After the war, both Colt and Smith & Wesson resumed production of commercial-grade guns for the police and civilian market. As it had been before 1941, the O.P. proved a bigger seller – but the situation was about to change.

During the war years, Colt had concentrated on building 1911 pistols and other weaponry, letting their revolver line languish. S&W, on the other hand, had upgraded their manufacturing processes and had a large pool of trained workers. With the war’s end, Colt was stuck with outdated equipment and a shortage of skilled labor.

Additionally, Colt revolvers required more hand-fitting and detail work, which significantly increased their price compared to the competition. Lastly, while S&W embarked on a long-term R&D program to improve their revolvers, Colt’s management seemed content to live off their reputation and did little to improve equipment, efficiency, their labor force and, most significantly, the product. This recipe for disaster led to S&W’s capturing an ever-increasing share of the police and military market.

1948 saw the venerable M&P’s designation changed to the Model 10. Seven years later, S&W introduced a K-frame revolver chambered for the .357 Magnum cartridge: the Model 19 Combat Magnum. Police agencies seeking more powerful weapons bought them as fast as they could be produced. Colt attempted to play catchup by re-chambering the O.P. for the .357 cartridge and adding a heavy barrel, adjustable sights and larger grips. Known as the Colt 357 Magnum, sales were disappointing.

The popularity of S&W K-frame revolvers, however, continued to grow as such prestigious agencies as the New York State Police, FBI and Royal Canadian Mounted Police adopted them. S&W also sold large numbers of them to police and military forces in Europe, Latin America and Asia.

.357 Magnum Model 13 revolver. This model, with a 3″ barrel, was adopted by the FBI. (Courtesy of Michael Jon Littman)

The handwriting was now on the wall. Colt went through a series of new owners, none of whom seemed interested in innovation; the product line remained stagnant; and quality control took a hit while a series of labor disputes adversely affected production and the company’s reputation.

As is evident from a 1976 survey taken by the New York State Criminal Justice Services, by that time, the police market was S&W’s private preserve The sidearms used by the 45 state police agencies responding to the survey broke down as follows:

In an attempt to stay solvent, Colt began dropping models and 1969 found the O.P. missing from the catalog. The name was briefly revived with the Mark III Official Police revolver, but sales were so disappointing that production ceased after only three years. Many shooters and collectors found it disturbing that Colt’s product line, reputation and popularity had sunk to such low levels.

The S&W Model 10 continued to be the firm’s bread and butter product, although with the advent of the troublesome – and more violent – 1970s, .357 K-frame revolvers soon became their most popular law enforcement product. Beginning in the late 1980s, the 9mm (and later .40-caliber) semi-auto pistol became the police sidearm of choice, and today it is rare to see an American police officer with a holstered revolver at his side.

Opinions regarding this change of equipment are varied, with both sides making many good points in favor of their preferred weapon but such discussions – which always threaten to become heated – is beyond the scope of this article.

Which Is the Better-Shooting Revolver?

You knew we were going to get around to burning gunpowder sooner or later, didn’t you? Accordingly I obtained samples of each revolver: my brother Vincent provided a very nice M&P made around 1940 while my fellow collector of oddities, John Rasalov, was able to supply an O.P. Despite its being of 1930 vintage, the latter was in very good condition and as mechanically sound as the day it left the factory.

First, several observations as to each revolver’s strong and weak points: I found the S&W to be the better balanced of the two, making it a more naturally pointing revolver.

Double-action trigger pulls are a subjective matter and while some prefer the way the Colt’s stroke has a noticeable stage just before it breaks, I prefer the lighter, stage-free pull of the M&P.

|

The O.P. was graced with a superior set of sights: a wide, square notch at the rear and the blade of ample proportions up front. While having the same style of sights, the Smith’s were smaller and harder to align quickly. In addition, the tip of M&P’s hammer spur actually obscured the rear notch until the hammer was slightly cocked. For the life of me I cannot fathom this, and wish someone could explain the reason for it.

