A review of the new .360 Buckhammer chambering and the Henry Model X lever-action rifle.

Lever-action rifles are among the oldest American repeating designs, and they’ve remained both a nostalgic and reliable choice for the past century and a half. Certainly, metallurgy has changed—undoubtedly for the better—and while the craftsmanship of run-of-the-mill guns might not present the artisan touch of the late 19th century, CNC machining and other modern advancements have resulted in a much more consistent product. We still have—in some form or another—those now-ancient names that became household words among hunters, including Winchester, Marlin and Savage, but modern companies such as Henry have also adopted the lever gun.

In addition to having many of the classic, late-19th and early 20th century rifle designs still with us, a good number of the cartridges of that era remain popular choices. With the .45-70 Government dating back to 1873, the .38-55 WCF dating to 1876, and the .30-30 Winchester coming onboard in 1895, there are a substantial number of venerable rifle cartridges that’ll still get the job done. If you hunt in an area where any rifle cartridge is acceptable, the world is your oyster.

But should you wish to use a centerfire rifle for big game hunting in certain Midwestern states, you’ll encounter a set of very particular game laws that vary from region to region.

Most require a straight-walled cartridge—one with no shoulder—in order to keep velocities on the lower side of the spectrum, and (presumably) prevent a high-velocity rifle bullet from skipping across the flat landscape. Others limit the case length, or specify a minimum bullet diameter. To comply with the rules and offer an advantage over the bigger, and often slower, straight-wall cases—like the .45-70 Government, .444 Marlin, .450 Bushmaster and .38-55 Winchester—ammunition companies have released some new designs. Winchester started with the .350 Legend, which is equally at home in a bolt gun or AR platform, and for 2023, Remington has countered with their own .360 Buckhammer.

A Chip Off The Ol’ Block?

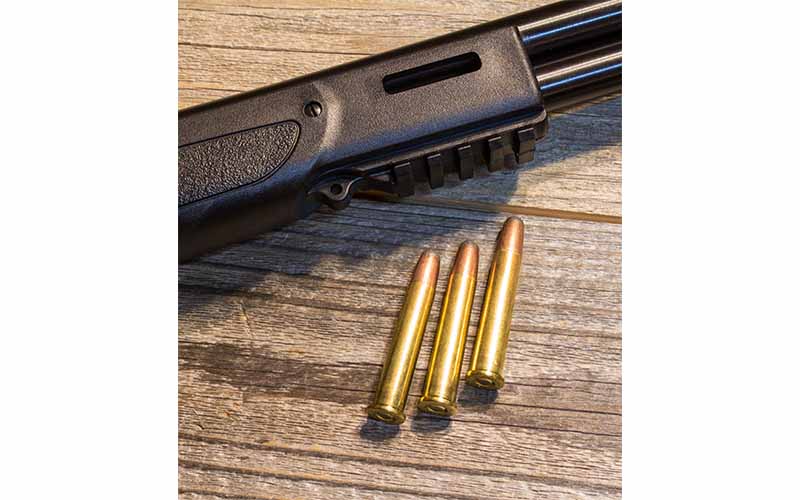

Based on the .30-30 Winchester case (derived from the older .38-55 Winchester) with the case walls straightened out, the .360 Buckhammer is, if you will, a twist in the idea of mating a .30-30 with a .35 Remington. It uses the same .506-inch rim diameter as its sire, but with a case length of 1.80 inches—shorter than both the .35 Remington and .30-30 Winchester. The maximum overall cartridge length is held to 2.5 inches, which is also just a wee bit shorter than the aforementioned pair.

With projectiles of 0.358-inch diameter, the .360 Buckhammer is offered in both 180- and 200-grain loads, featuring the time-tested Core-Lokt round-nose bullet. A simple cup-and-core bullet with a cannelure, or crimping groove, serves both to allow a good roll crimp to be applied to the case mouth as well as “locking” the core and jacket together. It’s a good deer bullet, especially when used at moderate velocities.

With the 180-grain load leaving the muzzle at 2,400 fps, and the 200-grain load moving at 2,200 fps, the .360 Buckhammer offers an appreciable velocity advantage over the .35 Remington, which usually moves that same pair of projectiles at 2,120 fps and 2,080 fps, respectively. Being round-nosed, these Core-Lokt bullets don’t have the best ballistic coefficient values, but the nose profile allows for safe use in the tubular magazines common to so many lever-action rifles.

