The history of Oliver F. Winchester (1810-1880) and his endeavors in the manufacturing of fire-arm sat Bridgeport and New Haven, Connecticut, is filled with circumstances that could have led to corporate failure. However, Winchester and his succeeding family members successfully managed Winchester Repeating Arms Company from 1866 to 1919. During that time they largely made the right business decisions, hired the right people, and enjoyed a fair share of luck. That luck ran out following World War I when the arms industry declined and the management of Winchester was relinquished to outsiders.

Harold Williamson, in his book Winchester, The Gun That Won the West, relates that the new management of Winchester embarked “on a program that involved an extraordinary departure from the company’s previous operations and the investment of borrowed capital in large amounts.” Winchester struggled through a decade of inept product diversification that was terminated by the Great Depression. Winchester was bankrupt and went into receivership in January 1931. The committee appointed to study the requirements for continuing business reported “a successful reorganization would require the raising of a substantial amount of new capital.” That capital was supplied by the Olin family of Olin Industries, owners of Western Cartridge Company.

Franklin W. Olin founded Western Cartridge Company in 1898. Western rapidly achieved a leading position in the ammunition industry through innovation and skillful management. Franklin and his two sons John M. Olin and Spencer T. Olin were the managers of Olin Industries and Western Cartridge Company in 1931. The Olins bought Winchester for $8.1 million through a combination of $3.3 million cash and the balance in an issue of preferred stock. The Olins used the Western ammunition plant at East Alton, Illinois, as collateral for borrowing about four million in cash, no small feat in the fall of 1931. The survival of both Western and Winchester now depended on Olin management.

Edwin Pugsley, in charge of Winchester at the time of receivership, is quoted in Williamson’s book: “ The purchase of the company by the Olin interests brought a breath of life to the institution and brought to Winchester many things. First of all was the end of management by people who were not familiar or sympathetic with the gun and ammunition business.” The Olins were avid duck hunters.

It was John Olin who inspired Western’s revolutionary “Super-X”shotshell in 1921. The short shot string put more shot into a duck whistling by at 50 yards. Western’s 3-inch 12-gauge magnum with 1 3/8-ounces of shot was introduced the same year. The magnum led to new class of long-range double-barrel shotguns for waterfowl. Western’s copper-plated shot, introduced about 1925, extended shotgun range even further. It was Western that produced the 3 1/2-inch 10-gauge magnum with 2 ounces of shot in 1932.

Ithaca brought out their “Magnum 10”double to use the new shell. John Olin wanted a new 3-inch .410 shotshell with 3/4-ounce of shot for Winchester’s new Model 42. Winchester designed the Model 42 to use the new shell and the combo went to market in 1932. The duck gun version of the Model 12, introduced in 1935, was a natural consequence of duck hunters in charge of Winchester. The Model 12, already 23 years old, was one of many successful designs by Thomas C. Johnson.

Thomas C. Johnson came to Winchester in 1885 and remained a dedicated employee until his death in 1934. Johnson, at once one of the great gun designers and one of the least known, produced a steady flow of new firearm designs for Winchester. Initially came a series of auto-loading rifles, including the rimfire Model 1903 and centerfire rifles, culminating with the Model 1910, chambered for the 401 WSL cartridge. Johnson designed the Models 52 and 61 rimfire rifles and the Model 54 centerfire rifle. He was the chief designer of the Model 21 double, John Olin’s favorite. However, the gun for which Johnson is best remembered is his Model 12 pump-action shotgun, “The Perfect Repeater.”

The Model 12 shotgun, initially the Model 1912, hit the market in August 1912. It was an immediate success. Sales of 100,000 were recorded in the first two years of production. Thereafter, a staggering number of variations were produced during the 1912-1980 period. Total production reached two million. Dave Riffle in his book, The Greatest Hammerless Repeating Shotgun Ever Built: The Model 12 1912-1964, states “The Winchester Model 12 was, and still remains, the only gun that was offered in over 100 different variations or configurations during its lifetime.” It is fair to say that Winchester produced Model 12 shotguns for every conceivable shotgunning special interest group, including duck hunters.

The Model 12 Duck Gun is a highly specialized tool for hunters who need to put a lot of shot on target at 60 yards or more. The duck gun’s reputation was made with the one and five-eighths ounce load, the heaviest 12 magnum load from about 1935 to the mid-1950s.

