While also in the business of producing fine single stacks, STI makes a hybrid polymer-steel 1911 that takes hi-cap mags. There is no such thing as a “basic” STI.

STI is known for hi-caps and competition guns, However, that wasn’t always the case. A few years ago STI bought a local (Texas) company that was doing good work in making single-stack 1911s. And after that, STI went for the basic-gun market with another program. (More in just a bit.)

The basic STI hi-cap is the unchanged (except for even better quality) metal/polymer hybrid back in the early 1990s that we’ve already discussed. Dave Skinner and his wife have worked hard to promote the practical shooting sports and provide top-notch pistols for those competitors. Like other modern and savvy entrepreneurs, he is more than willing to take a chance on a particular model or set of features that looks promising. That, combined with the nearly genetically-based need to modify and experiment with gear, means that it can sometimes be difficult to find a “standard” STI at a match or on the range. Between Dave’s changes and the owner’s mods, what you’re looking at may be entirely different than the previous STI you just looked at.

The STI single stacks made here in the USA comprise most of the lineup. The Lawman, Sentry, Targetmaster and Rangemaster are just some of them, and they all feature forged steel frames, machined here in the USA (Texas, to be precise) and assembled with STI components. In addition to slides and frames, STI makes their own barrels, internals, grip safeties, etc. The basic gun by STI, the Spartan (and you have to figure, with Dave’s sense of humor, that the name is not an accident) is a no-nonsense gun at the lowest cost at which STI can deliver their quality.

It has a Philippines-made slide, frame and barrel that is assembled and fitted in the US by STI, using STI internals. You get a super-tough gun at a reasonable price, with STI quality. You do, however, give up some things: choices. You can have it the way it is, no extras, no options, no add-ons.

Unless, of course, you go to the STI custom shop, where they will build whatever you want, the way you want it, on an STI gun.

The moniker we all know for the modular frame is STI. (At least until we get to the famous “divorce.”) The Para and the STI had magazine tubes that were proportioned for .45 ACP cartridges. That meant a fatter frame, to hold the fatter magazine tube. The .38 Super magazines were the same tubes, but with ribs crimped into them to reduce the interior size, and allow for proper stacking of the smaller .38 Super. Caspian used magazines proportioned for 9mm/.38 Super that weren’t as wide as the magazines of Para or STI.

But as an all-steel frame, it was heavier than the STI. The STI weighed half what the Para and Caspian did, and so it saved the weight, which meant a red-dot sight and mount didn’t make your handgun into an anvil. It didn’t hurt that since the STI frames were CNC machined, and thus everything was straight and where it was supposed to be, it was a snap to drill and tap an STI frame for a scope mount. Later, the makers offered the drilling and tapping for you, as much to save them the hassle of dealing with mis-drilled holes and customer “fixes” of same as for any other reason.

The rocket-like interest in the .40 S&W cartridge also weighed in.

The membership of the USPSA at this time was like a dysfunctional family: everyone in their faction was in competition against everyone else and theirs. And everyone wanted things to fall out a certain way: their way. The Open shooters wanted Open guns in matches designed for their guns. The stock shooters wanted no comps or dots but beyond that couldn’t agree. There were those who wanted the “old days” of single stack 1911s, and everyone agreed that there had to be a place for the “wondernines” to shoot but couldn’t agree on how to accommodate them.

This was when there was some fracturing of competition. IDPA split off, the organizers being disgusted at how far from “reality” IPSC competition had gotten. The Single Stack Society formed, to give an outlet for the guns of yore to shoot. The IDPA quickly siphoned off a cadre of shooters. The Single Stack Classic, the match the Single Stack Society organized each year, was populated mostly by the shooters who had begun with the single stack 1911.

However, the USPSA took note. Soon, there were a host of Divisions in which you could shoot: Open, Limited, Production and Revolver (although that last one took longer). In Limited, which allowed almost everything except comps and dots, shooters soon figured there was no point in shooting a .45. You see, with a magazine limit of 140mm (Open allowed 170mm) the .40 offered greater capacity than .45 did. And since capacity was king in “hoser” stages, no-one wanted to be caught at a disadvantage. The change was swift and almost universal.

