NO JOHNNY REB manning the Confederate line at Mayre’s Heights could be unimpressed at the spectacle before him. On an open plain between this high ground and the nearby town of Fredericksburg, Virginia, thousands of Federal troops were massing for an attack.

William M. Owen, a Confederate artillery officer, watched on December 13, 1862, as the enemy soldiers ran toward him behind unfurled battle-flags, chanting a deep-throated refrain — Hi! Hi! Hi! “How beautifully they came on,” he wrote years later. “Their bright bayonets glistening in the sunlight made the line look like a huge serpent of blue and steel.”

Union Major General Ambrose E. Burnside was hurling his Army of the Potomac against the Southern defenses. He wanted to rout General Robert E. Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia, and then march into Richmond about 50 miles south and end the war. Burnside had massed 27,000 men for the attack on Mayre’s Heights; Lee had only 6000 defending it. Although Federal assaults earlier that day had failed elsewhere along Lee’s line, Burnside hoped this attack would work.

The Union attack, however, was doomed to fail. Lee held a superb defensive position. Mayre’s Heights commanded nearby terrain and was studded with artillery. At its base, a breast-high stone wall provided shelter for the Georgia infantrymen of Cobb’s Brigade. Also, many of Lee’s men had rifled muskets, the war’s most common infantry weapon. A properly trained soldier could hit tar gets at 300 yards, firing three rounds a minute.

That so many of these weapons would be in Southern hands was a miracle. When the various states that comprised the Confederacy left the Union in 1860 and 1861, they had few modern military rifles. U.S. arsenals seized by the South held older, less-desirable guns.

Plus, the South had virtually no rifle-making facilities. Perceptive Southern leaders knew that a Union naval blockade eventually could slow, and probably halt, imports. All these factors produced an ill-armed military.

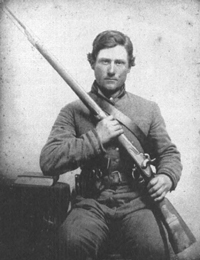

“At the commencement of the war, the Southern army was as poorly armed as any body of men ever had been,” wrote John H. Worsham of the 21st Virginia Infantry Regiment. “Using my own regiment as an example, one company of infantry had Springfield muskets, one had Enfields, one had Mississippi rifles, and the remainder had the old smoothbore flintlock musket that had been altered to a percussion gun.

The cavalry was so badly equipped that hardly a company was uniform. Some men had sabers and nothing more, some had double-barreled guns. Some had nothing but lances, and others had something of all. One man would have a saber, another a pistol, another a musket, and another a shotgun. Not half a dozen men in the company were armed alike.”

That situation had changed dramatically by late 1862, as Burnside and his men learned at Fredericksburg.

Federal commanders initiated the attack around noon. Their men had to cross about 600 yards of open ground to reach the Confederate position. Union troops began taking casualties as soon as the advance started.

When they were within 125 yards of the stone wall, Cobb’s infantrymen shouldered their muskets.

“A few more paces onward and the Georgians in the road below us rose up, and, glancing an instant along their rifle barrels, let loose a storm of lead into the faces of the advanced brigade,” Owen wrote.

“This was too much; the column hesitated, and then, turning, took refuge behind the (nearby earthen) bank.”

Burnside repeatedly sent assault waves against the enemy lines all day. Only the arrival of night ended the fighting. No Billy Yank came closer than fifty yards to the stone wall. Federal losses were 8000 compared to 1600 for the South.

Fredericksburg was a testament to the Army of the Potomac’s courage. It also showed that the rifled musket was ending the sweeping, grand Napoleonic charge. This weapon represented a significant technological gain in warfare.

It was powerful enough, accurate enough and had enough range to pound apart the most determined attack a foe could mount. The industrialized North could supply hundreds of thousands of these arms to its soldiers with comparative ease.

The agrarian South, however, faced staggering supply problems. Against all odds, the Confederacy did get sufficient modern arms to its troops. That required hard work, organization, improvisation and the talents of a remarkable man — Josiah Gorgas. Nobody in the Confederacy would do more to get rifles for Johnny Reb.