The Gun and the Times

The Model 12 duck gun examined by the staff of the American Rifleman in 1936 was the earliest version. The stock has a hard-rubber plate and a real, full pistol grip carved close to the guard. It is the skeet style of stock with a comb drop of 1 1/2 2 1/2 inches, and a 14-inch length, butt to trigger.

The gun weighed 8 1/2 pounds with its 32-inch Full choke barrel. “The receiver is heavier and so is the barrel. The balance point is the takedown joint. It is not as slow or pokey as one might expect.” The staff shot skeet with the gun and concluded “It is not as fast as the standard Model-12, but nearly so.”

In further shooting tests the staff found “We could not discern any practical difference in recoil effect when shooting standard three inch heavy duck loads.” Winchester supplied two boxes of 3-inch shells loaded with 1 3/8-ounces of #5 chilled shot pushed by four drams equivalent of powder. The load averaged 67.5% (range 62-72.5%), in a 30-inch circle at 40 yards. This percentage was disappointing compared to the 80% or better patterns obtained with other duck guns tested by the staff. An 80% pattern they felt “should make it a real 60-yard outfit with No. 4 chilled shot.”

The new Model 12 duck gun was introduced to long-range waterfowl hunters habituated to heavy double shotguns chambered for 3-inch shells. The 3-inch shell was chambered originally in the famous Super Fox long-range double.

Jack O’Connor was there and sets the scene nicely in the Complete Book of Shooting. “Along in the 1920’s a few bold souls had long-chambered [3-inch], overbored, long-barreled, and heavy, long range 12-gauge Magnum double guns built. These were turned out by the Hunter Arms Company of Fulton, N.Y. in L.C. Smith brand, by the A.H. Fox Company of Philadelphia, by Parker, and by Ithaca. These were called long-range waterfowl guns.”

The Model 21 double seemed the reasonable choice for Winchester’s duck gun. Thus it was that the American Rifleman staff thought it odd that Winchester brought out the 3-inch chamber in their Model 12 pump gun. Charles Askins may have influenced the decision.

Charles Askins was the leading expert on shotguns in the first half of the last century. He spent many years as firearms editor for Outdoor Life and later Field and Stream, as well as shotgun editor for the American Rifleman. Askins wrote in his 1929 book Modern Shotguns and Loads: “Perhaps half the game that is killed in America today is shot with repeating shotguns, pump or automatic. In duck shooting the proportion of magazine guns in use is much higher, probably four men in five using the repeater.” Askins added, “Fact is, personally, I have always thought that I was surer on the second bird with a repeater than I was with a double gun.” On gauges for duck hunting: “No fault is to be found with the twelve [gauge] as a duck gun, whether in double barrel with 3 inch cases or in repeaters with 2 3/4 inch”.

Since “Every shotgun manufacturer is a friend of mine”, Askins’ views were well known in the industry. The Olins were businessmen first and duck hunters second. In their view, the Model 12 pump with 3-inch chamber was likely to sell better than a similarly chambered Model 21 double. The Model 21 received duck gun status in 1940, although 3-inch chambers could be ordered earlier. The Model 12 was the first magazine repeater chambered for 3-inch magnum shells.

Charles Askins commented on the new Model 12 duck gun in the March 1936 issue of Outdoor Life: “This should be the best long-range repeating shotgun now made or that has been made.” No faint praise, but hardly a surprise.

The Olins soon added to the attractiveness of the Model 12 duck gun by bringing out a new 1 5/8-ounce load for the 3-inch shell. Here-tofore, you could only shoot this weight of shot in a 10-gauge double gun with 2 7/8-inch chambers, or the new Ithaca Magnum 10. Fanciers of long-range shotguns now had a 12-gauge repeater shooting a 10-gauge shot load. The $48 price tag was right. Enthusiastic hunters bought the new repeater.

George Madis indicates in his book The Winchester Model Twelve that about 18,000 Model 12 duck guns were sold during the 1935-1941 period. The magnitude of this sale is appreciated when you realize how few of the special 10- and 12-gauge magnum double guns were sold. A study of Michael McIntosh’s book Best Guns indicates that a few thousand of the specialized waterfowl doubles of all brands were sold between 1921 and 1941. For example, only about 300 Super Fox and 800 of the Ithaca Magnum 10 doubles went into hunter’s hands during the period.

