Admittedly, my cluttered loading bench has always been the haven for top-notch dies from Lyman, RCBS and Hornady, for both rifle and handgun cartridges.

That’s not a confession; it’s a statement of fact as well as confidence. My reloading dies from all three outfits have provided thousands of rounds for practice, competition and serious hunting in a variety of calibers. Most of my deer have been killed with reloads, and back in the days when I regularly participated in pistol matches at a local gun club, the only ammunition I ever used came off of my progressive RCBS press.

For straight-wall handgun cartridges, I strongly recommend carbide dies, as they cut down on reloading time and that makes for less work at the bench and more time at the range or out in the hills. The need for case lube is eliminated, and when a reloader really gets cranked up with a progressive press, it is possible to turn out scores of cartridges in an hour.

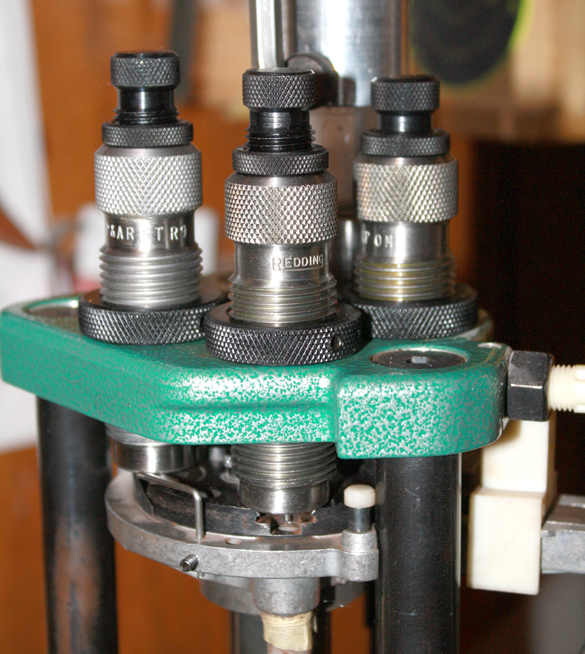

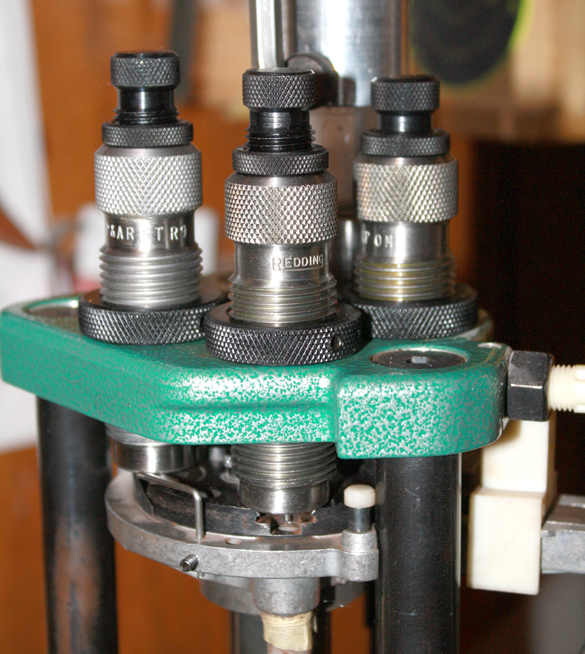

At the 2010 SHOT Show in Las Vegas, I encountered long-time pal Robin Sharpless, now with Redding Reloading Dies in Courtland, NY. A veteran in the firearms industry, Sharpless wasted no time in getting me to visit the Redding exhibit, where we engaged in a chat about reloading. And that’s when he introduced me to Redding’s titanium carbide dies.

“It’s a lot harder and slicker,” he commented, “and if you look at it under a super high power microscope, you would see (a surface) that looks like rolled river stones.”

Slick is great, and hard is even better when it comes to reloading dies through which thousands of cases will be resized. This was particularly intriguing to me since my younger son had recently acquired his own .45 ACP Sig Sauer P220, and while I love him dearly, I’ll be damned if I’m going to slave over a bench reloading ammunition for him to shoot up! (That said, he got the full course about how to set up new dies by raising the shell holder or plate to the top of its stroke, then running the new die bodies down through the press frame to “just meet” the shell plate, assuring full-length sizing, precise crimping and expansion of the neck.)