Things were settling down when politics reared its ugly head. In 1994, Congress passed, and President Clinton signed, the Assault Weapons Ban. Actually, the law was titled “Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994,” subtitled “Public Safety and Recreational Firearms Use Protection Act” and it did a whole bunch of pie-in-the-sky things. Among them was prohibiting the manufacture of magazines that held more than ten rounds. Existing magazines could be owned, used, sold, traded and repaired (more on that last part in a bit) but there could be no new ones, except those sold to law enforcement.

The reaction was swift: every magazine in the supply chain was bought, at dizzily-escalating prices. For a while, a hi-cap Glock 17 magazine could go for $150. The makers, knowing that screwing around would get them fined, imprisoned and/or ruined, made ten-shot magazines which were impossible to alter to hi-cap.

It quickly became apparent there would be a two-tier system if the USPSA didn’t do something: those with hi-caps and those without. So a new Division was formed: Limited Ten. For a while it looked like this would be the home of the single stack, but it proved not to be. So in due time (ten years later) the USPSA formed the Single Stack Division, giving the 1911 a place to play on a level field. There was also talk of an Open Ten, but it never materialized as an equipment Division.

The AWB/94 caused a whole lot of other changes. For one, it heightened interest in all the guns and gear that were “banned.” Also, it caused the Democratic Congress to be thrown out nearly en masse and turned the House of Representatives over to the Republicans. The law, thankfully, had a “sunset” provision in it: it would expire in ten years, unless it was voted to be renewed. It also allowed existing magazines to be repaired. To those in the know, this was a loophole big enough to drive an entire industry through.

You see, the law had no provision for marking “repaired” magazines, or tracking repairs, or anything. Other than saying they could be repaired, the law was silent. So, shooters quickly became adept at buying “repair” tubes from one source, and springs, followers and baseplates from another. Federal felony? Probably. Anyone prosecuted? Not a clue. Need to hide the fact now? Not in the least, unless it makes the anti-gun legislators wise up.

Trying to prosecute someone today (or even the day after the law sunset) for “manufacturing” hi-cap mags is like saying in 1934, after the Volstead Act has been eliminated, that you were going to be prosecuted as a bootlegger. As long as that was all you did, there was no longer a statute under which you could be charged. To charge someone now, for assembling magazines in, say, 2002, is as much a non-starter as charging your great-grand-dad for making bathtub gin.

However, Caspian did not wish to enter into the gray area of magazine repairs. They had a sale of their assembled tubes in the Fall of 1994 (I was there, at the USPSA Nationals. They had crates and cartons of mags and tubes on the tables; buy them while they lasted) and once the tubes were gone, Caspian focused on the components business of the single stack trade.

The single-stack makers, seeing that the limit was just beyond them, offered ten-shot single stack magazines. Then and now they are reliable, sturdy magazines.

With the hi-capacity Para and STI frames on the market, shooters had a choice: should they build a gun that hundreds of gunsmiths could work on, or go with the CZ clones, then imported by European American Armory, with a couple of dozen ‘smiths to work on them? The shooters voted with their wallets, and soon the ranges were filled with hi-cap guns made in the Western hemisphere.

However, many, if not most, were 1911 derivatives. The Open guns were Para or STI in .38 Super with comps and dots. The Limited guns were Para or STI in .40. Brian Enos and some others still carried the banner for EAA, Brian shooting a Limited EAA in .40 until he retired. But the guns were just outnumbered. Limited Ten became the Para and STI with ten-shot-magazines playground. Yes, you could shoot a single stack with ten-round magazines, but it wasn’t competitive.

And not for the reason you’d think. Leading to a minor controversy some years later. When someone noticed that some of the top shooters were using .40s at the Single Stack Classic, (recently the USPSA Single Stack Nationals) they cried foul. The top dogs were obviously taking advantage. As if.

I talked to the top shooters, and if I were to take all their reactions, throw them into a text cuisinart, and pour it out, it would be something like this: “Pat, I’ve been shooting .40 Limited for so long, it’s all I have. I’m not sure I can find any .45 ammo in my loading room.” For many top shooters, it was easier to simply buy/build a .40 single stack than to get back into loading .45 ACP or laying in a supply of ammo. The reason the Limited Ten Division became an STI/SVI/Para playground was equipment: if you were shooting a hi-cap Open gun a lot, and you want to shoot in Limited, you shoot the same gun in .40 If you wish to shoot Limited Ten, your easiest way (and less practice in transition) was to use your Limited gun, downloaded.