A Pennsylvanian, West Pointer and pre-war professional soldier, Gorgas became chief of Confederate ordnance early in the war. Before it ended, he would run thousands of guns through the Yankee blockade and build a Southern weapons industry from scratch.

Southerners in 1861 might have gone to war with fowling pieces and old smoothbores, but by mid-1863, thanks to Gorgas, they generally had equipment that matched their Federal foes’. One Southern leader succinctly and accurately described his wartime achievements: “He created the ordnance department out of nothing.”

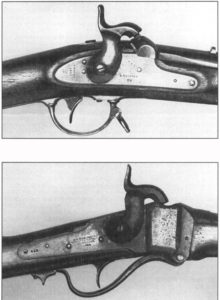

Gorgas knew early on that the rifled musket would play a key role in the conflict, and the Confederacy would need large quantities of them. He also understood its capabilities. Compared to today’s military rifles, the typical Civil War musket was heavy, big, cumbersome and fired a huge bullet, often more than half-an-inch in diameter. Such muskets required twenty steps to load. A soldier typically did this standing upright and holding his weapon in front of him with its butt on the ground.

Ammunition came in paper cartridges that contained a bullet and a standard charge of blackpowder. Johnny Reb would bite off a cartridge end, pour the powder down the barrel, discard the paper, place the bullet in the muzzle and ram it to the breech using a ramrod carried in a channel beneath the barrel.

The Civil War musket’s ignition system relied on the percussion cap, a metal cap filled with fulminate of mercury. The system was reliable and could function in all weather conditions.

The same could not be said of the previous generation of military shoulder arms. The flintlock muzzleloader depended on a piece of flint striking a piece of metal to create a spark. Much could go wrong with this process, and damp powder doomed it. Knowing the flintlock’s limitations, both Civil War armies eagerly embraced the percussion system.

Average Johnny Rebs and Billy Yanks in the infantry used the same weapons and used them the same way, both as individuals and as members of military units.

For much of the conflict, officers in blue and gray deployed troops in large, concentrated units that shot in volleys. This allowed commanders to mass fire and to control fire rates. The only way to move men into these combat formations was through standardized maneuvers, which explains why the 19th century American soldier spent much time drilling.

Although presented with a powerful, comparatively long-range weapon in the rifled musket, generals stuck with those formations and tactics appropriate to the short ranges and inaccuracy of the smoothbore era. Surprisingly enough, leading commanders on both sides failed to immediately grasp the rifle’s destructive power.

Not only did Burnside embrace the frontal assault at Fredericksburg, but so did Lee at Gettysburg, Ulysses S. Grant at Cold Harbor, and Confederate Lt. Gen. John B. Hood at Franklin, Tennessee. At all these places, the results were disastrous.

As the war progressed, however, the average soldier realized the value of entrenching. Southern infantrymen became adept at creating trenches and rifle pits whenever they stopped, using tin cups and plates as well as shovels to put a few inches of dirt between them and the enemy. The 1864–65 Petersburg campaign, in fact, was largely a fight between entrenched armies that knew a direct attack against such works was tantamount to suicide.

For the average Confederate soldier, combat was a terrifying experience. It also was hard work. To begin, loading the rifle was difficult. Even veteran soldiers could easily forget what they were doing in the heat of battle.

Sometimes they loaded a bullet first, powder second, or jammed load after load down the barrel without capping the nipple. Blackpowder also quickly clogged musket barrels and wrapped the battlefield in clouds of dense smoke that made seeing targets difficult, if not impossible.

Johnny Reb also endured his rifle’s hefty recoil. Sam Watkins, a Southern soldier, reported firing 120 rounds during the Battle of Kenesaw Mountain. Afterwards, his arm was battered and bruised. “My gun became so hot that frequently the powder would flash before I could ram home the ball,” he wrote, “and I had frequently to exchange my gun for that of a dead colleague.”

How good a shot was Johnny Reb? We’ll probably never know. While the rifled musket could perform outstandingly, and many Southerners lived in a society that prized good guns and marksmanship, battle imposed great demands on the best of shots.