Using a 1:12 twist, the .360 Buckhammer has the potential to offer the handloader the use of heavier bullets, though velocities will certainly drop off. But for those who enjoy taking a lever-action rifle to the thicker woods in pursuit of whitetails and black bears, the .360 Buckhammer is right at home.

Now, How To Launch It

Any new cartridge can be an exciting prospect, so long as you have a means to fire it. Many times, a cartridge will be introduced at SHOT Show, only to have the rifles for said cartridge be MIA for a year or more.

That’s not the case here with the .360 Buckhammer.

Enter Henry Rifles, who have worked in conjunction with Remington to bring four different models of their excellent rifles to market chambered for the Buckhammer, including their Lever Steel, Side Gate Lever Action, Single Shot Steel and the model I got to review, the Model X.

When I reach for a lever gun, I expect to see blued steel and walnut, or at least birch. I might even react calmly to stainless steel or a laminate wood stock, as in a Browning BLR. But a synthetic stock? Prior to holding the Henry Model X, I’d have declared it blasphemy; once I had it in hand, my opinion was swayed. Though the package will cause any lever purist to cock an eyebrow, the Model X is a serious hunting gun, packed with very usable and well-thought-out features.

With a receiver highly reminiscent of the hugely popular Marlin 336, the Henry Model X offers the advantage of a solid-top receiver and side eject, in that an optic can be mounted low to the bore. In lieu of a safety or half-cock, the Model X uses a transfer bar located in the face of the hammer. So long as the shooter keeps rearward pressure on the trigger, the transfer bar will make contact with the firing pin button—but if there’s no trigger pressure, or while the hammer is resting against the face of the receiver, there’s no chance of the rifle going off.

Using my Lyman Digital Trigger Scale, I measured the Model X’s trigger break at 3 pounds, 9 ounces, with almost no creep and just a bit of overtravel; for a lever gun, it was nice. Henry has equipped the Model X with a large lever loop, and I found that quite comfortable.

The 21⅜-inch barrel is topped with a fixed fiber-optic front sight, with a fully adjustable fiber-optic rear sight, and is threaded and capped to allow the user to install a brake or suppressor. The tubular magazine is accessible via the side gate lever on the right side of the receiver—just below the ejection port—or at the muzzle end, via a cutout in the magazine’s bottom that’s capped with an inner brass liner tube. The tube magazine has a five-round capacity.

Once I got past the initial doubts about the stock, it proved to be both comfortable and useful. It’s a two-piece affair, with a curved pistol grip, and textured patches on the pistol grip and forend that give a solid grip, even with wet hands. The buttstock has a solid rubber recoil pad—which I found to be on the harder side of things—and to my elation, it had a 14-inch length of pull. I’ve always appreciated the longer length of most European firearms, and this Henry is one of the first American production rifles I’ve come across with a proper stock length.

Instead of sling-swivel studs, normally screwed into the stock, Henry has opted to mold them into the stock, so there’s nothing to come loose, rust or squeak. The butt is symmetrical, having no cheekpiece, so the left-handed shooters will be equally comfortable with the Model X as the righties. The forend has a squared nose, with a short section of Picatinny rail on the underneath, and each of the sides features a Magpul M-Lok slot, so there are all sorts of options for attaching lights, bipods and other accouterments.

At Home On The Range

To prepare the Model X for the shooting range, I screwed a Leupold VX-3i 3.5-10x40mm scope—long proved a rugged choice and perfect for deer hunting in first and last light—in Talley detachable rings to the top of the X’s receiver. I chose the detachable Talleys in order to have a means of quickly accessing the iron sights. Should you want to use the Model X in truly thick terrain, yet have the ability of confidently reattaching the scope with a return to point of aim, this is your setup.

At my little 100-yard range behind my office, the Model X in 360 came alive. From the first shot, I noticed that the Henry rifle had very little felt recoil, even from the bench. The trigger broke nicely, allowing the crosshair to stay on target properly, and the minimal muzzle jump aided in reacquiring the target quickly.