In Production Division, the USPSA rulesmakers desired avoiding an “equipment race.” That is, the exact sort of thing I just described: people chasing scores by buying equipment, even when the equipment didn’t matter, something shooters had been complaining about for fifteen years at that point. So, the scoring was made simple: everything was Minor. Once you exceeded the threshold, it didn’t matter what you used. Also, to avoid capacity problems, they made everyone shoot “ten round magazines.” Oh, your magazine might hold more, but don’t load more. This was not entirely due to the AWB/94. A Glock 17 holds 17+1 rounds. A Ruger or S&W of the time held 15+1. Clearly, based on past experience, shooters would move to the higher-capacity gun, if capacity were allowed to enter into things.

To preclude that, they set the limit (and kept it after the AWB/94 sunset) below the lowest capacity 9mm pistol, which for the 1911 didn’t matter, because to be a Production-kosher gun, it had to be double action. Or at least, not “cocked and locked.”

Enter Para ordnance with their LDA, the light double action, a 1911 frame with a double action trigger in it. As long as you didn’t load more than ten rounds, it was a Production-approved gun.

Partly as a result of the AWB/94, the 1911 started getting a lot more interest. You see, in the background, there was movement to change the “carry” laws across the country. Before the state of Florida changed, in the late 1980s, most states were what has become to be called “may issue.” That is, you go to the local police, or whomever, and ask for a license to carry a concealed pistol. If you meet whatever requirements there were (which in some locales, were pretty onerous) you were issued a license.

You had to prove you met the qualifications to be issued a permit. In a lot of places, “qualified” meant you’d contributed enough to the re-election campaign of a politician with enough “pull.” In other places, it simply wasn’t going to happen without a lot of legal expenses. And in still others, it didn’t matter what the law said, you weren’t going to get a permit no matter whom you knew, paid, or were related to.

Florida started it, and soon there was movement across the country to change that to a “shall issue” condition. That is, you applied, and unless the police could find some reason to disqualify you (and they didn’t have many options) you were issued a license. Now, they had to prove you were in the “disqualified” category, which many felt was a much more equitable arrangement. And one less prone to political abuse.

As a result, more people started carrying and buying guns to carry. While this was going on, the AWB/94 precluded large magazine capacity. People figured “If I can only have ten, I want the ten biggest I can get.” That is, .45 ACP, and this brought the 1911 back into the mix.

The situation with Chip McCormick, Sandy Strayer and Virgil Tripp ultimately fell apart. In 1994, Sandy Strayer left and formed Strayer-Voigt, later to be named Infinity. Dave and Shirley Skinner joined STI, and over time eventually bought the whole company; by 1997 it was Dave and Shirley. Virgil Tripp left once Dave Skinner bought the whole shebang and went back to custom gun building, chrome plating, and design. And things just kept getting better.

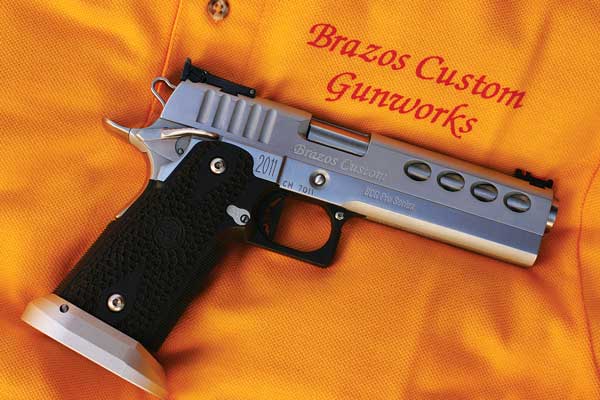

Dave Skinner at STI brought a volume attitude to production and marketing. He made semi-custom guns, semi-custom in that they were of a high quality, but you either ordered basic guns and had someone else trick them out or you got the “STI package” tricked-out gun. But do not make the mistake of thinking that STI guns were plain guns. Having a good number of CNC machining stations, STI could produce whatever they needed. And they could make them at the drop of a hat. So STI offered model after model. If it sold well, it stayed, if it didn’t, it became a collector’s item and got replaced by something with more promise.