The danger, excitement, loading process and smoke-covered battlefields made accurate shooting extraordinarily difficult. One historian has estimated that for every casualty produced, 200 rounds were fired. Others believe the figure to be much higher.

If the tactical implications of the rifled musket were sometimes imperfectly understood, its value as an improved shoulder arm was easily grasped.

So Confederate officials knew that getting these weapons into Johnny Reb’s hands was vital, and Confederate ordnance chief Gorgas energetically set to work on the problem from the war’s start. He knew only three sources of supply existed: capture, import and Southern manufacture.

The Confederacy turned to capture first. As each Southern state left the Union, it seized any Federal arms held at arsenals or armories within its borders. The pickings were lean.

These establishments did not have many modern arms. They mainly held older government models of little value. Among these was the U.S. Model 1822 musket, a 69-caliber smoothbore.

Many were converted from flintlock to percussion, but the improved ignition system did not compensate for their unrifled barrels. Their range and accuracy was limited. Hitting a specific target more than 100 yards away relied on luck as much as skill.

Once the fighting began in earnest, the Confederacy wasted little time in seizing modern Union weapons whenever they became available. Federal prisoners, battlefield gleanings and captured warehouses yielded first-class arms for the Cause.

As veteran Southern infantryman Worsham noted: “When Jackson’s troops marched from the Valley (of Virginia) for Richmond (in 1862) to join Lee in his attack on McClellan, they had captured enough arms from the enemy to replace all that was inferior; and after the battles around Richmond, all departments of Lee’s army were as well armed.”

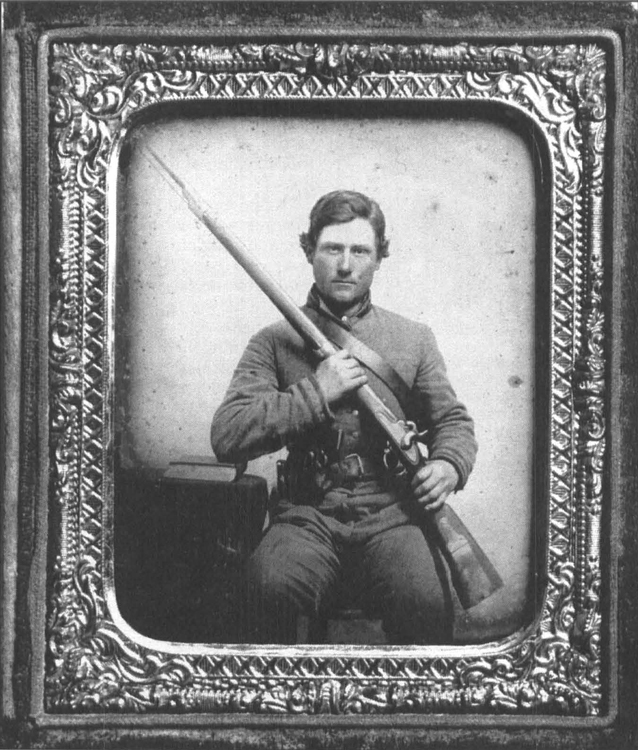

Probably the most preferred capture from the Yankees was the 58-caliber Springfield, which came in several models. This rifled musket was superior and typical of its type. The weapon weighed roughly 9 pounds, was 58 inches long, and saw more service with the U.S. Army than any other rifle. Government and private armories produced hundreds of thousands during the war.