The era of the double gun was ending as World War II approached. The era of plentiful ducks and liberal bag limits was also ending. The Model 12 duck gun came to market at the all-time low point of duck populations in the United States. Severe drought conditions gripped the United States and Canada during the 1930s. Reduced bag limits and shell capacities for repeating shotguns were introduced. The Duck Stamp Law of 1934 was enacted to provide funds for waterfowl propagation. The Pitt-man-Robertson Act of 1937 began an 11 percent excise tax on sporting arms and ammunition. The funds are returned to the states for wildlife restoration projects. Ducks Unlimited was born in 1937 to aid in restoration of wetland breeding areas, primarily in Canada. Winchester recognized the scarcity of ducks in their promotional advertisement of the new duck gun “To Meet the New Wildfowling Conditions.” I suspect most Model 12 duck guns bought before World War II were put to work on other game.

Winchester made changes to the stock of the Model 12 duck gun after its introduction. A red rubber Winchesterre coil pad was added the first year of production. Length of pull was reduced in January 1936 to reflect the extra clothing worn by duck hunters. The drop at heel was reduced from 2-1/2 to 2-3/8 inches in December 1938.

The straighter stock reduced perceived recoil. Down pitch remained 2-1/2 inches with the 30-inch barrel throughout production. The less pronounced pistol grip-style buttstock of the original Model 12 was discontinued in late 1934 and is not found on duck guns. The new 1935-style buttstock featured a closer and fuller pistol grip. The buttstock was reshaped on Model 12 shotguns again in the mid-1950s. The late style stock featured a flared pistol grip moved back a bit from the trigger. In 1960, length of pull was increased to 13-3/4 inches on duck guns. The straight grip stock, optional from 1935, was discontinued in the late 1950s.

Buttstocks of duck guns had lead slugs inserted into the wood beneath the recoil pad. The lead slug added weight but more importantly maintained the balance point at the takedown joint. Madis comments “Fancy walnut was considered too fancy for the rough treatment often given a duck gun.” Fancy walnut could be ordered and the few pidgeon-grade duck guns had fancy walnut. Some late duck guns came with special order Hydro-Coil stocks, according to Madis.

The slide handle of early duck guns was round with 18 circular grooves. The slide handle was given a larger diameter, flat bottom and 14 grooves on each side of the handle about 1947. The slide handle was enlarged in about 1956 to a slightly extended beaver tail shape with 14 circular grooves. Keep in mind that all of these changes in stock design were “running changes” and thus some overlapping of designs occurred in production.

The barrels and receivers of Model 12 duck guns are made from “Winchester Proof Steel.” This steel was first used in the Model 21 double introduced in 1931. Winchester proof steel replaced nickel steel in the manufacture of all Winchester firearms in the early 1930s. Winchester proof steel is chrome-molybdenum steel. In an ad in the October 1952 American Rifleman, Winchester proclaimed. “Metal parts of the Model 12 are machined from chrome-molybdenum, the toughest, longest wearing and finest gun steel known.” Barrel lengths were 30 or 32 inches, but 32-inch barrels were discontinued in 1948. Full choke was the only standard boring available. Winchester cautiously claimed “70 to 75% pattern in a 30 inch circle at 40 yards.”

Madis states “Ventilated ribs were rarely offered on [duck] guns.” However, “The fact is a few duck guns were provided with these ribs.” Dave Riffle’s book and the various catalogs I have indicate that the Winchester new ventilated rib was an option from about 1954 to 1959. Only rib extensions of the same width as the factory ventilate drib are found on receivers of duck guns. Ronald Stadt states in Winchester Shotguns and Shot-shells: “All Winchester special ventilated rib magnum guns examined have sand-blasted receiver tops.” Solid ribs were offered until the mid-1950s, except as noted by Stadt: “The 1960 wholesale-retail catalog listed 30-inch solid rib pidgeon magnums. This likely was the last mention of solid ribs in Winchester literature.” The duck gun was discontinued in 1963.

Model 12 duck guns had the same six-shot capacity as the standard Model 12: one in the chamber, five in the magazine. President Roosevelt signed the law limiting magazine repeaters to three shells for migratory game bird hunting in 1935. Winchester dutifully shipped its duck guns with a wooden plug installed to limit magazine capacity to two shells.