Also, STI was willing to go out on a limb. For example, California is a strange state. As more than one wag has put it, “the country is tipped, and everything loose has rolled to the West Coast.” The California legislature is populated with firearms-ignorant do-gooders. One of the more inane laws they passed some years on handguns, to keep hitmen from using silencers. Being, as I said, ignorant of things firearm-ish, they didn’t write the law as “silencer threads” or “bare threads and a silencer” or anything like that. They wrote “no threads.” How do you attach a compensator to a barrel? Threads. How do you put a coned lockup on a barrel? Threads. So, your screwed-on-with-a-wrench, Loctite-ed, hand-fit compensator is verboten in California. Even if it is on so securely that you’ll need torches, a vise, wrenches and you end up destroying things in the process, you had an illegal firearm.

STI tried, with their Trubore barrel, to accommodate this inanity. The barrel and comp were manufactured as a single, integral unit. No threads. That wasn’t good enough. California decided they would be the arbiters of what was a “safe” firearm and so came up with a “test.”

The California test required a loaded (primed case, no bullet) handgun to be dropped on a steel plate, multiple times, while oriented in different directions. You’re probably asking “So what’s the big deal?” Simple: California didn’t foot the bill. You want the gun you manufacture approved, send them not one, not two, but three sample guns and a check to cover all the costs of testing. That’s right. You had to pay for the privilege of California destroying three of your finished product, and thus being approved.

It got even better. California is not so forgiving that if you make one basic gun, and a lot of derivatives, that getting the basic one approved includes the others. Nope. Change something and that “new” one needs approval, too. If you offer a dozen variants, that comes to 36 handguns, and a whopping big check to trash them all. Dave Skinner, bless his heart, finally just threw his hands up and said “[bleep] it.” He stopped selling guns in California, and told anyone who asked why.

For a while, Bar-Sto Precision, the barrel makers, manufactured a California-complaint STI. They could; they were based in Twenty-Nine Palms, California. The law only covered firearms being “imported” into California (as if California was its own country, with its own immigration, border patrol, customs and so on). However, the situation wouldn’t remain that way for long. The business climate in California became so onerous that like many other companies, Bar-Sto moved out. So there are a bunch of California owners who have collector’s items: Bar-Sto marked STI pistols.

After leaving, Sandy Strayer built the kind of company he wanted: a full-custom gun maker. Now run by his son Brandon, Infinity does not make standard items. Oh, they’ll show what they’ve done, and what other customers have had built, but you can’t order up “standard pistol number three” at Infinity. Instead, you use the web page, or fill out an order form, and you specify everything. Length, caliber, details like checkering pattern and spacing, grooves on top of the slide or not, frame color, size and type of safeties, etc. And it can get pretty wild, since the crew there is pretty imaginative.

If you want to have something that will be for a particular competition, be sure and let them know. They’ll tell you if the extras you’ve ordered will be USPSA, IPSC or IDPA-compliant, and in which Divisions.

This article is an excerpt from 1911: the First 100 Years.

Next Step: Get your FREE Printable Target Pack

Enhance your shooting precision with our 62 MOA Targets, perfect for rifles and handguns. Crafted in collaboration with Storm Tactical for accuracy and versatility.

Subscribe to the Gun Digest email newsletter and get your downloadable target pack sent straight to your inbox. Stay updated with the latest firearms info in the industry.

![Best Concealed Carry Guns In 2026 [Field Tested] Wilson Combat EDC X9S 1](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Wilson-Combat-EDC-X9S-1-324x160.jpg)

![Best 9mm Carbine: Affordable PCCs [Tested] Ruger Carbine Shooting](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Ruger-Carbine-Shooting-100x70.jpg)

![Best AR-15: Top Options Available Today [Field Tested] Harrington and Richardson PSA XM177E2 feature](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Harrington-and-Richardson-PSA-XM177E2-feature-100x70.jpg)