Modern Gun School Special Content

By Jon R. Sundra

Choosing a riflescope today has never been easier … or more difficult with so many options.

In some ways today, matching a scope to a rifle is a no-brainer. I mean, all you need is a variable; you simply dial up an appropriate magnification for the job at hand. Simple.

And it’s even easier today because the zoom ratios on the newest generation of variable scopes can be as high as 1:6, meaning they can span magnification ranges of 1-6x, 2-12x, 3-18x and so on.

How can any hunting situation from varmints to big and even dangerous game not fall somewhere within those wide parameters?

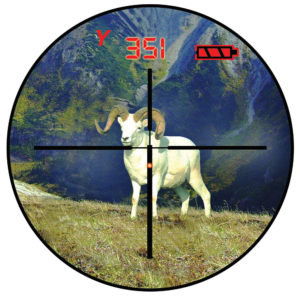

But then again, choosing the best match of scope to gun can be more frustrating than ever because there are so many features being offered today that didn’t exist a generation ago. We can now choose between 1-inch and 30mm body tubes; magnifying, non-magnifying and illuminated reticles; red dot sights; and ballistic compensating reticles calibrated to specific factory ammo or custom handload trajectories. There are even laser rangefinding scopes that compute distance to target and trajectory of the load being used, and then illuminate a spot on the bottom reticle arm indicating the proper hold point.

Rimfire Factors

That said, let’s start with the .22 LR. For a cartridge that’s running out of steam at 75 yards, what kind of a scope do you need? At that range a little fixed 4x scope will bring your 75-yard target to where it’s essentially 19 yards away.

With the more potent rimfires like the .22 WMR, .17 HMR and the new .17 Win. Super Mag, which can reach out to 150 yards or so, a 6x magnification is adequate for virtually any suitable rimfire target.

With the .22 centerfires, it’s a whole different story. If you’re primarily a predator hunter calling in fox, coyotes, bobcats, etc., you definitely need a mid-range variable. Depending on the calling set-up, you might have a shot at a critter coming in from a long ways off. On the other hand, if you’re well concealed and surrounded by cover, meaning close-in shooting, you’ll want a scope that can be cranked down to 1.5-2x.

For a rifle that will be used exclusively for long-range varminting—woodchucks, prairie rats, marmots, etc.—a fixed 12x or a variable that can match that magnification is a good place to start. For eastern woodchucks and western marmots I’ve always found 12x to be a good choice, certainly enough for these fairly large varmints that can weight up to 12 pounds.

For prairie rats I prefer a little more magnification, but 15-16x is about all I want. Some experienced shooters may disagree, saying that 20, 24 even 30x is perfectly usable, but I find the advantages of such high magnification come at too high a cost in other areas. Remember, as the power goes up, the size of the exit pupil, field of view and depth of focus all goes down. This applies to all scopes.

With prairie rats, for example, your targets are initially spotted with a binocular, then you must find them in the scope. The smaller the exit pupil and field of view, the harder it is to find in the scope what you were just looking at with the bino. Also, the smaller the field of view, the less likely it is to see where errant shots went. A .22-250 doesn’t recoil much—and a .223 less so—but they recoil enough that you usually can’t see where your misses are going. With a 25x scope, for example, your field of view is only 3.9 feet at 100 yards, 11.7 feet at 300 yards. A rifle doesn’t have to move much to momentarily put the target out of the field of view at recoil. And because the exit pupil is only 1.6mm, reacquiring that little shaft of light with your eye takes time. The larger the field of view—like the 13.1 feet at 100 yards you get with a 12x scope—the more likely you are to see your misses.

Big Game Optic Considerations

Choosing a scope for a game rifle is another matter entirely because there’s a lot more at stake. The more expensive and remote the hunt, the more critical overall quality and durability become in the type of optic you will use. For all-around nondangerous game, a typical mid-range variable can’t be beat. By “mid-range” I mean a scope that will go down to 2.5 or 3x, and up to 10 or 12x. Again, there will be those who disagree, but the way I see it, if a deer-size or larger animal isn’t big enough in a 12x scope, it’s too far away to be shooting!

If there is any distinction to be drawn concerning game riflescopes, it applies to dangerous game. For a rifle that will be used to hunt critters that bite back, the smallest, most compact low-range variables are the best choice. I’m talking short scopes with no objective bell. Most such scopes have a magnification range of 1.5-4.5x. Small, short, low-mounted scopes like these have little overhang beyond the support rings and are far less prone to being whacked out of zero by the careless handling that often occurs on safari when your guns are constantly being moved in and out of vehicles by trackers, skinners and camp staff. Keep in mind that 30mm body tubes are about 35 percent stronger than 1-inch tubes, but are not “brighter,” all other things being equal.

The fact that these scopes have a small objective lens doesn’t matter because when set at, say, 2x, the exit pupil diameter is a very large 10mm, which means that finding that shaft of light with your eye, upon shouldering the rifle, is instantaneous. And with a 10mm exit pupil, the scope is delivering all the light your eye can use, so you needn’t worry about less than optimum performance in low light. The same holds true even when set at 3x.

As far as reticles, are concerned, it’s pretty much a matter of choice. Experienced hunters usually rely on simple “Kentuck windage,” and guess at the amount of hold-over or hold-into needed on long shots. Younger generation hunters who have grown up with ballistic compensating reticles and are actually more likely to make such shots tend to rely on those features. In other words, they do work, but old timers like me find it hard to make the transition.

Illuminated reticles are becoming increasingly popular and well worth considering. I can recall an incident in Alaska a few years ago when an illuminated reticle made a shot on a bear possible. It was so dark that without it I would have never attempted the shot; it was just so dark that a conventional reticle would not have been visible.

Advances in optics continue at a feverish pace, and I can only wonder what the future holds. The one thing I am sure of, though, is that with optics, you get nuthin’ for nuthin’. To gain performance in one area, you give up something in another. That’s always been the case, and that’s the way it will always be.

This article appeared in Modern Shooter Spring 2015.