When it comes to grips it was a tie. Both were horrible! I do not understand why it took the firearms industry several centuries to figure out that the odds of hitting the target would be greatly improved by a set of hand-filling, ergonomically-correct grips?

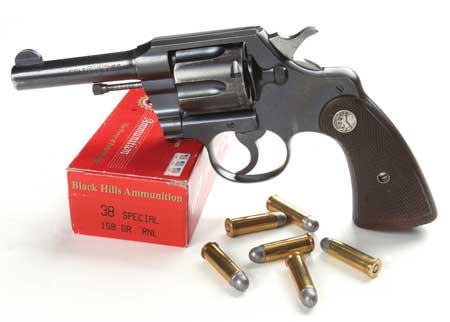

In keeping with the proper historical spirit I decided to limit me test firing to the type of ammunition that was most widely used during the era during in which this pair or revolvers had seen service. Black Hills Ammunition kindly supplied a quantity of .38 Special cartridges loaded with the traditional 158-gr. LRN bullets.

While I served as cameraman, my brother Vincent fired a series of six-shot groups with each revolver from a rest at a distance of 15 yards. As can be seen in the photos, both shot to point of aim and produced some very nice six-shot groups. I then set up a pair of USPSA targets at seven yards, and Vince ran two dozen rounds through each revolver, firing them both one-handed and supported.

What can we deduce from this expenditure of ammunition? Inasmuch as my brother Vince did all the shooting, I will quote him: “I can make several observations,” he says. “First of all, both revolvers proved capable of excellent accuracy, whether fired from a rest or offhand. And while the Colt’s sights were of a more practical design, I shot slightly better with the S&W. Whether or not this was due to the fact that I have much more experience with S&W revolvers, I can’t really say. The grips on both revolvers were poorly designed and I believe something as simple as the addition of a grip adapter would improve handling to a significant degree. The Tyler-T Grip Adapter was first marketed in the 1930s and I can understand why! As regards recoil control, with its greater weight, I found I could shoot the O.P. faster but, considering the rather sedate ammunition we used, the difference was not all that great.”

Vince summed it all up by saying, “I have long been a fan of the fixed-sight, double-action revolver and the performance of this pair only serves to buttress my long-held belief that they are one of the most practical type of handguns ever invented. I contend that for over a century they were proved capable of performing any law enforcement task they were called upon to perform and – despite the present popularity of the semi-auto pistol – still are!”

I then pressed him to choose a “winner.” After a few moments of hesitation he said, “The M&P. But then I’m prejudiced.”

NOTE: I would like to thank Vincent Scarlata, John Rasalov, Charles Pate, Michael Jon Littman, Donna Wells, Jeff Hoffman and Clive Law for supplying materials used to prepare this report. And I’m indebted to Black Hills Ammunition (PO Box 3090, Rapid City, SD 57709. Tel. 800-568-6625) for their kind cooperation in furnishing ammunition.

This article is an excerpt from Gun Digest 2010.

Next Step: Get your FREE Printable Target Pack

Enhance your shooting precision with our 62 MOA Targets, perfect for rifles and handguns. Crafted in collaboration with Storm Tactical for accuracy and versatility.

Subscribe to the Gun Digest email newsletter and get your downloadable target pack sent straight to your inbox. Stay updated with the latest firearms info in the industry.

![Best Concealed Carry Guns In 2025 [Field Tested] Wilson Combat EDC X9S 1](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Wilson-Combat-EDC-X9S-1-324x160.jpg)

![Best 9mm Carbine: Affordable PCCs [Tested] Ruger Carbine Shooting](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Ruger-Carbine-Shooting-100x70.jpg)

![Best AR-15: Top Options Available Today [Field Tested] Harrington and Richardson PSA XM177E2 feature](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Harrington-and-Richardson-PSA-XM177E2-feature-100x70.jpg)

I need this gun

Leave

Pistol

Kerala Kozhikode kovoor 673017 8137916925