Whether it’s a Texas Ranger revolver or a warhorse rifle, each gun has a story to tell.

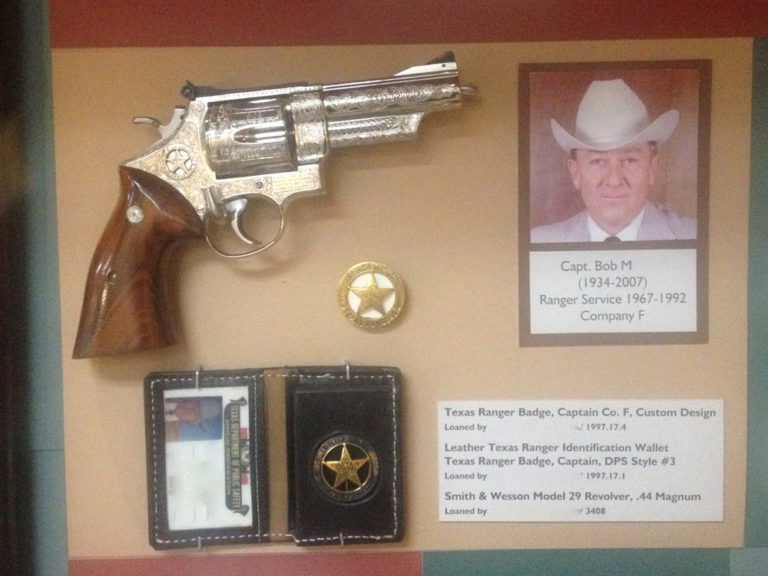

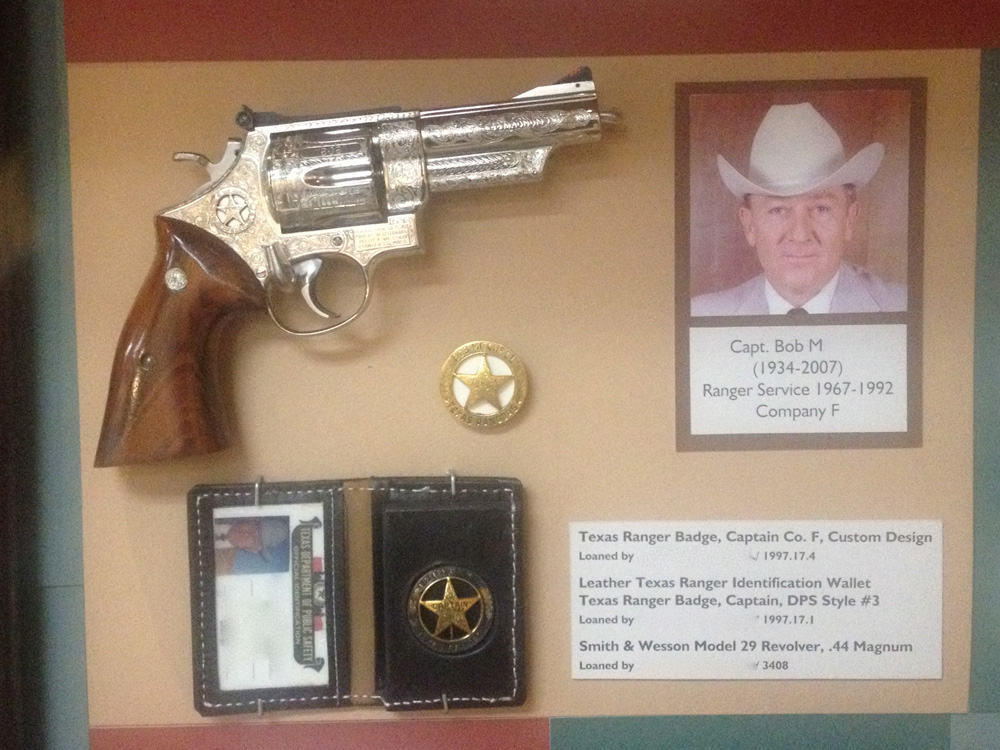

The citation next to the Smith & Wesson Model 29 in the display case said that Texas Ranger Bob M. had been carrying that particular pistol when he was called to the scene of a domestic disturbance. A man had been released from prison, and had promptly gone to the home of his estranged wife and taken her hostage at gunpoint. The police had the house surrounded when Ranger M. arrived, and the suspect was barricaded behind a couch in the living room.

All the cops, bristling with rifles, pistols and teargas guns, were hunkered down behind their patrol cars outside. Ranger M. calmly walked up to the porch and called inside to the suspect, telling him to put down his gun and come out with his hands up. The suspect called back with words to the effect that, if the Ranger wanted him, he was welcome to come in and get him.

So he did.

Ranger M. walked into the house, grabbed the culprit by the scruff of his neck, gave him a few whacks with the Model 29, dragged him out the door and handed him over to the local police. And then he went on about the rest of his work day.

The Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum, overlooking the banks of the Brazos River in Waco, Texas, still has that particular Smith & Wesson on display, along with hundreds of other guns and various equipment that officers carried during the famous law enforcement agency’s 191 years of existence. If those guns could talk, every one could tell stories of bravery, honor and adventure akin to the citation describing Ranger M.’s tale of unusual enforcement of the law.

The first time I saw the Model 29 in question, my friend had taken me to visit the museum, but first he said he wanted to show me a tractor he was working on. We drove to a small farm near Waco, looked at the tractor in the barn and visited with the owner, a friendly, ordinary-looking, retired gentleman.

