inches at 1000 — but 1.047 inches and 10.47 inches, respectively. If you round this angle, you create errors that exaggerate at longer distances.

Today, we shoot a lot farther than we have in decades past, and a 5 percent error compounding at an extended range will cause a miss. In fact, this is one of the main reason your ballistic software does not work: You default to MOA when, in reality, your scope adjusts in “inches per hundred yards” (IPHY).

Shooter MOA or IPHY is not a true MOA, and yes it does matter when companies mix them. Having someone question how IPHY is different when they don’t understand that we don’t use 1 MOA — or even 10 MOA — to hit a 1,000-yard target is frustrating to explain. If we consider a .308 Win. as a ballistic point of reference, we’re looking at almost 17 inches of variation between the two units of adjustment.

The Mil Advantage

We can quickly point to the adoption of mils here to demonstrate the ease of use, but then the Americans reading this will argue how they think in inches and yards, as if mils only work with the metric system. A Milliradian is an angle that subtends an arc whose radius is 1/1000th from the center. In other words: 1 yard at 1,000 yards.

So, 3,600 inches equals 100 yards, and 1/1000 of that is 3.6 inches. And when adjusting in 0.1 mils, we moved the bullet 0.36 inches per click at 100 yards. See what we did there? We simply moved the decimal point.

Some people believe an MOA is a finer unit of adjustment, but that’s failing to note that 0.3 mils is 1.08 inches at 100 yards. Contrary to popular belief, you can get a mil-based scope that moves the reticle 0.18 Inches per click. Mil-based scopes usually adjust in 0.1-mil increments; however, they do make scopes that adjust in .05 mils.

More Long-Range Shooting Resources:

- Exterior Ballistics Explained

- Ballistics Basics: Initial Bullet Speed

- Which Focal Plane Is Right For You?

- Holding Or Dialing For Drop And Windage?

- Mils vs. MOA: Which Is The Best Long-Range Language?

Mils are much easier to master than you might realize. Coming from the USMC Scout Sniper Program, our original M40A1 with the Unertl Marine Sniper Scope used a BDC Turret. The main turret was in yards, and the fine-tune lever was in MOA. Our dope was based on the range we were shooting more so than the MOA value.

In my case, my 500-yard dope back in the day was 5 minus 1. That meant to dial 500 yards on the scope, I turned the main turret to 5, and the lever to minus 1. The reticle was mil-based, and the lever was plus or minus 3 MOA. Today, the USMC is using mils.

While milliradians were added to the metric system many years ago, it was never designed to be a metric-only unit and works outside the metric system because it’s an angle-based unit of measure. Every angle has a linear distance between it, but you should be ignoring this fact and using the angle vs. picking a linear value to adjust your correction. For example, if I’m shooting 873 yards away, saying the bullet struck 6 inches off the target is neither honest nor accurate. You’re guessing. In your mind, it looked 6 inches away, but what if it was 9 inches? Using the linear value is more work, so why not just adjust the angle?

Minutes of angle started out like that too, but — unfortunately — companies took shortcuts and ruined it for everyone. It was easier to manufacturer to 1 inch vs. adding in the 0.047 inch. “Long range,” back in the day, was considered to be distances of 400 to 800 yards. Read any old-school book on ballistics, and it rarely goes past those ranges in their examples. Today, we’re shooting well beyond 1,000 yards, so that extra 0.047 inch matters more than ever, and you have to take it into account.

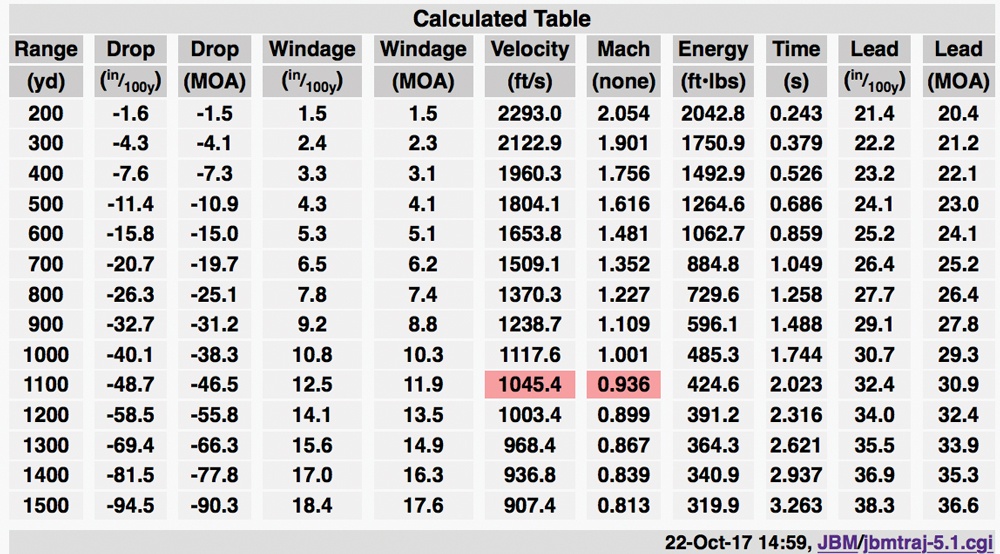

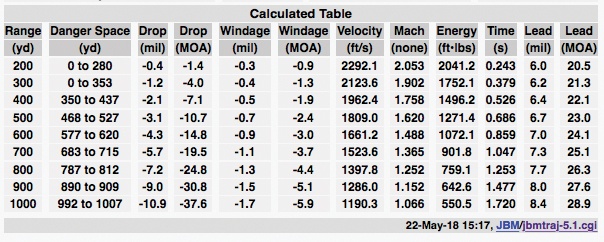

Defaulting your shooting program to MOA when you’re actually using IPHY is a significant point of error. As a reference, JBMballistics.com is a great place to demonstrate this because you can include both MOA and IPHY in the output. The same amount of adjustment is accomplished with two different values. Mix these numbers, and the result is a miss: Did you dial 40.1 or 38.3 MOA?