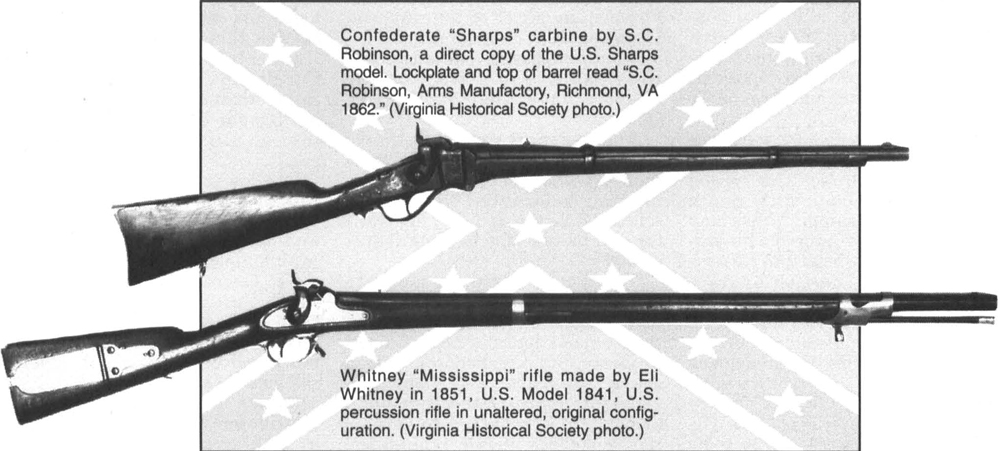

Also especially desired by Johnny Reb was the U.S. Model 1841. It was first issued in 54-caliber, but many were altered to 58-caliber, and a fair number came into Confederate hands through Federal arsenals in Southern states. This weapon was commonly known as the “Mississippi rifle,” from its Mexican War service with Mississippi volunteers commanded by Jefferson Davis.

Confederates also were delighted to get their hands on Federal breechloaders like the Sharps and Spencer. Both represented significant gains in rates of fire and ease of loading.

To load the Sharps, a 52-caliber breechloader, the soldier pulled down the trigger guard. This caused the breechblock to drop and opened the chamber into which was inserted a linen or paper cartridge filled with powder and a bullet. The Sharp’s rate of fire was three times that of a musket.

The Spencer fired metallic cartridges. Its tubular magazine in the buttstock held seven rounds.

A skilled operator could fire twenty-one rounds per minute. Unfortunately for the South, captured Spencers suffered from an ammunition shortage as the Confederate industry frequently was incapable of meeting cartridge needs created by the weapon’s firepower abilities.

Though infantrymen seldom carried revolvers, the Confederate cavalry loved them, especially captured Colts. These were Northern-made, but saw widespread use in both armies. Six-shooters in 36- and 44-calibers, their cylinders could be loaded with paper, foil or sheepskin cartridges, or loose powder and ball. Ignition required a percussion cap on each nipple at each chamber.

Imports were another vital source of armaments. Europe eagerly provided guns to both sides. Southern weapons had to come through the Federal blockade, and a surprisingly large volume made the trip.

Europe offered some superlative weapons and some junk. Particularly despised by Johnny Reb were rifles made in Austria and Belgium. Unwieldy, inaccurate and unreliable, they were dead last on his wish list.

The most desired import was the 577-caliber Enfield. A British-made musket, the Enfield was rugged and accurate. The Enfields came in several styles, including a carbine. Southern cavalry was particularly attached to the latter, even though as a muzzleloader it lacked the rapid-fire quality of Union repeaters. Another popular and well-crafted British import was the 44-caliber Kerr revolver.