Both the 180- and 200-grain load delivered sub-MOA accuracy—much better than I was expecting from a lever gun—with the 200-grain load printing just a bit better. The best of the three-shot groups hovered around the ½-MOA mark, the worst just under an inch, with the average just above ¾-MOA.

At any rate, the combination of Henry Model X and Remington .360 Buckhammer ammo is very inspiring. And while it might not be as flat shooting as a .308 Winchester or 6.8 Western, it makes a great woods rifle, with velocities slightly better than the comparable .35 Remington. My test rifle stayed very close to the advertised velocities, with the 180-grain load averaging 2,387 fps and the 200-grain load 2,208 fps.

During the bench session, each and every cartridge fed and extracted without issue; in fact, I found the out-of-the-box Henry to be much smoother than the majority of the modern Winchesters and Marlins I’ve spent time with. In spite of my initial apprehensions—solely based on my visual impression—I really enjoyed taking the Henry to the bench and wouldn’t hesitate to spend a season here in my native New York with this combination.

Where Does This Fit In?

Many will repeat the fact that the century-plus-old .35 Remington gives a similar performance, but that’s not entirely reason enough to discount the Buckhammer. Others will say that the venerable .30-30 Winchester is so plentiful and available that it makes no sense to deviate from that platform, or that if you wish to hunt with a cartridge larger than .30-caliber, the next logical step is the original straight-wall lever cartridge: the .38-55 Winchester. I feel slightly different, in that the .360 Buckhammer represents a higher-pressure variant of the classic formula.

Taking the niche game laws off the table, I think the .360 Buckhammer is a great cartridge for the hunter who stays inside of 150 or 175 yards, in pursuit of whitetail deer and black bears. It’s easy on the shoulder, available in four models of Henry rifles (proudly made in the USA) and hits harder than either the .30-30 or .35 Remington. I hope that the .360 Buckhammer gets the “modern spitzer” treatment that Hornady has given to so many of the classic rimmed cartridges and the same bonded-core treatment Federal applied to their HammerDown series. And, more rifles from various companies are likely on the way.

Long story short: I like the Buckhammer. Is it going to be my personal daily go-to? Probably not, as I’d classify myself as a bolt-action guy more than anything else, and my heart lies there. But for the lever crowd, I think this is a breath of fresh air and an awful lot of fun to shoot and hunt with.

Henry Lever Action X Model .360 Buckhammer Specs:

- Chambering: .360 Buckhammer

- Barrel: 21.375 Inches, 1:12 Twist

- Finish: Blued Steel

- Stock: Black Synthetic

- Length Of Pull: 14 Inches

- Overall Length: 40.375 Inches

- Capacity: 5 + 1

- Sights: Fiber Optic Front ; Adjustable Fiber Optic Rear

- Weight: 8.07 Pounds

- MSRP: $1,091

Editor's Note: This article originally appeared in the October 2023 issue of Gun Digest the Magazine.

Raise Your Lever-Gun IQ:

- The Henry .45-70 Gov't

- Evolution Of The Legendary Lever-Action

- Cowboy 101: How To Run A Lever-Action Rifle

- The Rossi Rio Bravo .22 Lever-Gun

- The Past, Present And Future Of Lever-Action Shotguns

Next Step: Get your FREE Printable Target Pack

Enhance your shooting precision with our 62 MOA Targets, perfect for rifles and handguns. Crafted in collaboration with Storm Tactical for accuracy and versatility.

Subscribe to the Gun Digest email newsletter and get your downloadable target pack sent straight to your inbox. Stay updated with the latest firearms info in the industry.

![Best Concealed Carry Guns In 2025 [Field Tested] Wilson Combat EDC X9S 1](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Wilson-Combat-EDC-X9S-1-324x160.jpg)

![Best 9mm Carbine: Affordable PCCs [Tested] Ruger Carbine Shooting](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Ruger-Carbine-Shooting-100x70.jpg)

![Best AR-15: Top Options Available Today [Field Tested] Harrington and Richardson PSA XM177E2 feature](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Harrington-and-Richardson-PSA-XM177E2-feature-100x70.jpg)

The butt end dirty looking. Shamefool for picture.