Winchester stated both “2 1/2 and 2 3/4” shells perform satisfactorily in this [duck] gun.” The ejection port of the duck gun is about 1/8-inch longer than the standard port. Recent 3 1/2-inch 12-gauge shells will create dangerous pressure in the 3-inch duck gun chamber. Winchester advises “Do not use steel shot in any Winchester shotgun with a fixed choke.” Use tungsten polymer, tungsten matrix or bismuth shot for waterfowl hunting with your Model 12 duck gun.

Mechanically, the Model 12 duck gun differs little in design from the standard Model 12. In fact, Madis states “Any twelve gauge Model Twelve could be re-chambered and reworked to shoot three inch shells for a small additional charge[by Winchester], yet few guns were reworked in this way.” I can find no external differences in receiver dimensions, other than the ejection port, between standard and magnum versions.

All Model 12 shotguns have an action slide lock that keeps the action closed and locked in the event of a misfire or hang-fire. If you pull the trigger and the shell does not fire you must push the slide handle forward to unlock the action. Consider the possibility of a hang-fire, an occasional event in 1912, in a gun without the slide lock feature. You jack the shell out and it goes off under your nose. The slide lock is automatically released by the forward nudge of recoil in the Model 12. Later pump guns, such as the Remington Model 870 and Mossberg Model 500, do not have the slide lock feature. It is possible for the slide lock to fail to unlock the action during recoil. The duck gun sent to the American Rifleman staff in 1935 would not unlock during recoil.

“Most annoying was the failure of the action-slide lock to function properly. Its failure to release on discharge made it impossible to shoot doubles [at skeet] with this particular sample.” The staff concluded, “Mechanically, the sample was not as good as other guns of the same model.” Noted were machine marks on the breech bolt, wood not closely fitted, primers struck off center and sharp edges at the chamber. Could it be that the intended rough usage led to lack of care in the fitting of parts of early duck guns?

Winchester undertook preparations for improvements in its firearms line following World War II. John Olin initiated an analysis of Winchester’s commercial line in 1942. George Watrous, a longtime Winchester employee with many talents, was commissioned to investigate the good and bad points of Winchester’s pre-war line and make suggestions for postwar improvement.

Herbert Houze summarizes the Watrous report in his book Winchester Repeating Arms Company, Its History & Development from 1865 to 1981. Houze relates that for the Model 12 the Watrous report suggested “improve the smoothness of the action as it is criticized for being rough.” How this was to be accomplished is not related but closer hand-fitting and gauging of parts was likely.

Model 12 duck guns could be ordered in pidgeon grade, featuring fancy wood and meticulous fitting and finish of parts. Also available initially were standard trap and special trap grades. Checkered stocks and extension slide handles were available as options on the standard grade throughout most of the duck gun’s production. Interchangeable barrels (forend assembly) for 2 3/4-inch shells and choke of choice were special order. Optional dimensions for straight or pistol grip stocks, grip caps, front sights and recoil pads were also among early options.

Options for the Model 12 duck gun were reduced over the years, particularly following World War II. This was a result of the Watrous report, which recommended that many of the slow-selling options be discontinued following the war. By 1955, the options were matted rib, ventilated rib, straight or pistol grip stock and buttstock and extension slide handle checkered. The pidgeon-grade duck gun was discontinued in 1961. In 1963, when production ended, Riffle’s book shows no options available. The price in 1963 was $122

compared to $109.50 for the standard Model 12. Duck guns always sold for a slight premium over the standard model.

3-inch “Super Twelve” Shotshell

My copy of Winchester’s Catalog No. 80 of 1916 indicates seven empty 12-gauge paper shell lengths (2-1/2 to 3-1/4 inches). The “standard length” was 2-5/8 inches. There are 16 pages of loads for various shell lengths, shot sizes (dust through buck, soft or chilled), five powders, five shell grades and 11 gauges. There was only one way to go after World War I: standardize shell lengths, discontinue bastard gauges and reduce the load options. The standard 12-gauge duck load in 1921 was a 2 3/4-inch shell holding 3 3/4-drams equivalent powder and 1 1/4-ounces of shot.