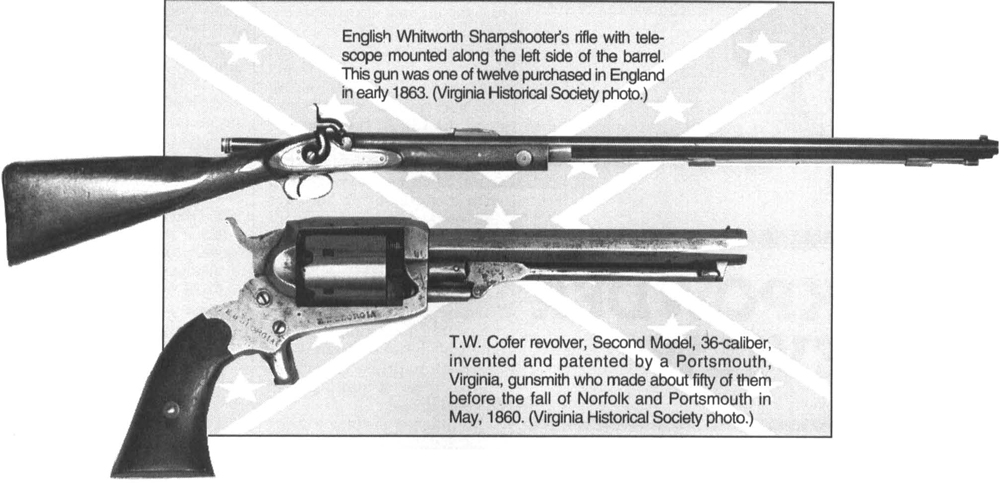

Great Britain also supplied some of the war’s best sharpshooter rifles: the 44-caliber Kerr and 45-caliber Whitworth. Southern marksmen treasured these guns, which enabled them to hit targets at 1000 yards. The most famous long-range shooting incident of the war occurred on May 9, 1864, during the Battle of Spotsylvania.

Several Southern marksmen are given credit for what happened, but it is impossible to know who did the shooting. One version of the incident comes from Captain William C. Dunlop who commanded the sharpshooters of McGowan’s Brigade.

This Confederate unit was ordered to move ahead of the main body of Southern troops to scout for Federals that day. Dunlop concealed his men in position along a ridge where they could see the Union VI Corps deploying on a distant hill. Immediately, Dunlop’s men began firing with telling effect.

Among Dunlop’s troops was a Private Benjamin Powell of South Carolina, who carried a Whitworth that day and was looking for important targets. One soon presented itself. Powell could see a Yank officer moving along the enemy firing line, giving commands and viewing the field through binoculars. His behavior and the staff trailing behind him suggested this was an important man.

Powell decided to shoot him. The round traveled 800 yards and struck General John Sedgwick, the corp commander, in the left cheek, killing him. Only moments earlier, the general had tried to calm his troops who were agitated by the sniper fire. They “couldn’t hit an elephant at this distance,” he said seconds before he died.

One of the most intriguing weapons that made it through the Union’s naval blockade was the Le Mat revolver, which could fire nine 41-caliber rounds from its main barrel plus buckshot from a shorter one. (Oddly enough, its main barrel’s caliber is variously reported as ranging from 40- to 42-caliber.)

The idea for this monster came from Jean Alexander Francois Le Mat, a New Orleans doctor. Once the Confederacy accepted his pistol, the doctor headed for France where it was produced. A carbine model also was developed.

The last source of weapons was from within the Confederacy. Given the virtually non-existent manufacturing base there, Gorgas achieved astonishing results, creating government armories as well as inspiring various private firms to enter the armaments field.

The best Southern-made weapons came from government operations in Richmond and Fayetteville, North Carolina. Early in the war, the Confederacy captured Federal gun-making equipment at Harper’s Ferry. This was used at both Confederate plants to produce 58-caliber muskets, known as Richmond and Fayetteville rifles.

These two factories were not the only source of “home-grown” weapons. Other production facilities sprang up in Georgia, Louisiana, South Carolina, Mississippi, Texas and Alabama. Quality and volume varied greatly from factory to factory, as the case of the Confederate “Sharps” proved. These were versions of the Sharps carbine Model 1855, made by the Richmond firm of S.C. Robinson Arms Manufacturing Company.

Forty were sent for field-testing to the 4th Virginia Cavalry Regiment in the spring of 1863. The gun was not a success. Reportedly seven of nine burst during firing. Furious, an officer of the regiment, Lieutenant N.D. Morris, fired off a letter to a newspaper, The Richmond Whig, which ran a story on the weapons under the headline “An Outrage.”

“The lieutenant suggests,” ran the article, “that the manufacturers of these arms be sent to the field where they can be furnished with Yankee sabres, while the iron they are wasting can be used for farming implements!”

Ordnance officials rushed to defend the producers and the carbines, suggesting the soldiers using the weapons had not been trained properly, but the bad reputation stuck. Captain W.S. Downer, superintendent of the Richmond armory, also reported to Gorgas that somebody should remind the letter-writing lieutenant about army procedures.

“I would also suggest that Lieut. N.D. Morris, of Capt. McKinney’s Co., 4th Va. Cavalry, be notified to communicate with the Department through his proper officers, rather than through the columns of a newspaper.”