I highly recommend you map and calibrate your MOA scope to confirm its actual value. It works both ways, but not every MOA-based scope is TMOA — some are SMOA — and the compounding error is a lot bigger than 0.47 inches.

Again, neither mils nor MOA is more accurate than the other. I can hit the center of any target using either unit of adjustment. You simply need to truly understand the system you choose to employ.

So, Which Is Right For Me?

This is the ultimate question, and it should not be up to someone else to answer it for you. Communication is your number one consideration: What are your friends and fellow competitors shooting? You want to be able to communicate and understand what a fellow competitor is talking about when he walks off the line.

You can convert using 3.43, by multiplying or dividing the competing unit of adjustment against the other. That will give you a direct conversion:

12 MOA / 3.43 = 3.5 Mils

4.2 Mils x 3.43 = 14.4 MOA

Next, you have your reticle choices. You will find more versatile options when it comes to mil-based scopes vs. one referenced in MOA. However, that’s changing a small amount as manufacturers adapt. But a reticle with 1 MOA hash marks is not as fine as a scope with 0.2-mil lines in it. You now have to break up an already small 1 MOA into quarters. The mil-based scope is already breaking up the milliradian for you.

Pick the reticle based on your initial impression as well as your use. You don’t need a Christmas tree reticle to shoot F Class, and you don’t want to use a floating-dot benchrest scope for tactical-style competition. Put your intended use into the proper context.

There are a lot of articles about the nuts and bolts of mils and MOA. You can dig deep, or you can focus on understanding that we’re using the angle and there is no need to convert to a linear distance. A mil is a mil, and an MOA is an MOA (unless it’s not because you didn’t check). Today, I don’t even teach 1 inch at 100 yards, 2 inches at 200 yards, or 5 inches at 500 yards. It’s an unnecessary step and confusing to a lot of people. Not to mention, it’s not right: That is IPHY, not MOA — remember?

We also match our scope reticle to our turret adjustment, so at the end of the day, “what you see is what you get.” It matches what we see in the reticle, so we can dial the correction on the turret. This helps remove the need to think about adjustments … you just read what your optics are telling you.

If you’ve not made the change to mils, I recommend that you consider it. With a slight learning curve, you’ll find it’s much more intuitive than an MOA-based system. You don’t have to be a resident of Germany to understand it, and you don’t have to use it with meters. All my data is in yards, as mils directly translates to whatever range measure you use.

If the impact is off in any direction, you measure with the reticle and then translate that reading directly to the turrets: 1 mil is always 1 mil, and 1 MOA in any direction is a 1 MOA correction on the turret. Learn to be multi-lingual and speak in both mils and MOA. After that, the choice is yours as to which unit best suits your needs.

Editor's Note: This article originally appeared in the July 2018 issue of Gun Digest the Magazine.

Next Step: Get your FREE Printable Target Pack

Enhance your shooting precision with our 62 MOA Targets, perfect for rifles and handguns. Crafted in collaboration with Storm Tactical for accuracy and versatility.

Subscribe to the Gun Digest email newsletter and get your downloadable target pack sent straight to your inbox. Stay updated with the latest firearms info in the industry.

![Best Concealed Carry Guns In 2025 [Field Tested] Wilson Combat EDC X9S 1](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Wilson-Combat-EDC-X9S-1-324x160.jpg)

![Best 9mm Carbine: Affordable PCCs [Tested] Ruger Carbine Shooting](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Ruger-Carbine-Shooting-100x70.jpg)

![Best AR-15: Top Options Available Today [Field Tested] Harrington and Richardson PSA XM177E2 feature](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Harrington-and-Richardson-PSA-XM177E2-feature-100x70.jpg)

So, while you’re trying to praise MIL so much:

At 300 yards

1 MOA = 3.15″

1 MIL= 10.8″

1 click for a .1 mil adjusting scope, equals 1.08″ 1 click for a 1/4 MOA scope = .78″

Weird. It’s…almost as if MOA scopes allow for finer adjustments. And when shooting precisely…I wonder, wouldn’t you want finer adjustment? Should we take it out to 1,000, and see how much WORSE it gets for MIL?

1 mil is 3.6 inches not .36

Good catch.

Thank you for a very interesting and informative article. Double-check bullet point #3 in the intro: “Mil is equal to .36 inches at 100 yards.” Do you mean 0.1 Mil is equal to .36 inches at 100 yards, or, Mil is equal to 3.6 inches at 100 yards? Mils are so simple: one mil subtends 1/1000 of the distance between the scope and the target. I’m a big fan of the concept!

Good catch.

Really its an ultimate question which one is best fit for me? MIL or MOA. Most of the time I prefer MOA because its easy to set white Im hunt in a long distance like 400 to 500 yards. Its really easy to set MOA for someone who clearly understands how to set minute of angle (MOA). MIL a bit complicated for me. So always I go with MOA.

btw I got some clear understanding about MIL from this article. Thanks for you explanation.

This is a great article. I’ve really been studying over what type of scope to go with Mil’s or MOA. I’m more familiar with MOA but Mil’s is so easy to use and seems much more useful for the type of shooting I do. This has really helped with my decision.