Western brought out their Super-X 2-3/4 and 3-inch shotshells in 1921. McIntosh notes that the Super-X shotshell “was a breakthrough to the modern age of shotgun ammunition.” In a full-page ad in the September 1926 issue of the American Rifleman, Western claimed “Killing power 15 to 20 yards beyond the effective range of ordinary loads.”This was based on a documented reduction in stringing of the shot charge, from about 20 feet to about 4 feet, at 42 yards. My 1951 Winchester Ammunition Handbook gives a comparison of 17 to 11 feet at 60 yards. Western’s innovation was progressive-burning powder that deformed fewer shot during acceleration. Charles Askins confirmed the tighter patterns and greater effective range in the field. Duck hunters bought 12-gauge doubles with 3-inch chambers to use the new Super-X magnum load, the Super Twelve as it was soon called.

Nash Buckingham was one of the great duck-hunting writers of the period. H. Lea Lawrence relates in his 2001 GUN DIGEST article, The Saga of Bo Whoop, that in 1921 John Olin sent Buckingham his personal heavy double, a custom-choked Super Fox, for testing. Olin included his new Super-X magnum 3-inch shells loaded with 1 3/8 ounces of shot. Buckingham’s tests led him to buy his own custom Super Fox, “Bo Whoop.” Bo Whoop patterned about 90% at 40 yards with specially bored barrels. Buckingham had a solid 60-yard duck gun and was on his way to becoming a legend. Buckingham recorded his adventures in some of the best hunting stories ever written. I offer the following example from What Rarer Day in Buckingham’s book De Shootinest Gent’man and Other Tales published in 1934.

We join Buckingham in his “ducking skiff” as he is poled through the bayou by Ab, his black guide. Buckingham is jump-shooting with his “big double gun”. It is first shooting light. “A smothered roar from around the corner! Ab steadies the boat. I pick them up through the interlacing covert, a bunch of suspicious mallards driving for safety. But they must pass our way to clear! I hunker down and blaze away. Two birds tumble all awry from among the leaders. My second blast bites off a dismayed climber. Pandemonium! The marsh is in riot! Alarm calls! The surge of zooming pinions [wings]! Teal, mallard, widgeon and sprig [pintail] hover singly and in bunches overhead. It is, somehow, not easy to avoid shoving shells wrong end first into one’s gun. But I manage to concentrate, find the combination, and center a pair of easy sprigs. I am tempted to stop off awhile and call. But the charm of idle jump-shooting is far too potent.”

Charles Askins, in an article entitled Long Range Shotguns in the January 1930 issue of the American Rifleman, concludes that a 12-gauge magnum with 1 3/8-ounces of shot, patterning 80% or better “is pretty reliable [on ducks] at 65 yards.” However, Askins goes on to say “I have never, personally, had a shotgun which would reach far enough.” Before the eight gauge was banned in 1918, Askins had a Greener eight-gauge double with 36-inch barrels weighing 13 pounds. His handload was a “.heavy load of Herco powder and 2 ounces of shot, either 2’s or 4’s. It would stop ducks consistently at 80 yards.” Two years after Askins wrote the above, he received from Ithaca the first 3 1/2inch Magnum 10 double off the assembly line. Charles Askins is the father of the late Colonel Charles Askins, Jr., of course.

Such were the men of the long-range duck-hunting cult. Their attitude is summed up by Elmer Keith in Shotguns by Keith: “the satisfaction of seeing big ducks crumple at long range and come down and bounce on the ground or splash high in the water is the cream of shotgun shooting.”

It is my view that the long-range duck-hunting cult was a legacy from the days of market hunting. Bob Hinman, in his 1972 GUN DIGEST article Ten Cents a Duck, notes that “Shooting for the market was at one time a way of life for thousands of America’s skilled shotgunners.”

Market hunting was legislated out of existence in the late teens. However, killing ducks at long range remained the objective of many duck hunters. The 12-gauge 3-inch magnum shotshell was developed to achieve this objective.

The 1 5/8-ounce load of the mid-’30s bought the 12 magnum a few more yards of range. Elmer Keith instructs:”For the man who wants greater range and a bigger shot load for duck or goose shooting, the Model 12 Winchester is in a class by itself [with] the long 3” load.” Nevertheless, the 1 7/8-ounce load appeared in the mid-’50s and now a full two ounces of shot can be had in the 12 magnum. Askins and Buckingham would sure be surprised at how far the 12 magnum has come.