Besides government plants, private firms got involved in weapons production. For example, Davis and Bozeman of Coosa County, Alabama, made 58-caliber rifles. J.&F. Garrett Co. of Greensboro, North Carolina, produced the 52-caliber Tarpley carbine, the only breech-loading gun patented, manufactured and offered for general sale in the Confederacy.

Private industry made its biggest contribution to weapons production by making pistols. When the war began, the Confederacy had no revolver manufacturers within its borders. But wartime entrepreneurs appeared like Spiller and Burr, Griswold and Gunnison, and Leech & Rigdon.

Many entrepreneurs found that making weapons for the South was a difficult business indeed. Consider the story of Charles Rigdon, for example, a Southern sympathizer who lived in St. Louis. He moved to Memphis when the war started and formed a partnership with Thomas Leech to make swords.

Advancing Union armies forced the pair to move to Columbus, Mississippi, and then to Greensboro, Georgia, where they made 36-caliber revolvers, which were copies of Colt’s pistols.

The partnership eventually collapsed. Leech kept making revolvers in Greensboro. Rigdon opened a new pistol firm in Augusta, Georgia — Rigdon, Ansley & Co. — that operated until the war’s end. Interestingly enough, Samuel Colt sued the company for illegal use of his revolver patents.

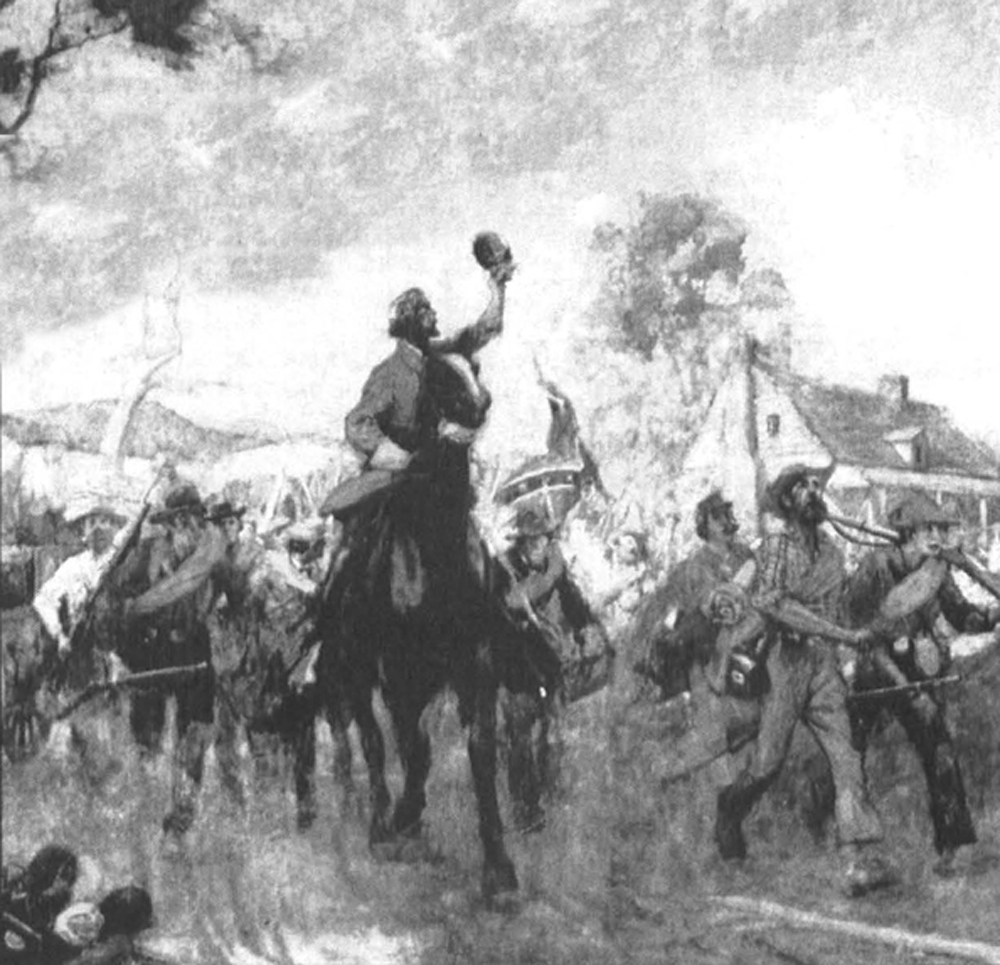

One non-issue weapon that came from private manufacturers was the shotgun. Often brought from home, shotguns were popular among certain Confederate cavalry units, particularly in the Western Theater.