Arriving at the museum, my friend pointed out the Model 29 in the display case, and told me to read the citation. When I had, he asked me what I thought. I said the fellow who had carried that gun must have been quite the hombre in his day. My friend said, “He was. That’s the man you met a while ago. He owns the place where my tractor is.”

In an age when America has been sissified and civilized and watered down almost beyond recognition, it’s good to know there are still brave men who aren’t afraid to do what it takes to get the job done. Most of the time they look like regular, ordinary folk, but when the time comes to make a stand, they step out and put themselves in harm’s way for the rest of us. To paraphrase John Wayne, they may be scared, but they saddle up anyway.

The guns carried by such men are similar to the men themselves. They’re not wimpy, delicate or fragile. They are tools, designed to fit a specific need and to hold up well under abuse and still function. They’re usually the best of their kind available during the times they’re employed, and are retired and replaced only when a better tool comes along for the job at hand. Their stories would fill libraries the world over, if written down.

The guns in the Texas Ranger Museum are some of the lucky few. Having seen their service, they’ve been offered a respite from their labors. Others, particularly surplus military guns, are often subjected to less auspicious fates. But their stories, if known, might be just as interesting.

Firearm History At The Local Gun Shop

The line of old Mausers had seen better days. There were about 20 of them in a rack at my local gun shop, in various stages of decay and neglect. Picked up en masse for a song, or even a verse or two, the price tags attested to the fact that these guns were no longer the proud warriors they’d once been. Any one of them was available for $125, as is, no guarantees, no sad songs and no returns.

Enjoying a Saturday morning at the shop with four friends, I made the owner a pitch—how about $75 apiece, provided all five of us bought one. The haggling settled at $100 each, with 100 rounds of 8-millimeter surplus ammo thrown in with each rifle. We all agreed and proceeded to coon-finger the guns, inspect bores and rub already well-rubbed stocks. One gent amused the rest by shouldering his choice and goose-stepping out the door.

The five of us convened at “the shooting bench,” a private range that belonged to a member of the group, and we spent the afternoon seeing what the old rifles could do. Some were more accurate than others, none was a tack driver, but all of them worked fine.

Mine was capable, we found, of putting three rounds into an 8-inch cactus pad at 300 yards, using the old flip-up ladder rear sight.

The World War II ammo we were using was less than optimal, however. Some of the rounds failed to fire, whereupon the shooter would hold still for a count of 10, and then open the bolt and fling the round away like a hot potato. After a while we decided we were pushing our luck, and fell to removing bolts and scraping old cosmoline from nooks and crannies.

All the stocks were scarred, pitted and abused from years of warfare, more so from decades of storage and mishandling. The wooden stocks probably told the story of those rifles better than anything else. They seemed to be the unsung heroes of a bygone era.

One stock had a group of notches carved into it, a testament, perhaps, to the marksmanship of a previous owner. Which war, and which side in that war, were left to the imagination.

Another, in perhaps a still more ominous vein, was adorned with a crude swastika. Whether the carver was actually a Nazi or just a fellow who wanted to make his rifle appear villainous we can never know.

Still, we all gathered round and got quiet when the offending symbol was pointed out.

All guns are new at one point, but unless they’re safe queens, they all see service of one kind or another, acquiring nicks, scrapes and abrasions throughout their lifetimes. Most firearms change hands several times, and rarely are their histories documented. But every gun tells a story. Where have your guns been?

This article appeared in the February 1, 2015 issue of Gun Digest the Magazine.

Next Step: Get your FREE Printable Target Pack

Enhance your shooting precision with our 62 MOA Targets, perfect for rifles and handguns. Crafted in collaboration with Storm Tactical for accuracy and versatility.

Subscribe to the Gun Digest email newsletter and get your downloadable target pack sent straight to your inbox. Stay updated with the latest firearms info in the industry.

![Best Concealed Carry Guns In 2025 [Field Tested] Wilson Combat EDC X9S 1](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Wilson-Combat-EDC-X9S-1-324x160.jpg)

![Best 9mm Carbine: Affordable PCCs [Tested] Ruger Carbine Shooting](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Ruger-Carbine-Shooting-100x70.jpg)

![Best AR-15: Top Options Available Today [Field Tested] Harrington and Richardson PSA XM177E2 feature](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Harrington-and-Richardson-PSA-XM177E2-feature-100x70.jpg)

A particular gun can always conjure up what may have happened to it, who may have handled it and where. Especially that old Colt single action or a S&W Schofield or even that old Merwin Hulbert .44.

I recently purchased an old Colt SA in .45 Colt that was a sad sight to see. I was interested in it for parts even though some were missing. Gripless old first generation only about 60% of the original nickel was remaining. Numbers all matched but some screws and mainspring was missing. It laid in a box for a few years without much thought. A friend was looking for a .45 barrel for an old SA he was repairing and I thought about that old Colt. Maybe that barrel would do for his project. I dug the old thing out and was looking it over. Yup, it was an old black powder frame and in better condition than I had remembered. A light went on! I noticed that it didn’t have an ejector rod housing and never did. No provision on the frame for one. I was holding a first generation black powder 4 inch Sheriff’s Model Colt SA.! Serial numbers said made in 1895. Off went a letter to Colt and a few weeks later a letter from Colt was in my hands. They confirmed it was genuine and made in February 1895. It was shipped to a company store at Lynx Creek Arizona Territory gold fields. It was custom ordered with one-piece checkered Elephant Ivory grips in nickel finish, number of guns in the shipment “one!” I spent over a year doing meticulous renovation of the Colt right down to the grips. Sure is pretty! Now I am digging into it past.