Shooting the Model 12 Duck Gun

I own two Model 12 duck guns. Although acquired many years apart, the two duck guns are of nearly the same vintages, 1952 and 1953. The first thing you notice when you pick up a duck gun is its weight and solid feel. No other pump shotgun feels like the duck gun. The extra weight is meant to soak up the recoil of what once was thought to be a very hard-kicking load. It still is. Twelve magnum guns grew lighter over the years and consequently kick harder. The near nine-pound Model 12 duck gun is an anachronism among today’s waterfowl hunting shotguns. However, the Model 12 duck gun should still be an excellent long-range waterfowl shotgun with the right ammunition. I have often wondered how well my guns would pattern with modern ammunition.

The duck gun made in 1952 has a Simmons ventilated rib. Winchester installed Simmons ribs and Simmons-designed ventilated ribs for several years. However, Winchester’s ribs were not marked with the Simmons name and Kansas City address as mine is. Also, the rib and its receiver extension cover the Winchester proof marks, a sure sign that it is not factory installed. My 1953 duck gun has the factory solid rib. Both guns have 30-inch Full choke barrels inscribed “FOR SUPER SPEED & SUPER-X 3 IN.” The bores are bright with no pitting. The takedown joints are tight (See the instructions in Madis’ book if your Model 12 has a loose take-down joint). The locked breech bolts of both guns have little perceptible play when the rear of the bolt is pressed from the side. This test determines if excessive peening of the bolt locking cut in the receiver has occurred. Loose bolts and excess head-space occur only after long service. This test, along with a check of adjustment remaining in the takedown joint and functioning of the slide lock dis-connector, are my standard mechanical checks for a Model 12. The solid rib gun shows carrying wear while the ventilated rib gun was refinished when the rib was installed. Both guns were disassembled, cleaned and lightly oiled before testing.

I decided to test the patterning of the five loads detailed in the accompanying table. Emphasis was placed on loads of #4 shot because of its historical significance in waterfowl hunting and association with the long-range objectives of the Model 12 duck gun. I included tungsten polymer shot because it is non-toxic to waterfowl and has the same density as lead. Also, it was the only 1 3/8-ounce magnum load available. I included #2 shot because this size shot has always been my goose and turkey load in 3-inch shells. The trap load was included because trap shooting is suited to the duck gun.

It is general consensus that 10 patterns are required for an accurate appraisal of a given load and barrel combination. I fired 10 patterns for each of the five test loads in each of the two duck guns, for a total of 100 patterns. Range was 40 yards from gun muzzle to target frame. Patterns were fired from a benchrest, using American Target Company B21 silhouette targets measuring 35 by 45 inches. The silhouette provides a precise aiming point. Each fired target was turned over and a 30-inch cardboard disc placed to cover the maximum number for pellet holes. The perimeter of the disc was then marked and the enclosed pellet holes counted. The number of pellet holes was divided by the average number of pellets in the load to produce the pattern percentage. Both shotguns shot to point of aim and all patterns were contained on the target paper due to precise aiming, facilitated by placing a 25-pound sack of lead shot between me and the gun butt.

Results and Discussion

The paired pattern percentages fired by the two duck guns with each of the five loads were not significantly different, judging by the overlapping standard deviations. Both guns averaged 80% or better patterns with all loads of #4 shot. Not shown in the table of results are the dense centers of patterns obtained with #4 shot compared to # 8 and #2 shot. Some patterns of #4 shot might let a duck escape if it were caught just inside the margin of the 30-inch circle. On the other hand, a duck caught in the middle of one of these dense-centered pattern sat 40 yards would receive a dozen or more pellets. Number 8 and 2 shot provided wider and more even patterns with no center thickening. Pattern percentages were around 70% with these latter loads.

Askins stated in Modern Shotguns and Loads: “All shotguns which are intended for long range work.should be patterned at 60 yards.” Continuing, “loads which pattern around 85% [at 40 yards] have that quality which will permit them to continue a pattern on down the range.”Askins found that each yard of range beyond 40 yards reduced pattern density by an average of two percent. Curious, I fired five additional patterns at 60 yards with Model 12 number 1418XXX and the Winchester load of 1 5/8-ounces of #4 shot. This combination, which averaged 83.6% at 40 yards, averaged 44.2% at 60 yards! Askins’ rule of thumb of 70 years ago still pertains with modern lead-shot ammunition.