Shotguns had limited range, limited tactical value and took a long time to load. But at close quarters they were devastating. The 8th Texas Cavalry, better known as Terry’s Texas Rangers, were particularly fond of scatterguns.

During the Southern retreat from the Battle of Shiloh, this unit used these weapons effectively. Ordered to charge Union infantry pursuing the Southern army, the Texans swept forward, halted about twenty steps from the Federal line and fired their shotguns.

Each barrel was loaded with fifteen to twenty buckshot. The Federal pursuit fell apart and a retreat ensued. The Texans then put their shotguns aside and pursued the enemy on horseback, firing their revolvers.

Much of the success of Southern weapon production came from the use of slave labor. African-Americans worked in armories and played a key role in the armament industry’s labor force. For instance, the Georgia pistol firm of Columbus Fire Arms Manufacturing Co. hired forty-three blacks in 1862 and aggressively tried to find more during the rest of the war.

For blacks, working in weapons production was a mixed bag. It often meant separation from loved ones, hard work, long hours and daily rations of bacon and cornmeal. However, the work gave them valuable skills and provided an unprecedented degree of freedom.

Although the Confederacy ultimately lost the war, it did not do so due to a lack of weapons and ammunition. Granted, the Southern ordnance system had flaws. Armies in the East tended to be better supplied than those in the West.

Units in either theater, even late in the war, might carry a hodgepodge of weapons, mostly rifled muskets but sometimes smoothbores, and this variety made ammunition re-supply a headache. Some of the Southern-made rifles and pistols did not meet the standards of Northern or British factories, but on balance Gorgas did a remarkable job.

One anecdote makes the point. When Lee surrendered at Appomattox in 1865, his army was small, sick, ill-clad and poorly fed. However, most men were armed and, on average, each carried seventy-five rounds of ammunition.

Today, Confederate guns are scarce and costly. But the interested student of Civil War firearms can see one of the world’s best collections of Southern weapons at the Virginia Historical Society in Richmond.

The society owns an extraordinary collection of rifles, pistols, swords, belt-plates and buttons given to it in 1948 by Richard D. Steuart, a Baltimore newspaperman who had two grandfathers and nine uncles who served the Confederate cause. For many years, the collection was displayed to feature the weapons themselves as artifacts and objects of interest.

In 1993, the Virginia Historical Society decided to display its collection in an innovative way. The weapons were moved into a gallery decorated with life-sized murals of Civil War battle scenes. The new display uses the guns to tell the story of how the South armed itself. For the neophyte or life-long scholar of the conflict, the new display is entertaining and informative — you can see Johnny Reb and his guns.

This article is an excerpt from the Gun Digest Book of Classic Combat Rifles.

Next Step: Get your FREE Printable Target Pack

Enhance your shooting precision with our 62 MOA Targets, perfect for rifles and handguns. Crafted in collaboration with Storm Tactical for accuracy and versatility.

Subscribe to the Gun Digest email newsletter and get your downloadable target pack sent straight to your inbox. Stay updated with the latest firearms info in the industry.

![Best Concealed Carry Guns In 2025 [Field Tested] Wilson Combat EDC X9S 1](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Wilson-Combat-EDC-X9S-1-324x160.jpg)

![Best 9mm Carbine: Affordable PCCs [Tested] Ruger Carbine Shooting](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Ruger-Carbine-Shooting-100x70.jpg)

![Best AR-15: Top Options Available Today [Field Tested] Harrington and Richardson PSA XM177E2 feature](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Harrington-and-Richardson-PSA-XM177E2-feature-100x70.jpg)