Redding, Sharpless explained, had come up with a nifty improvement in lock rings that features a tiny piece of soft lead between the front end of the retaining/tightening screw and the threads of the steel die body. This lead acts as a buffer to prevent damage to the threads, and one needs to give the ring a good rap where the tightening screw is located to free up the lock ring. Once it is tightened down again, the lead is right there doing its job.

Sharpless told me that Redding’s titanium carbide dies have been around for the better part of two decades, and that several commercial ammunition manufacturers use them in their operations. After setting up and running some rounds through them, I can understand why.

Alluding to my kid’s handgun purchase above, detailed in this space recently, was a subliminal reminder that good shooting, and especially good handgunning, comes from practice, and reloading cuts down on the cost of that endeavor considerably. Sure, there is the initial outlay for a press, dies, and components, but in the long run — and believe me, I’ve made that run along with countless other shooters — the reward is worth it, in money saved, in time afield and at the bench (all enjoyable), in accuracy and accomplishment, and in many cases, meat in the cooler. You simply cannot put a price tag on all of that; it’s a personal thing.

Redding’s dies are all hand-polished, and the titanium carbide rings are set into the steel dies just so. It’s hard to explain it in precise terms, but run a thousand rounds through a sizing die, and you’ll know the importance of that.

One thing I discovered upon opening the three boxes of sample dies Sharpless supplied for this review is that the gang in Courtland thinks of little details. All three boxes included a spare decapping pin, and if you’ve ever busted one of these off during a reloading session, you know just how important that might be.

Now, decapping pins — which ride down through the center of a cartridge case at the end of the steel rod inside the sizing die — are darned tough. Made from tempered steel, they are built to last, but they can break. I’ve broken one or two over the years (which says plenty about the amount of ammunition I’ve reloaded, not to mention my present age!) and it was a pain in the butt because I didn’t have an immediate replacement.

Another thing is the die box. Made from tough plastic, there are shell holders molded into the outer top and bottom that fit a variety of cartridge case heads. In my humble estimation, that is just plain darned clever. Who’da thunk it?

Now, with the addition of Reddings to my reloading dies, does that mean my other loading dies are going to be retired? Oh, not a chance! Something I learned from personal experience in loading .308 Winchester and .30-06 Springfield rifle cartridges is that one really ought to have two (or more) seating dies for every cartridge, one for seating bullets with crimping cannelures, and the other for taper-crimping non-cannelure projectiles.

For handgun cartridges, one seating die ought to be set up for seating nothing but ball or roundnose lead bullets, and another for seating jacketed bullets or semi-wadcutters, both with cannelures. Indeed, if one has three seating dies, each should be set up for different handgun projectiles.

What about my other carbide sizing dies? Are they now to gather dust? Ha! Fat chance of that. I’ve spent too many good years with them to simply set them aside. Nope, they got a good bath in Hoppe’s No. 9, a nice rub down with a soft cloth, a complete wash with degreaser, and they went right back to work.

I’m a tyrant…with a son’s pistol to feed.

This article appeared in the July 19, 2010 issue of Gun Digest the Magazine. Click here to learn more.

Resources for reloading:

Cartridges of the World, A Complete and Illustrated Reference for Over 1,500 Cartridges

Cartridges of the World, A Complete and Illustrated Reference for Over 1,500 Cartridges

The ABC's of Reloading, The Definitive Guide for Novice to Expert, 9th Edition

![Best Concealed Carry Guns In 2025 [Field Tested] Wilson Combat EDC X9S 1](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Wilson-Combat-EDC-X9S-1-324x160.jpg)

![Best 9mm Carbine: Affordable PCCs [Tested] Ruger Carbine Shooting](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Ruger-Carbine-Shooting-100x70.jpg)

![Best AR-15: Top Options Available Today [Field Tested] Harrington and Richardson PSA XM177E2 feature](https://gundigest.com/wp-content/uploads/Harrington-and-Richardson-PSA-XM177E2-feature-100x70.jpg)