Madis states “Winchester spent a great deal of time and effort to develop better chokes.” Furthermore, “Winchester constantly experimented, searching for improvements in all chokes, even the old standby full choke.” Winchester almost certainly would have perfected their Full-choke Model 12 duck gun to maximize patterns with #4 lead shot, the size most mentioned for long-range duck shooting in publications prior to the advent of non-toxic shot.

Winchester suggests their 3-inch 12-gauge shotshells with 1 3/8-ounces or 1 5/8-ounces of #4 shot for wildfowl hunting in their 1951 Ammunition Handbook: “These shells were developed especially for extremes in long range shooting with 12-gauge Winchester Model 12 and Model 21 Heavy Duck Guns.”

Charles Askins provides data for the patterning of several of his personal shotguns with Western’s Super X shells loaded with their new #4 copper-plated shot. Writing in the March 1927 issue of the American Rifleman, Askins reports that his Remington Model 10 12-gauge pump averaged 89% of 1 1/4-ounces of shot in a 3-inch circle at 40 yards. His Super Fox 12 gauge magnum double averaged 83.7% (two-barrel average) of 1 3/8ounces of shot under the same conditions. Askins’ Ithaca 10-gauge double with 2 7/8-inch chambers averaged 86.9% with 1 5/8-ounces of shot. His shotguns were undoubtedly the best long-range duck guns he found in extensive testing. Askins concludes “How far are we going to be able to kill ducks? Probably a lot farther than we can hit ‘em. A lot of us will have to begin learning to hit long-range ducks.” Sounds like an invitation to join the long-range duck hunting cult!

Keith stated in 1967: “The old 70% standard is now obsolete and most any full choke gun will go 75% or better. Some will even go 85% to 90%, but rarely.” Keith, who obtained Askins’ Ithaca 10 magnum double upon Askins’ death, achieved 93% patterns with two ounces of copper-plated#3 shot in the big double. This was after extensive reworking of the chokes by Ithaca.

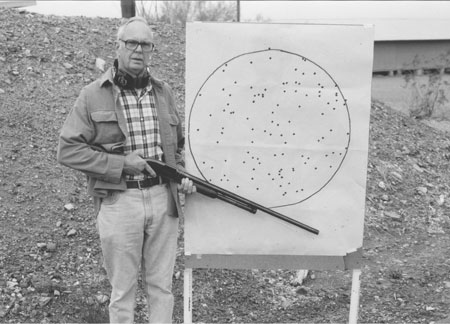

Model 12 duck guns are highly specialized tools for a very limited number of duck hunters who can regularly center a duck at 40-60 yards, and need to. That is why I have never used one of my duck guns for duck hunting. The ducks shot by me in the accompanying photograph were taken with Skeet boring and trap loads of #7 1/2-shot. My wife shot her share of ducks with a 20-gauge autoloader bored Improved Cylinder shooting one ounce of #7 1/2-shot. We limited our shooting to 25 yards or less and seldom missed. In those good old days of the 1960s the ducks flew just above the cattails and shots were plentiful. There was no need to shoot ducks at 60 yards.

Will Winchester ever build the Model 12 again? “No.” says Madis. “The nearest thing to a Model Twelve that could appear, whether domestic or foreign, would be a shotgun with the same model designation, but it would not and could not be a Model Twelve.” Browning, in fact, did import foreign-made copies of the Model 12 after Madis wrote the above. As good as the Brownings are, I’ll just keep my Model 12s from New Haven. The Model 12 duck guns are still as suitable for “waterfowl passes, fox trails or the habitat of the wary gobbler” as they were when the duck hunters at Winchester surprised the market in 1935.

Next Step: Get your FREE Printable Target Pack

Enhance your shooting precision with our 62 MOA Targets, perfect for rifles and handguns. Crafted in collaboration with Storm Tactical for accuracy and versatility.

Subscribe to the Gun Digest email newsletter and get your downloadable target pack sent straight to your inbox. Stay updated with the latest firearms info in the industry.

![Best Concealed Carry Guns In 2025 [Field Tested] Wilson Combat EDC X9S 1](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Wilson-Combat-EDC-X9S-1-324x160.jpg)

![Best 9mm Carbine: Affordable PCCs [Tested] Ruger Carbine Shooting](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Ruger-Carbine-Shooting-100x70.jpg)

![Best AR-15: Top Options Available Today [Field Tested] Harrington and Richardson PSA XM177E2 feature](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Harrington-and-Richardson-PSA-XM177E2-feature-100x70.jpg)